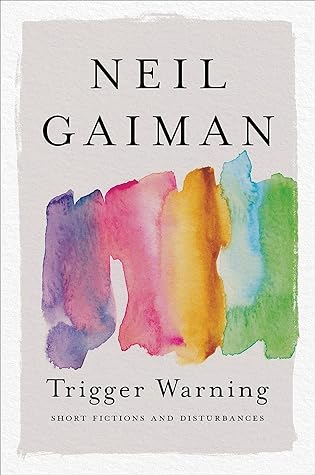

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Neil Gaiman

Read between

September 1, 2023 - July 1, 2024

She must do something, to keep body and soul from dissolving their partnership, but none of the folk of the dock have the foggiest idea what this could be.

“Sometimes I think that truth is a place. In my mind, it is like a city: there can be a hundred roads, a thousand paths, that will all take you, eventually, to the same place. It does not matter where you come from. If you walk toward the truth, you will reach it, whatever path you take.” Calum MacInnes looked down at me and said nothing. Then, “You are wrong. The truth is a cave in the black mountains. There is one way there, and one only, and that way is treacherous and hard, and if you choose the wrong path you will die alone, on the mountainside.”

I woke in the night. There was cold steel against my throat—the flat of the blade, not the edge. I said, “And why would you ever kill me in the night, Calum MacInnes? For our way is long, and our journey is not yet over.” He said, “I do not trust you, dwarf.” “It is not me you must trust,” I told him, “but those that I serve. And if you left with me but return without me, there are those who will know the name of Calum MacInnes, and cause it to be spoken in the shadows.”

I saw him in his dressing gown. I saw him knock upon her door. I saw it open. He went in. There’s nothing more to tell. My landlady was there at breakfast, bright and cheery. She said the dentist had left early, owing to a death in the family. She told the truth.

The day that my wife walked out on me, saying she needed to be alone and to have some time to think things over, on the first of July, when the sun beat down on the lake in the center of the town, when the corn in the meadows that surrounded my house was knee-high, when the first few rockets and firecrackers were let off by overenthusiastic children to startle us and to speckle the summer sky, I built an igloo out of books in my backyard.

I slept in my igloo made of books. I was getting hungry. I made a hole in the floor, lowered a fishing line and waited until something bit. I pulled it up: a fish made of books—green-covered vintage Penguin detective stories. I ate it raw, fearing a fire in my igloo.

I saw someone who looked like my wife out there on the ice. She was making a glacier of autobiographies. “I thought you left me,” I said to her. “I thought you left me alone.” She said nothing, and I realized she was only a shadow of a shadow.

I saw the shadows of the bears before I saw the bears themselves: huge they were, and pale, made of the pages of fierce books: poems ancient and modern prowled the ice floes in bear-shape, filled with words that could wound with their beauty.

And then I crawled out, and I lay on my back on the ice and stared up at the unexpected colors of the shimmering Northern Lights, and listened to the cracks and snaps of the distant ice as an iceberg of fairy tales calved from a glacier of books on mythology.

I remember my boots going. Or “being gone,” I should say, as I did not ever actually catch them in the act of leaving. Boots do not just “go.” Somebody “went” them.