More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

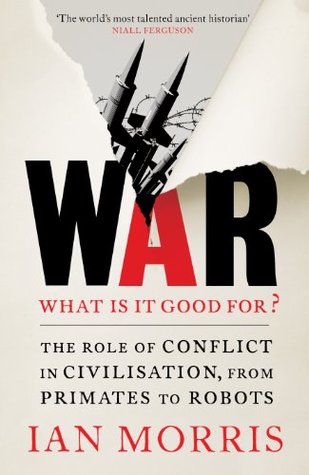

Ian Morris

You may not be very interested in war, Trotsky is supposed to have said, but war is very interested in you.

There are four parts to the case I will make. The first is that by fighting wars, people have created larger, more organized societies that have reduced the risk that their members will die violently.

By most estimates, 10 to 20 percent of all the people who lived in Stone Age societies died at the hands of other humans.

My second claim is that while war is the worst imaginable way to create larger, more peaceful societies, it is pretty much the only way humans have found.

People hardly ever give up their freedom, including their rights to kill and impoverish each other, unless forced to do so, and virtually the only force strong enough to bring this about has been defeat in war or fear that such a defeat is imminent.

My third conclusion, though, goes further still. As well as making people safer, I will suggest, the larger societies created by war have also—again, over the long run—made us richer.

War has produced bigger societies, ruled by stronger governments, which have imposed peace and created the preconditions for prosperity.

War, then, has been good for something—so good, in fact, that my fourth argument is that war is now putting itself out of business.

Basil Liddell Hart, one of the founding fathers of twentieth-century tank tactics, the bottom line is that “war is always a matter of doing evil in the hope that good may come of it.”

Out of war comes peace; out of loss, gain.

If you embrace the lesser evil, a little killing now might prevent a lot of killing later. The lesser evil makes for uncomfortable choices.

Keynes spent much of his career trying to finance Britain’s part in the world wars, but could still write in 1917 that “I work for a Government I despise for ends I think criminal.” He understood, perhaps better than most, that many governments are criminal.

In the long run, governments only survive if their rulers learn when to stop stealing, and even learn when to give a little back.

Leviathan is a racket, but it may still be the best game in town. Rulers in effect use force to keep the peace and then charge their subjects for the service.

The important thing about circumscription/caging, Carneiro and Mann argued, is that the people it traps find themselves forced—regardless of what they may think about the matter—to build larger and more organized societies. Unable to run away from enemies, they either create a more effective organization so they can fight back or are absorbed into the enemy’s more effective organization.

One chronicler describes how his fellows in the little town of Prato in northern Italy would nail a live cat to a post and then, with shaved scalps and hands tied behind their backs, compete to head-butt it to death, “to the sounds of trumpets.”

When the people of Mons in Belgium were short of something to do, they decided—having no criminals of their own on hand—to buy a robber from a neighboring town, tie a horse to each of his ankles and wrists, and then have him torn limb from limb. “At this,” we are told, “the people rejoiced more than if a new holy body had risen from the dead.” The only upsetting thing about the episode, said the chronicler, was that the good citizens of Mons paid too much for the man.

Between the Portuguese capture of Ceuta in 1415 and the era of “The Man Who Would Be King,” Europeans waged a Five Hundred Years’ War on the rest of the world.

There was a popular saying during the war that Britain provided the time, Russia provided the men, and America provided the money to defeat Hitler, but by November 1943, when Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt held their first group meeting, time was already on the Allies’ side. Only men and money now mattered, and Churchill found himself sidelined.

Soviets complained that their East German clients dragged them into crises they did not want, and the first secretary-general of NATO—the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, formed on a Norwegian initiative in 1949—joked that the alliance was a cynical western European conspiracy “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.”

Admittedly, students from Stanford University may be near one extreme of the nonviolent spectrum (psychologists call such people WEIRD—“Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic”), but even so they belong to a broader trend. We are living in a kinder, gentler age.

For many years, the U.S. government regularly published a pamphlet called the Defense Planning Guidance, summarizing its official position on grand strategy. Most Guidances were rather bland documents, but in February 1992, just two months after the Soviet Union dissolved, the committee charged with drafting a new Guidance did something outrageous. It told the truth.

What it drafted was a how-to guide for globocops. While the United States could not “assum[e] responsibility for righting every wrong,” it conceded, “we will retain the preeminent responsibility for addressing selectively those wrongs which threaten not only our interests, but those of our allies or friends, or which could seriously unsettle international relations.” This meant accomplishing one big thing: Our first objective is to prevent the reemergence of a new rival, either on the territory of the former Soviet Union or elsewhere, that poses a threat on the order of that posed formerly by

...more

In 2003, opinion pollsters found that only 12 percent of French and Germans thought that war was ever justified, as against 55 percent of Americans, and in 2006 respondents in Britain, France, and Spain even told pollsters that the warlike Americans were the greatest threat to world peace.

“On major strategic and international questions today,” the strategist Robert Kagan concluded, “Americans are from Mars and Europeans are from Venus.”

Europeans are from Venus because Americans are from Mars. Without the American globocop protecting the peace, Europe’s dovish strategy would be impossible. But on the other hand, without European dovishness, the United States could not afford to go on as globocop. If the European Union had acted more hawkishly over the past fifteen years, the costs of countering it would already be undermining the American position, just as the costs of countering Germany undermined the British globocop a hundred years ago. Mars and Venus need each other.

Menenius Agrippa, a prominent senator, entered the rebels’ camp to make peace. “Once upon a time,” Agrippa told them, “the parts of the human body did not all agree as they do now, but each had its own ideas.” The stomach, the other organs felt, did nothing all day but grow fat from their efforts, “and so,” Agrippa said, “they made a plot that the hand would not carry food to the mouth, nor would the mouth accept anything it was given, nor would the teeth chew. But while the angry organs tried to subdue the stomach, the whole body wasted away.” The rebels got the point.

Si vis pacem, said a famous Roman proverb, para bellum: If you want peace, prepare for war.

Hence the final paradox in this paradoxical tale: If we really want a world where war is good for absolutely nothing, we must recognize that war still has a part to play.