More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

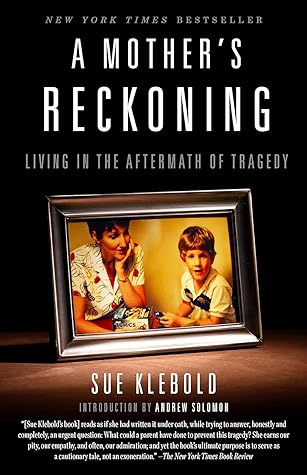

by

Sue Klebold

Read between

January 8 - March 7, 2024

I wish many things had been different, but, most of all, I wish I had known it was possible for everything to seem fine with my son when it was not.

There is perhaps no harder truth for a parent to bear, but it is one that no parent on earth knows better than I do, and it is this: love is not enough.

As a mother, this was the most difficult prayer I had ever spoken in the silence of my thoughts, but in that instant I knew the greatest mercy I could pray for was not my son’s safety, but for his death.

Instead, I felt a real sense of fear. I was afraid to make eye contact with God.

I hadn’t lost my faith. I was afraid to attract God’s attention, to further draw down His wrath.

One of the traits that marked Dylan throughout his life was an exaggerated reluctance to risk embarrassment, something that intensified as he entered adolescence.

I have since learned that perfectionism is frequently a characteristic of kids with special abilities. Ironically, it can sometimes undermine their potential. A mistake or setback that most kids would shrug off can devastate a child with unrealistic and unattainable standards. It can lower their self-esteem, causing them to disengage from the intellectual challenges that once fired them up.

How could I reach out, as a companion in sorrow, when my son—the person I had created and loved more than life—was the reason they were in agony? How do you say, “I’m sorry my child killed yours”?

The symptoms of intense grief—memory loss, attention deficit, emotional fragility, incapacitating fatigue—are surprisingly similar to those resulting from traumatic brain injury.

The theologian C. S. Lewis begins A Grief Observed, his beautiful meditation on the death of his wife, with these words: “No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear.”