More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Her professor backed up her hunch, on account of the irregularities at the Boot Hill site: all those fractures and cratered skulls, the rib cages riddled with buckshot. If the remains from the official cemetery were suspicious, what had befallen those in the unmarked burial ground?

Plenty of boys had talked of the secret graveyard before, but as it had ever been with Nickel, no one believed them until someone else said it.

for him to do nothing was to undermine his own dignity.

Further back, it was more gruesome. “When you graduated, you didn’t go back to your family, you had parole where they basically sold your monkey ass to people in town. Work like a slave, live in their basement or whatever. Beat you, kick you, feed you shit.” “Shit food, like we get now?” “Hell, no. Way worse.” You had to work off your debt, he said. Then they let you go.

The smell, she said, for one—of the rotting food and the bleach the supers sprayed on top of it. The bleach was for the flies that swarmed over the piles of trash in a gross haze and for the maggots twisting on the pavement. Then there was the smoke. People lit the garbage on fire to get rid of it—he didn’t understand this,

The fire of 1921 claimed twenty-three lives. Half the dormitory exits were bolted shut and the two boys in the dark third-floor cells were prevented from escaping.

he fooled himself that he had prevailed. That he had outwitted Nickel because he got along and kept out of trouble. In fact he had been ruined. He was like one of those Negroes Dr. King spoke of in his letter from jail, so complacent and sleepy after years of oppression that they had adjusted to it and learned to sleep in it as their only bed.

She was a survivor but the world took her in bites.

Throw us in jail, and we will still love you. Bomb our homes and threaten our children, and, as difficult as it is, we will still love you. Send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our communities after midnight hours, and drag us out onto some wayside road, and beat us and leave us half-dead, and we will still love you. But be ye assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer, and one day we will win our freedom.

After the Civil War, when a five-dollar fine for a Jim Crow charge—vagrancy, changing employers without permission, “bumptious contact,” what have you—swept black men and women up into the maw of debt labor,

The state outlawed dark cells and sweatboxes in juvenile facilities after World War II. It was a time of high-minded reform all over, even at Nickel. But the rooms waited, blank and still and airless.

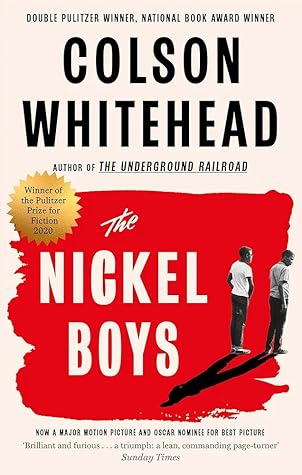

This book is fiction and all the characters are my own, but it was inspired by the story of the Dozier School for Boys in Marianna, Florida. I first heard of the place in the summer of 2014 and discovered Ben Montgomery’s exhaustive reporting in the Tampa Bay Times. Check out the newspaper’s archive for a firsthand look.

Officialwhitehouseboys.org is the website of Dozier survivors, and you can go there for the stories of former students in their own words.

Former prison warden Tom Murton wrote about the Arkansas prison system in his book with Joe Hyams called Accomplices to the Crime: The Arkansas Prison Scandal. It provides a ground’s-eye view of prison corruption and was the basis of the movie Brubaker, which you should see if you haven’t. Julianne