More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

nastasia, the girl called herself.

tried building a different novel-yurt before, that one set in Ukraine, its structure large and sprawling, more mansion-like than my other set of yurts, but the Russians began bombing it. What right do I have to write about the war from my armchair? And to keep writing about the mail-order bride industry seems even worse. Dredge up that cliché? In these times? Anyway, am I even a real Ukrainian? I left the country as a child. I speak more Russian than Ukrainian, and neither that well.

As previously discussed, we were hoping for your perspective as a Ukrainian expatriate watching the horror unfold from abroad (gentle emphasis on horror), i.e., how you and your family are feeling and how that emotional journey stands apart from the reporting/responses from non-Ukrainians. Could you resubmit by tomorrow a.m.?

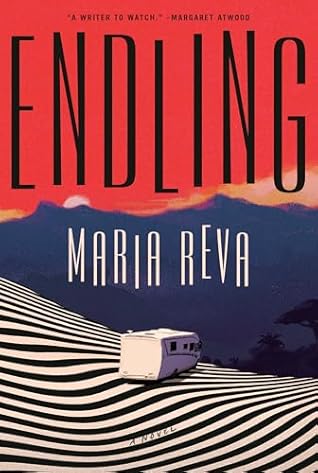

My novel-in-progress, Endling, explores the problematic practices that beset the international bridal industry, simultaneously interrogating the hackneyed, albeit persistently prevalent, Western perception of Ukrainian women as either docile and acquiescent “mail-order brides” or wily and deceitful scammers.

A Note on the Type This book, a novel, was set in Serifus Libris, a typeface designed by distinguished Italian engraver Giuseppe Pizzinini (1852–1913). Conceived as a private handkerchief embroidery type to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of his marriage to Countess Johanna Trauttmansdorff of Austria, and modernized before his untimely death by screw press, this type displays the tireless qualities of a master craftsman intent on weaving letter to letter, sentence to sentence, chapter to chapter, to create a sense of cohesion or an illusion thereof. In this way he shaped manifold

...more

What else? Loves analog, hates digital—parts you can’t see with your own eyes or fix with your own hands. Yet, in secret, he bought himself a computer and took a special tech course just so that he can turn the thing on, Sundays at 7:00 a.m. EET, to video-chat with us. Then promptly turns it off for the rest of the week. If we don’t sign in at the allotted time he’ll worry, but will turn off the computer anyway so as not to leave it running, much like you wouldn’t leave a drill or a blow-dryer running.

Yeva pulled a dented thermos from the cup holder in her door and said, “Here’s some bad coffee. Now it’s a committee meeting.”

Yeva took a deep breath and explained why Kherson, but Nastia could barely understand. Leave two girls and thirteen men alone in the dark, all for a glorified slug hundreds of miles away whose shell spiraled the wrong way? Or, the right way, apparently, for Yeva’s purposes. Nastia saw that she had misread Yeva, overestimated her moral compass. Or underestimated it? Nastia and Sol were only humans after all, two among billions, while that snail figured among a handful of its species. The snail was more valuable. Wasn’t that how these environmental fanatics thought?

“Is that a Tesla?” Sol asked, peering into the passenger-side mirror. “With a generator strapped to the roof?” Yeva leaned over Nastia to look. Her thick black waves brushed Nastia’s chin. “An electric car converted to diesel, that’s a first.”

“Sounds a lot like the novel my granddaughter’s been trying to cobble together. She mailed me a draft, fed through one of those internet translation machines. It’s about a girl who thinks she can get her activist mother back by kidnapping a bunch of men.” Put this way, the plan didn’t sound great to Nastia. “How does the book end?” “Turns out the mother just fell in love.” “Not very believable, an ending like that,” Nastia said. “Does she ever write or call the daughters she abandoned?”