More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

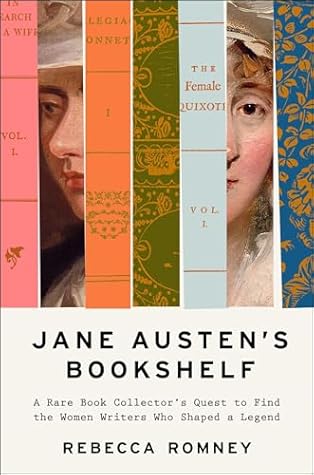

Jane Austen's Bookshelf: A Rare Book Collector's Quest to Find the Women Writers Who Shaped a Legend

Read between

August 12 - August 23, 2025

The star evidence: the phrase “pride and prejudice” came from Burney’s second novel, Cecilia (1782). Frances Burney, it turns out, had been one of Austen’s favorite authors.

Austen read William Shakespeare, John Milton, Daniel Defoe, and Samuel Richardson, all authors I had read. She also read Frances Burney, Ann Radcliffe, Charlotte Lennox, Hannah More, Charlotte Smith, Elizabeth Inchbald, Hester Piozzi, and Maria Edgeworth, all authors I hadn’t.

It was unsettling to realize I had read so many of the men on Austen’s bookshelf, but none of the women.

“And what are you reading, Miss—?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.

To call Austen “the first great woman writer in English,” really, is to call her the first British woman accepted in the Western canon.

I spent years wishing that Austen had authored more books. It didn’t even occur to me that there were women writers whom Austen had used as models—and whose books I could read, too.

Books give us a window into the minds of others, but they also help us know our own.

A reader says, “Which book do I want to read?” A collector says, “Which copy of this book do I want to find?” A reader falls in love with the story in the book. A collector falls in love with the story of the book.

This is the story of how I collected books by, and books about, eight women writers whose works Jane Austen read, but who no longer have the widespread readership they once enjoyed.

This is part of what makes Austen’s novels classics: they feel fresh to readers over two centuries after their publication.

The publication of Mansfield Park brought out another important fan, the prince regent. The regent was the eldest child of King George III, the acting monarch in his father’s stead since 1811, due to the king’s mental illness. (This is where the name for the time period we associate with Austen, “the Regency,” comes from; it covers 1811 to 1820, after which the regent became King George IV.)

These editions are in great demand by collectors, and I nab one for my rare book shop at every opportunity. From this point forward Austen’s novels remained in circulation with readers through numerous popular reprints—as documented by another book collector, the scholar Janine Barchas, who hunted down cheap, beat-up, and well-marked copies of these humble and fascinating productions in The Lost Books of Jane Austen (2019).

Among Burney’s four novels, Evelina was the most frequently published after her death. In the Victorian period, it was often praised as one of the greatest novels of the bygone Georgian era.

The principle of “the journey, not the destination” is what guides modern popular romance. But it’s also what guides modern popular mysteries.

Most mysteries begin with a crime and end with it solved. Most romances begin with a spark and end with a happy relationship. It’s the push and pull throughout the narrative that makes these genres enjoyable. Mysteries and romances both thrive on the gradual reveal.

Among those whose first romance was published by Odyssey are Donna Hill, Eboni Snoe, and Francis Ray, all of whom would publish books with Arabesque, the first big press line dedicated to Black romances, upon its rollout in 1994.

Tucked between couch, cat, and blankets, I settled in to read a book that Austen had loved.

In the period when Radcliffe, Burney, and Austen were publishing, more women published novels than men.

After reading Udolpho, I’ve developed a better appreciation for that central element of the gothic, the allure of landscape as character.

On the one hand, we come back to certain books because we want to experience, again, the feelings they first sparked. But books inevitably change with us. We notice new aspects of old favorites because our lives are different.

I had always enjoyed Austen’s wit, and now I was enjoying the wit of her predecessors. To my surprise, I found that The Female Quixote was far wittier than any of Austen’s novels. The “best” book is not necessarily the canonical one.

What we feel when we read does not remain on the page. We take it with us. We absorb it. It doesn’t have to change us, exactly (though it can), but it does affect us. It becomes part of the accumulation of all the little moments that make up our lives.

Similar to Smith, Charles Dickens was often paid by the installment, and thus he wrote epic novels spread across hundreds of pages.

It is natural that novels about women in this era would focus on the most critical point in a woman’s life, one of the few moments where she exercised power: the question of marriage. Those who denigrate courtship novels rarely consider these plots with the law of coverture in mind. When a man has that much control over your life and your children’s lives, the kind of man you marry can literally be a question of life or death. The history of English courtship novels is a literary history of women’s protest against the femme couverte.

Collectors, curators, dealers: we might have different roles, but we share the same goal. We preserve material histories. We keep the evidence. It’s a critical step that allows for the next one, where we look back at the past to make meaning from it.

Because novels of the late eighteenth century had a Heroine Problem. A heroine must experience something remarkable to hold the reader’s interest; yet in this era, saying that a woman had “adventures” was a euphemism for illicit liaisons that would likely lead to being cast out of high society. She must be both faultless and yet, somehow, not boring. That’s the Heroine Problem: How could authors compose an exciting story when moral authorities demanded that their main character never be a “bad example” to other young women readers?

Despite our cultural admiration for the “lone genius,” no thinker works in a vacuum.

Like so many women before me, I had felt alone as a solitary reader. As a collector investigating Austen’s favorite women writers, I found the warmth and affirmation of models. I didn’t “discover” these writers; I reconnected with them, like my predecessors had done before me.