More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Snails weren’t pandas—those oversize bumbling toddlers that sucked up national conservation budgets—or any of the other charismatic megafauna, like orcas or gorillas. Snails weren’t huggy koala bears, which in reality were vicious and riddled with chlamydia. Nor were snails otters, which looked like plush toys made for mascots by aquariums, despite the fact that they lured dogs from beaches to drown and rape them.

On grant applications, before she self-funded through romance tours, Yeva wrote about the calcium cycle and the terrestrial mollusk’s pivotal role in regulating it. About turkeys that, during egg gestation, deliberately sought out snails like vitamin pills. About the role of gastropods in deadwood decomposition. How, due to their low mobility and sensitivity to environmental changes, gastropods served as barometers of a biome’s health. Birds and insects can fly, unwittingly lay eggs in outlying areas where their offspring can’t survive, but snails stay in place. It’s the snails that tell you

...more

Snails could’ve been useless, purely ornamental, and she’d still have scoured every leaf and grass blade for them. She could spend hours watching them in their terrariums, hours while her own mind slowed, slowed, emptied. When she lifted her eyes, the world seemed separate from her, a movie in comical fast motion, something she could turn off.

Her lofty long-ago conservation mission made her laugh now. Her new mission was whittled down to a simple checklist: Earn one more paycheck Procure one canister of hydrogen cyanide and a wedding dress for burial Climb into trailer, never wake up

Inevitably, with anyone she’d ever loved, the equation never changed: I have genitals. You have genitals. Let’s mash them together.

she did feel like she was going insane, enduring trial after trial, reconfiguring sex this way and that with the same result. Or nonresult. If, at the very least, the act repulsed her, repulsion was still a feeling, something she could work with, massage over and over in her hands until it warmed and mellowed, like plasticine, into desire.

For the past two years, after she’d stopped speaking to him, Yeva had traveled around the country with a reverse mission: instead of collecting snails, she restituted them.

She was in the middle of hooking up some newly bought hydrogen cyanide to the lab’s exterior hatch. There were simpler ways to go—she didn’t have to fill an entire trailer with noxious gas—but in her last act, why not allow herself a bit of flair? A bit of poetry? She’d die the way she’d lived, inside her trailer, her shell, like all those snails who’d died—were still dying, all around the world—curled inside theirs.

Sometimes, people on the street would shoot knowing glances at Nastia. Ah, it’s that kind of date. They’d spot the age difference, the telltale interpreter as third wheel. When the smiling foreigner opened his wallet, bystanders would often look at Nastia with judgment, disgust. It was women like Nastia who smeared the name of Ukrainians, the name of all women.

“And so a hundred men have to disappear, not just from our agency but from others, too,” the girl concluded after remembering to take a breath. “And not for money. Not for any explainable reason. It has to be senseless so it’ll scare off other foreign men from coming here, and the whole industry will collapse, not just in Ukraine but all over the world.”

Well, this was what growing up was all about. You had dreams, and you watched them get slowly whittled down. You had to learn to accept the hollowed remnants.

He says the material is really just hobbled nubs of narrative, barely connected; suggests that from “chapter” to “chapter” the protagonist reads like different people with ever-changing settings and supporting casts.

I’m getting calls for magazine interviews, photo shoots, radio appearances I’d only dreamed of when my book first came out. I’m trying to be grateful. But why must a country be bombed before we care about it?

coosimo кусаймо liked this

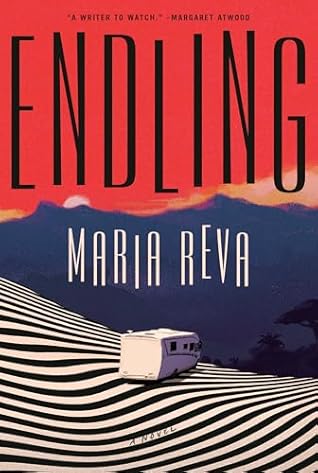

My novel-in-progress, Endling, explores the problematic practices that beset the international bridal industry, simultaneously interrogating the hackneyed, albeit persistently prevalent, Western perception of Ukrainian women as either docile and acquiescent “mail-order brides” or wily and deceitful scammers.

Now that Russia is conducting a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the central conflict woven into the delicate fabric of my novel, namely the influx of Western suitors into Ukraine, has been subjugated—or ripped apart, to keep with the metaphor—by a far more violent and destructive narrative. My novel (postnovel? yet-to-be defined entity?) needs further tailoring to reflect these rapidly changing circumstances. Returning to Ukraine and visiting cities like Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Kherson—the typical sites of romance tours—will enable me to restitch the novel to fit current times.

So long as the right few people are safe, you can move on with your life, right? Properly enjoy the oyster reception held in your honor as you speak on behalf of your bereaved motherland.

one might be tempted to focus on prior plans, no matter how irrelevant, rather than to accept, in the face of total chaos and unknowability, that there was no plan anymore, that everything had gone to shit, in the sense both narrow and broad.

The future had been a luxury. The future didn’t exist anymore.

Ukies have border collies; they are just like you. And, perhaps also just like you, they once thought disaster only befell other people.

I need to keep fact and fiction straight, but they keep blurring together.

Watching a war from abroad, rather than living it, can be its own brand of horror. Moonlike, we in the diaspora watch the captured zones of our homeland ebb and flow like tides. We are aware of every wave of bombings, first in piecemeal fashion from texts, phone calls, and social media, then aggregated into numbers (deaths, injuries, scope of destruction) on the news. Then we put on our shoes and go to work, surrounded by people who have other worries.

I wondered, uselessly, who had a proper claim to grief. I knew expats who mourned dutifully, refusing social engagements, their faces ashen as if Ukraine had already fallen. I also knew friends back in Ukraine who were hiding in basements and still hadn’t stopped cracking jokes.

When, in March 2023, my sister and I arrived in the country we’d watched burning from our phones, laptop screens, television monitors at gas stations, I wanted to be “resolved.” And there was certainly something satisfying about watching fellow Ukrainians resolutely going about their lives. What I felt, reuniting with my relatives, still leaves me speechless.