More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

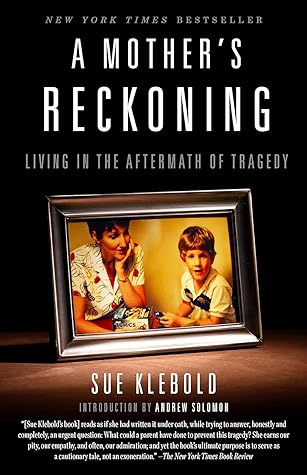

by

Sue Klebold

Read between

August 4 - August 9, 2025

To all who feel alone, hopeless, and desperate—even in the arms of those who love them

And must I, indeed, Pain, live with you All through my life?—sharing my fire, my bed, Sharing—oh, worst of all things!—the same head?— And, when I feed myself, feeding you, too? —Edna St. Vincent Millay

Sue told me at our first meeting about the moment on April 20, 1999, when she learned what was happening at Columbine High School. “While every other mother in Littleton was praying that her child was safe, I had to pray that mine would die before he hurt anyone else,” she said.

Yesterday, my life entered the most abhorrent nightmare anyone could possibly imagine. I can’t even write. —Journal entry, April 21, 1999

Dylan, wherever you are, I love and miss you. I’m struggling in the chaos you left behind. If there is any way to absolve you of these actions, please point the way. Help us find answers that will give us peace and help us live with this life we have been thrust into. Help us. —Journal entry, April 1999

The terror and total disbelief are overwhelming. The sorrow of losing my son, the shame of what he has done, the fear of the world’s hatred. There is no respite from the agony. —Journal entry, April 1999

Today, I began the task of writing condolence letters to the victims’ families. It was so hard. The tragic loss of all those children. It’s so hard, but it’s something I must do. From the heart of one mother to another. —Journal entry, May 1999

Read today that Mr. Rohrbough had destroyed Dylan and Eric’s crosses. I don’t blame him at all. No one should expect the grieving families of victims to embrace Dylan and Eric now. I’d feel the same way. —Journal entry, May 1999

Depression really kicked in when I read the Time Magazine article yesterday. They made Dylan sound human, like a nice kid gone astray. This hurts more than the villain portrayal because it shows how totally senseless it all was. He didn’t have to do any of this. He was so close to a life away from high school. If he was depressed, he didn’t show us.

Wandering around the house alone trying to function. —Journal entry, April 1999

In the early 1970s, I worked as an art therapist at a psychiatric hospital in Milwaukee. One day I overheard Betty, one of our patients with schizophrenia, say, “I’m just sick and tired of following my face around.” In the weeks and months after Columbine, Betty’s phrase came often to my mind.

I’m sick of waking up each day with a broken heart, of missing Dylan and wanting to scream loud enough to wake up from the nightmare my life has become. I want to hold Dylan in my arms again, to cuddle him as I did years ago, to hold him in my lap and help him with his shoes or a puzzle. I want to talk to him, and stop him from even considering this horrible act. —Journal entry, May 11, 1999

Tom’s words sound like a jackhammer to me, even those uttered most quietly. His thoughts are never aligned with mine. They always come from far away, and they’re totally foreign to my thinking.

I read mail for five hours, crying nearly the whole time. Two boxes now, one from the post office and one from the lawyer. So many cards and letters of love and support, and yet one hate letter and I am shattered. —Journal entry, May 1999

I’m tired of being strong. I can’t be strong any more. I can’t face or do anything. I’m lost in a deep chasm of sorrow. I have 17 phone messages and don’t have the energy to listen to them. Dylan’s room is just as the law enforcement people left it, and I can’t face putting it in order. —Journal entry, May 1999

This library had been a place for innocent children, a place where they should have been safe, and now they were all dead. —Journal entry, June 1999

Quote in the paper about cancer patients. It said “The people who do well create a place in their mind and their spirit where they are well, and they live from that place.” This is what we are doing. Tom’s analogy is that a tornado has destroyed our house, and we can only live in one part of it. This is what living with grief is like. You dwell in that small place where you can function. —Journal entry, August 1999

The theologian C. S. Lewis begins A Grief Observed, his beautiful meditation on the death of his wife, with these words: “No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear.”

Yesterday was terrible. After it took me 4½ hours to get up, the rest of the day wasn’t much better. I cried and cried and just couldn’t get it together. I talked to S. in the afternoon and told her I couldn’t go back to work, after I’d just told her I could. —Journal entry, May 1999

I was at work from 9–2:30 and made it through 4 meetings. I fought the whole time to look and act normal. I was slumped down and exhausted. By the end of the day I was beaten. I have huge, looming thoughts, and trying to get out normal words and thoughts and actions are like trying to push an elephant through the eye of a needle. No one can understand what I’ve been through or am going through. It’s all I can do to even attend or listen. When I got to my car after work, I shut the door and sobbed. —Journal entry, June 1999

Tom mostly wonders if we will ever be reunited with him. This is on Tom’s mind constantly. He says he’d feel comforted if he knew he’d see him again. I think a lot about where Dylan is and whether his evil actions prevent him from resting in peace, in God’s care. I hope there is a forgiving God who will recognize that he was a child. —Journal entry, May 1999

I sang sad songs and cried all the way to work. I could barely walk. I moved in slow motion. The words “Sometimes I feel like I’m almost gone” described how I felt. I got to work, sat at my desk and cried. I thought I might go home because I didn’t feel like working, then realized that home would be worse. Somehow, I eased into my work day and eventually the weight lifted and I began to concentrate on work. —Journal entry, August 1999

As I wrote in my journal, I’ve learned two important things. One, that there are many good, kind people out there. And two, there are many people who have suffered greatly and who keep going with strength and courage. These are the ones who can eventually support others. I hope I can be of use to someone some day. It would be a long road.

Right now all I want to do is die. Tom keeps saying he wishes he had never been born. Dylan was so loved, but he didn’t feel loved. I don’t think he loved anyone or anything. How did it happen? I didn’t know the boy I saw [on those tapes] today. My relationship with Dylan in my head and heart has changed. —Journal entry, October 1999

The meeting will take more courage than I can muster. I can only have my own little construct of what really happened until I speak with the investigators. I don’t want them to destroy the Dylan I am holding on to in my mind.

Today is really like the end of my life as I knew it before. If I learn horrible things tomorrow that I must carry with me from now on, I will look back on today and remember it as the end of a better time. We worked on our questions tonight. Byron gave me a long hug to help me face tomorrow. I hope tomorrow does not destroy the memory of the boy I loved. I don’t know what this video is they want us to see. —Journal entry, October 1999

One teacher, William “Dave” Sanders, was dead, along with twelve students: Cassie Bernall, Steven Curnow, Corey DePooter, Kelly Fleming, Matthew Kechter, Daniel Mauser, Daniel Rohrbough, Isaiah Shoels, Rachel Scott, John Tomlin, Lauren Townsend, and Kyle Velasquez. Twenty-four other students had been injured, three hurt as they tried to escape the school.

Once again, my life broke apart. If I hadn’t seen it I wouldn’t have believed it. My worst fears have come to pass. I keep thinking about his crazy rage and his intent to die. He lied to us and to his friends. He was so far removed from feeling. I keep trying to understand how that sweet, beloved child got there. I’m so furious with God for doing this to my son. —Journal entry, October 1999

Tufekci: “I can see no benefit whatsoever to releasing those tapes, only the possibility for great harm.” —Notes from a conversation with sociologist Zeynep Tufekci, February 2015

My relationship with Dylan in my head and heart has changed. I’m so angry with him right now. I wonder what I did as a Mom to make him feel so hurt, so angry, so disconnected. —Journal entry, October 1999

A friend once e-mailed me the following quotation, and it struck me as so apt that I dug up the book to read more: “Have patience with everything that remains unsolved in your heart,” Rainer Maria Rilke writes in his fourth letter to a young poet. “Try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books written in a foreign language. Do not now look for the answers. They cannot now be given to you because you could not live them. It is a question of experiencing everything. At present you need to live the question. Perhaps you will gradually, without even noticing it, find

...more

I came across an article on youth suicide prevention. In the first paragraph, the author said something like, “There is a temptation to look to outside influences like violent video games and lax gun control laws for an explanation of the tragedy at Columbine. But among all the other deaths and injuries, two boys died by suicide that day.”

Survivors often comment about how remote suicide seemed to them before they lost a loved one to it; the real question is why we persist in believing it’s rare, when it is really anything but. Someone in America dies by suicide every thirteen minutes—40,000 people a year. That is anything but insignificant.

Looking it up on 08/05/25, in the USA someone dies by suicide approximately every 11 minutes. That translates to around 132 suicide deaths per day. According to the CDC, over 49,400 people died by suicide in the USA in 2022.

Many of the researchers I have talked to believe that (barring chronic illness–related end-of-life decisions), suicidality is fundamentally incompatible with a healthy mind.

Dr. Victoria Arango is a clinical neurobiologist at Columbia who has dedicated her career to studying the biology of suicide. Her work has led her to believe that there exists a biological (and possibly genetic) vulnerability to suicide, without which a person is unlikely to make an attempt. She is currently working toward identifying specific changes in the brains of people who have died by suicide. “Suicide is a brain disease,” she told me.

Dr. Thomas Joiner, whose books are both meticulously researched as well as beautifully compassionate and personal, writes as both a psychologist and a survivor of his father’s suicide. His theory of suicide, a Venn diagram with three overlapping circles, has redefined the field. He proposes that the desire to die by suicide arises when people live with two psychological states simultaneously over a period of time: thwarted belongingness (“I am alone”) and perceived burdensomeness (“The world would be better off without me”). Those people are at imminent risk when they take steps to override

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I finally started to read some of his journal pages. He was expressing depressed and suicidal thoughts a full 2 years before his death. I couldn’t believe it. We had all that time to help him and didn’t. I read his writings and cried and cried. This was like the suicide note we never got. A sad, heart-wrenching day. —Journal entry, June 2001

I thought it might be helpful to have a distillation of a few points. 1. Nothing you did or didn’t do caused Dylan to do what he did. 2. You didn’t “fail to see” what Dylan was going through—he was profoundly secretive and deliberately hid his internal world not only from you, but from everyone else in his life. 3. By the end of his life, Dylan’s psychological functioning had deteriorated to the point that he was not in his right mind. 4. Despite his deterioration, his former self survived enough to spare at least four people during the attack. —E-mail from Dr. Peter Langman, February 9, 2015

This was one of the first things Dr. Peter Langman noticed. Dr. Langman, a psychologist, is an expert on school shooters and the author of a number of books, including Why Kids Kill: Inside the Minds of School Shooters.

Dr. Langman profiles in his recent book, School Shooters: Understanding High School, College, and Adult Perpetrators

Kay Redfield Jamison, in her masterful book about suicide, Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide

Definitive statement: “I do not think that Columbine would have happened without Eric.” —Note from a conversation with Dr. Frank Ochberg, January 2015

Crying too hard to take any more notes….I had made myself accept Dylan as a sadistic killer, but I had not yet come to grips with a Dylan who was trying to counteract his own “evil” with moments of goodness. I think I met this Dylan for the first time when Langman talked about it, so it gave me a different Dylan to grieve for.

Randazzo: “There is often a fine line between people who are suicidal and homicidal. Most suicides are not homicidal, but many who are homicidal are there because of suicidality.” I believe this is what happened to Dyl. —Annotated note from interview with Dr. Marisa Randazzo, February 2015

Dr. Adam Lankford, author of The Myth of Martyrdom

Dr. Dwayne Fuselier, a clinical psychologist and the supervisor in charge of the FBI team during the Columbine investigation, told me, “I believe Eric went to the school to kill people and didn’t care if he died, while Dylan wanted to die and didn’t care if others died as well.”

Four-hour lawyer appt was upsetting. The more we talked the more we saw how this “perfect” kid was not so perfect. By the time we were done we felt that our lives had not only been useless, but had been destructive….We wanted to believe that Dylan was perfect. We let ourselves accept that and really didn’t see signs of his own anger and frustration. I don’t know if I can ever live with myself. I have so much regret. —Journal entry, May 1999

Things have been really happy this summer….Dylan is yukking it up and having a great time with friends. —Journal entry, July 1997

Losses and other events—whether anticipated or actual—can lead to feelings of shame, humiliation, or despair and may serve as triggering events for suicidal behavior. Triggering events include losses, such as the breakup of a relationship or a death; academic failures; trouble with authorities, such as school suspensions or legal difficulties; bullying; or health problems. This is especially true for youth already vulnerable because of low self-esteem or a mental disorder, such as depression. Help is available and should be arranged. —American Association of Suicidology

A friend consoled me with the Winston Churchill chestnut: “If you’re going through hell, keep going.”