More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

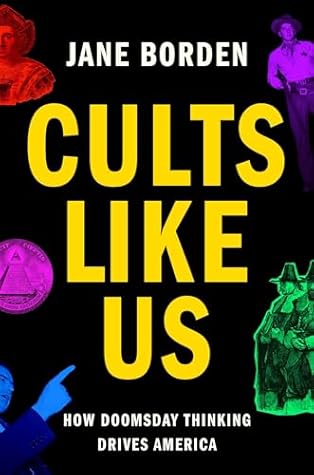

Jane Borden

Read between

March 26 - June 21, 2025

The Pilgrims and the Puritans—known in their time as radical Protestants or “hot” Protestants—were apocalypticists. They believed the end of the world was imminent. On this violent “day of doom,” the chosen few would be saved and their enemies punished.

Many of America’s persistent philosophies—including individual liberties, limited government, and the Second Amendment—follow this paradigm, presupposing an evil “them” attacking a chosen “us.” Why would Gadsden’s flag read “Don’t tread on me” unless he assumed someone trying to tread? America’s early religious refugees did not in turn practice tolerance. The Puritan colony quashed dissent with particular zeal, banning Catholics and hanging Quakers.

But beware: when someone claims others aim to steal from you, the thief is usually the one talking.

This meaning coalesced in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the work of Robert Jay Lifton, a psychologist, who pioneered studies of thought reform (a practice colloquially known, if somewhat inaccurately, as brainwashing). In a 1991 paper, Lifton shared the following definition that remains gospel among anti-cultists: “Cults can be identified by three characteristics: 1) a charismatic leader who increasingly becomes an object of worship…; 2)… coercive persuasion or thought reform; 3) economic, sexual, and other exploitation of group members by the leader and the ruling coterie.”

I’ve never been in one myself… although, I was deeply involved in the improv-comedy scene in the aughts, the doctrine of which specifically required saying, “Yes.” We also hugged each other indiscriminately, revered a bearded white dude, and passed out postcards that read “Don’t think.” My parents and sisters even had a conference call once regarding whether or not I was in a cult because I was at the theater every night, where I worked for free and spent money on a hierarchy of classes. Turns out, though, not a cult—because no one was manipulating my latent indoctrination in order to exploit

...more

Sean Keeler liked this

Columbus wasn’t even who we rethought he was. It was natural to assume he sought wealth out of basic avarice. But no. In truth, he needed all that gold because it’s expensive to bring back Jesus. Columbus even had an itemized, second coming to-do list. First, expel all Muslims from the Holy Land. That’s a big war—how would it be funded? Next, ensure the rebuilding of the temple in Jerusalem, an expensive architectural undertaking. Plus, convert everyone on earth to Christianity and rediscover the Garden of Eden, both of which would require multiple expeditions across the seas.

the New Testament book of Revelation—that freaky, ultraviolent hallucination that prophesies the end of the world—to

For example, he thought the world had a little tip at the top like a woman’s nipple, which is where paradise was. If he were alive today, I imagine that would be on his dating profile. Mostly, though, I tell you all of this to highlight that the Americas have been a staging ground for Christian apocalyptic fantasy since long before the Puritans arrived.

The radical Protestants believed, as apocalyptic thinkers always have, that the world contained good and evil forces—and nothing else. You were on one side or the other. Just as there was no middle ground, neither could the two compromise or reach a détente. Eradication was the only goal and each supernatural side had pursued it since the beginning of time.

In this monomyth, as they call it, tropes abound. The police chief is clumsy and overweight. The senator conspires with the villain. Cities are full of vice, while rural areas are populated by good and simple people. Women are either lustful temptresses or weak pacifists. The hero, meanwhile, is lonely and selfless, and despite how many women throw themselves at him, he never wants the girl (even when she is his wife). This last one is an ideology also echoed by Charles Manson when he said, “I don’t need broads. Every woman I ever had, she asked me to make love to her…. I can do without them.”

Then, out of nowhere, in Revelation, Jesus becomes a merciless punisher. The story—which in reality is a work of anti-Roman war propaganda written around 90 CE—is wildly, enthusiastically, euphorically violent. Here’s how it goes.

They believed God had promised it would be where Jesus returned to judge the quick and the dead and then reign forever with his chosen people, that is, Puritans in America. Then, this promise of America as privileged and perfect went secular, where it fueled a host of ideologies, including those supporting westward expansion.

The term failure of prophecy is best known from a 1950s research study of a UFO cult in Illinois known as the Seekers. Its leader, Dorothy Martin, said her extraterrestrial contacts told her most of the world would be destroyed in 1955:

After the event failed to occur, researchers witnessed group members struggling to hold two beliefs at once: their belief in the prophecy of a cataclysm, and their belief in their eyes and ears, which saw and heard no sign of saucer or flood. The researchers coined this psychological struggle cognitive dissonance.

And, of course, John of Patmos also experienced a failure of prophecy. Jesus had told his followers he would return within their lifetimes. It had been about sixty years. Jesus still hadn’t returned. Jews still suffered persecution. Instead of the Kingdom of God descending from heaven, the Romans ruled supreme. The prophecy had failed. Jesus’s followers needed a new one. So John delivered it. On

A 2022 poll conducted by the University of Maryland found that 61 percent of Republicans agreed: they supported declaring the United States a Christian nation.25

When parents complain that comics rot their kids’ brains, they’re actually kind of right.

In March 2021, on the heels of the January 6 insurrection, pollsters found that 15 percent of Americans agreed that “things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”

A cult agenda is like a fire sale at a mattress store: you must act now.

Enter World War I—the war to end all wars, an unmistakable reference to Armageddon, full stop, no matter how numb we have become to the phrase. (Note that in 2023, Donald Trump referenced the upcoming election by saying, “2024 is our final battle.”)

Amazingly, none of this is more far-fetched than theories from supposed scientists in that time period’s burgeoning field of eugenics—scientists who would help pass laws that sterilized between sixty and seventy thousand Americans.

A 2022 poll found the replacement theory was believed by half of Americans.

For example, studies suggest power diminishes empathy. The experience of feeling power causes a person to focus attention on themself. Since attention is a limited resource, that person necessarily focuses less on others.

This is a problem because it is the act of mirroring another’s expressions, positions, and gestures that creates the experience of empathy. (For example, if I hypothetically received Botox injections that resulted in me appearing slightly scared every time I tried to raise my eyebrows, I would, in turn, scare anyone I talked to.)

In a way, social media has allowed all of us to fashion ourselves as gods; seeking worship via likes, comments, subscriptions, and shares; approaching perfection via angles, filters, and photo editing.

As if superrich people would lose time organizing all of that! They’re too busy enjoying their yachts, jets, and, I don’t know, cloned pets.

We see it all over pop culture. Ever notice that comic book villains are brainiacs whose superior intelligence has corrupted them irrevocably and allowed them to devise innovative ways to destroy the world? Sure, plenty of superheroes are also superintelligent, but the character trait isn’t literally in their names, as it is for villains such as Egghead, the Brain, Brain Storm, Brainiac, Mister Mind, Mad Thinker, M.O.D.O.C. (Mental Organism Designed Only for Computing), and the Riddler. In reality, of course, villains are rarely known for intelligence, as evidenced by the character traits

...more

Quakers also protested by taking off their clothes. Called “the practice of going naked,” it was intended to shame Puritans who, Quakers said, hid beneath the metaphorical dressings of authority, status, or wealth. In short, every new sect believes its predecessors are going to hell while it’s getting it right, so it may as well pull out its tits.

And how is it possible for a group with power to continually maintain it has none? Identity. By the time Reagan was in office, Mattson argues that the postmodern conservative had “embraced the status of permanent rebel against a liberal establishment, even though that liberal establishment was rather rickety by that point.” Clinging to such a status provides one, no matter the movement, with certain privileges. For example, because rebels lack authority, they need not be held accountable; their persecuted status inherently legitimizes their needs and desires; and if they’re fighting a tyrant,

...more

This conundrum led Paul Mazur, a banker at Lehman Brothers, to write, “We must shift America from a needs, to a desires culture. People must be trained to desire, to want new things even before the old had been entirely consumed.”

But perhaps his most insidious campaign was to instill in Americans the belief that we should buy products not because we need them, but as a way to express our inner sense of self.

He called this the “engineering of consent.” The result of this irrational-desire sating was a happy and docile public. His daughter Anne Bernays says he viewed it as a kind of “enlightened despotism.”

can stare through your body as I die.” Moglen diagnosed Bojorquez with “acute psychotic reaction secondary to est training.”52 The seminar name was in the diagnosis, which frankly is a move I wish more physicians were brave enough to make: obesity as a secondary reaction to the Frito-Lay marketing department; hypertension as a secondary reaction to working for Jeff Bezos.

They could control their health through thoughts alone. Americans love agency, whether it’s a can-do attitude from a motivational seminar or believing we can affect when and where Jesus will return for Judgment Day. Agency is an American panacea.

Measurements of happiness in America peaked in the 1990s and have slowly declined since 2000. Between 1990 and 2018, the number of people who say they’re unhappy has risen by 50 percent.

But it’s also a market truth that a customer without needs is not a customer at all. Like automobiles and smartphones, self-help exhibits a certain amount of planned obsolescence. The industry makes more money when it appears to help but in reality doesn’t.

An egregious example is skin-care products that not only fail to achieve their bombastic claims, but also inhibit the skin’s natural ability to achieve those same goals. Your skin gets worse. You buy more products. What they actually sell is addiction.

When someone says no one else is telling you the truth, the liar is the one talking.

classic tool of the oppressor is to keep those beneath them in battle with one another. It was an ingenious development to next convince people to internalize such a battle. Now every person is fighting themself.

American culture teaches that success comes from endless striving, tireless work, and the motivated positive belief system that allows for those. That formula simply isn’t accurate. Most impoverished and marginalized citizens in our country will never achieve financial success.

In the mid-1800s, when machines came to replace the largely Black railroad labor, Henry, according to legend, challenged a machine to a contest, beat it, and then died on the spot. James argues the poor health outcomes of John Henryism result not only from societal stressors, but also specifically from the can-do hard-work attitude that leads us to believe we can overcome any obstacle.

It’s far more lucrative to convince have-nots that they can think their way out of problems by buying into certain mindset-driven belief systems. This is the twenty-first-century version of “let them eat cake”—the cake being the wealth and happiness promised by the American dream.

We need other people. Maybe the thing we feel is missing in our lives—the thing we keep trying to purchase from those preacherpreneurs, whether in pill bottles or conference rooms—is really just simple human connection. By encouraging us to turn ever inward, the personal-growth and self-help movements isolate us from one another. Consumerism also separates us, of course, escalating the assault into a one-two punch.

A 2018 study identified among its participants two basic strategies for seeking happiness: one social and one individual. The study determined that people with goals of “seeing friends and family more, joining a nonprofit, or helping people in need” reported increased life satisfaction a year later. Those who focused on goals such as “staying healthy, finding a better job, or quitting smoking” reported no increase in life satisfaction. In fact, “the self-focused road to happiness was even less effective than having no plans for action at all.”100 Research consistently finds that social

...more

This is the definition of a closed system, where an organization’s salespeople are also its end users, buying products at inflated prices, while profits move to the top of the chain. In other words, it’s a pyramid scheme, a wealth-redistribution system: those at the bottom pay in, but only receive money if they’re able to continue building the pyramid’s base beneath them, which becomes increasingly difficult as the pyramid grows. The more confusing the numbers and math, the harder it is to ascertain the grift.

Cultures affected by the Protestant Reformation became “obsessed with the idea of defining right and wrong in an objective way that everyone can agree with,” scholar Angus Fletcher told me. “Once you have that, that’s the end of stories because they all become allegories.”

The Lucky Twist is bludgeoned anew almost annually by Disney. The refusal to acknowledge luck as a force in the world is central to cultlike thinking.

In contrast, the fairy tales of Perrault and Disney can lead us to catastrophize by causing our brains to think, Fletcher writes, “Since my efforts have come to no good, then I must be no good…. I’ll keep failing forever,” and “Maybe I’m unhappy because I deserve to be unhappy.”

“These deeper emotional processes have been nuked by modern fairy tales,” Fletcher explains. “As a result, kids are coming out with more anxiety and anger. They think of everything in terms of right or wrong. If something’s wrong, it’s either their fault or somebody else’s.” Shame or blame. Victim or righteous. Damned or saved. Ursula or Ariel.

That same year, Whole Foods announced the end of medical benefits for all part-time workers, a move that annually saves the company the same amount that its overlord, Jeff Bezos, makes in two hours.