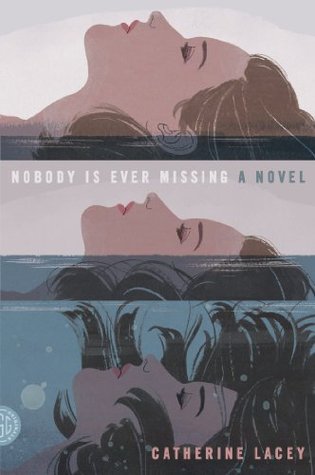

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

—John Berryman, “Dream Song 29

The poem is a glimpse into the mind of a terribly troubled man named Henry. He seems to be wracked with an inexorable sense of guilt and anxiety. Henry thinks he's committed murder, but he keeps desperately trying to recollect his memory and check over everyone in his life, and he always comes to with the same conclusion: he didn't actually kill anybody. But the cycle always starts again, and he can't escape this terrible feeling that he did.

Inside our laughing we weren’t really laughing.

I ordered a double bourbon even though I don’t usually drink like that and the bartender asked me where I was from and I said Germany for no good reason, or maybe just so he wouldn’t try to talk to me, or maybe because I needed to live in some other story for a half hour: I

They’ll still yell about laptops and liquids and gels and shoes, and no one will ask what’s wrong because everything is already wrong, and they won’t look twice at you because they’re only paid to look once.

The skin on my lips was drying and I thought about how all the cells on every body are on their way to a total lack of moisture and everyone alive has that thought all the time but almost no one says it and no one says it because they don’t really think that thought, they just have it, like they have toes, like most people have toes; and the knowledge that we’re all drying up is what presses the gas pedal in all the cars people drive away from where they are, which reminded me that I wasn’t going anywhere, and I noticed that many cars had passed but none had stopped or even slowed, and I began

...more

And I was here. And nothing had followed me—I was a human non sequitur—senseless and misplaced, a bad joke, a joke with no place to land.

days are a finite resource and it’s best to protect the ones you have.

This kind of day doesn’t want you to dare it, doesn’t want you to flip a coin, doesn’t want you to pick up a stranger off the side of the road.

Well, folks, there you have it, I said, but there were no folks.

I didn’t tell him, like I didn’t tell anyone, that Elyria was a town in Ohio that my mother had never visited. That was all my name meant: a place she’d never been.

He put his hand on my shoulder as if he was taking someone’s advice to do so and he let it stay there for a moment and after that moment water did come out of my eyes and I felt more appropriate and more human to myself.

Anytime two people can look at each other and talk honestly, that is God.

We looked at each other like Yeah, uh-huh, sure, and we ate cheese and crackers for dinner and watched that movie and we didn’t have to talk because we knew what the other was thinking—this was one of those you-don’t-have-to-say-it, I-suffer-like-you-suffer moments and our brains were calm and still, just lying there in our heads and our mother was also calm and still, just lying there in that box. All three of us, I thought, all three of us are orphans.

I didn’t have to feel any of those feelings anymore because I had left my husband and our arguments and my chef’s knife and I had come to this country where I could laugh, so gently, gently laugh at things that were actually not funny.

And he knew I meant his mother, that it was his turn to try to get near the loss that he couldn’t get away from, those thoughts that came back each autumn just to die for him again, to remind him of what had happened, of how it felt.

I knew what he’d say next, but I always listened intensely, as if I was trying to memorize his pain so I could re-create it once he was gone or dead or dead and gone, because I thought, at the time, that my husband’s loss was what I had really fallen in love with, and maybe that loss was locked up in my husband like a prison and this was our once-a-year meeting and so I had to press myself against the Plexiglas to feel the blood and body heat of his loss, stare hard at the loss so I could remember how its face was shaped, the exact color of its eyes, something to get me through the next year

...more

I knew it was possible that I was not in love with a person but a person-shaped hole.

I asked him questions like this even though it made my husband suffer, like a child pinching leaves off a fern frond.

What did it mean that she knew something that I would eventually know, that her dying made my life take this turn?

envied how simply those hands could be what they were—ambivalent chunks of bone and muscle that just touch, hold, and are held, repeat.

The amount of patience in this country—how long a person could spend happily waiting—maybe this was why I had come here. Not for the isolation, but the place where people can happily do very little, the world’s largest waiting room.

And I knew that it was possible he wasn’t entirely right for me, but I also knew, in some way, that probably no one was right for me and potentially no one was right for anyone, but I also felt, with uncharacteristic sincerity, that we were as right for each other as any two people could manage,

Mother said, Oh, I just don’t understand you and your moods, why you can’t just control yourself, or maybe she didn’t say anything right then, maybe she just got out a compact to look at and powder her nose and I knew that’s what she probably did after she wrote that one-line email, that everything okay? She probably looked into a mirror to make sure her nose was still sitting on her face as usual,

No one likes to be unrecognizable. No one wants to be a stranger to someone who is not a stranger to them.

being occasionally destroyed is, I think, a necessary part of the human experience.

Some people make us feel more human and some people make us feel less human and this is a fact as much as gravity is a fact and maybe there are ways to prove it, but the proof of it matters less than the existence of it—

And this went on for a while and I became a haver-of-authentic-emotions, an openhearted, well-adjusted, and thriving person, a dependable employee, a woman who could go out to a deli and order a sandwich and eat it and read the newspaper like a grown woman without thinking of the sentence I am being a grown woman, eating off a plate, and reading the news, because I was not an observer of myself, but a be-er of myself, a person who just was instead of a person who was almost.

there is a part of every human brain that just can’t bear and be, can’t sit up straight, can’t look you in the eye, can’t sit through time ticking, can’t eat a sandwich off a plate, can’t read the newspaper, can’t put on clothes and go somewhere, can’t be married, can’t keep looking at the same person every day and being looked at by the same person every day without wanting to make him swallow a tiny bomb and set that bomb off and make him disappear, go back in time and never get near this man who is looking at you and living with you and being so happy to just love and be loved and we all

...more

Isn’t everyone on the planet or at least everyone on the planet called me stuck between the two impulses of wanting to walk away like it never happened and wanting to be a good person in love, loving, being loved, making sense, just fine?

and to love someone is to know that one day you’ll have to watch them break unless you do first and to love someone means you will certainly lose that love to something slow like boredom or festering hate or something fast like a car wreck or a freak accident or flesh-eating bacteria—

I would like to go back to being or feeling redeemed by him,

I only had a few hundred dollars in checks because a false sense of having my shit together only cost a few hundred dollars.

I didn’t just want a divorce from my husband, but a divorce from everything, to divorce my own history;

He put down his glass, wiped his mouth, looked over his sleeve at me, and nodded a nothing nod, which was good because I didn’t want to deal with a something nod.

it’s odd that people go to the beach and stare at the waving water and feel relaxed because what they are looking at is just the blue curtain over a wild violence, lives eating lives, the unstoppable chew, and I wondered if any of those vacationing people feel all the blood rushing under the surface, and I wondered if the fleshy, dying underside of the ocean is what they’re really after as they stare—that ferocious pulse under all things placid.