More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

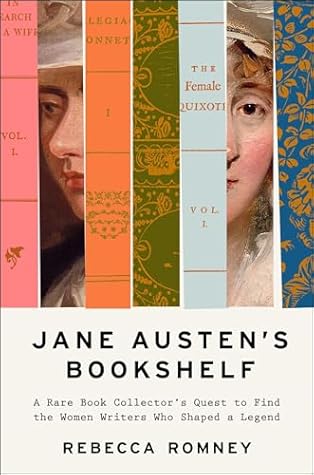

Jane Austen's Bookshelf: A Rare Book Collector's Quest to Find the Women Writers Who Shaped a Legend

Read between

April 24 - June 6, 2025

In his Sermons, Fordyce stated that the only kind of woman who would read any of the racier novels available at the time “must in her soul be a prostitute, let her reputation in life be what it will.” That is a real quote. From a book. Fordyce continued to proclaim that those who read such novels “carry on their very forehead the mark of the beast.” To Fordyce, novels might as well be a device for punishment found in a circle of Dante’s Hell: they are an “infernal brood” that commit “rank treason against [… ] Virtue”

CindySR liked this

The criticism of novel readers for wanting happy endings themselves had been argued for decades, as in a 1754 op-ed in The World that asserted “this doctrine of ideal happiness is calculated for the meridian of Bedlam.”

the feeling soon morphed into dread. Even while maintaining anonymity, she realized that publishing a book meant people might actually read it. It was an “exceeding odd sensation,” Burney admitted, “when I consider that it is now in the power of any and every body to read what I so carefully hoarded even from my best Friends.” She felt suddenly exposed.

According to Doody, “ ‘Fanny’ is a patronizing diminutive. It

As a result, this collection is now held at the renowned Lilly Library at Indiana University, accessible to scholars for research, to professors for teaching, to students for discovery—and, according to Lilly Library policy, to anyone who takes the time to put in a request to see the books, for any reason at all.

The seeds of Radcliffe’s fall were first sewn in 1797.

wanted to fight back against Wordsworth and Scott too. I was a Sherlockian at heart, an investigator, and I valued evidence. Critics used their words; I used my shelves.

Books are not static things. I’ve said that one reason I love reading is that I can examine the emotions it stirs safely from a distance, at my own pace. When I’m rereading, I’m doing that, and more. I’m remembering the emotions of the last read. I am remembering my past self. Simultaneously, I’m noticing the emotions of this read. I am marking the outlines of my current self. In that way, reading is not a separate act from the rest of my life. It is central to it.

For me, it’s also an antidote to the relentlessly disembodied experience of our digital lives. Collating a book gives me a moment to slow down, to become aware of my physical surroundings again, to appreciate their materiality. I am not only my avatar on the screen; I am a person, sitting at a desk, turning the pages of a book, one that another person wrote, and other people printed, and still other people read. I am real. They are real.

Lennox laid the blame for the disruption on another playwright, Richard Cumberland, who was known for such tactics. He feared that Lennox would encourage more women writers to stage plays, and that would mean fewer opportunities for him. He wasn’t wrong: there were a limited number of patents, or licenses, to stage plays in London in this period. He didn’t want more competition for the few spots available. This is the bigotry of the small-minded; in a scarcity environment, Cumberland wanted to win by ensuring he and his friends were the only players, not because they produced the best work.

Lennox’s experiences with such bad faith arguments—Cumberland attacking for fear of the competition, or Garrick and those theatergoers taking it personally when she looked at Shakespeare critically—have plenty of parallels today. A teacher advocates reading more works by contemporary people of color in classrooms, and some parent inevitably Cumberlands all over that: “If we read more books by contemporary people of color, when will we ever read the important dead white men?” they say, while somehow missing that the syllabus is still well populated with those very authors.

Yet when I started the first chapter of Coelebs, I could barely get through a paragraph without huffing in annoyance at some sanctimonious comment.

Reading is a solitary act that nevertheless connects you to others. It sets your interiority ablaze with ideas, connections, disagreements, or pleasures. In the process, you also learn to recognize—and to value—the world inside your own mind.

This copy was published in Boston in 1802. Three years earlier, in 1799, the first edition was issued in London at arguably the height of Hannah More’s influence as a public moralist. I hadn’t gone looking for a copy of this. But now it was here, I could no longer ignore it. The season was finally turning, and I prepared myself to read. I pulled out wool socks and a quilted blanket. I made chai, listening to Tori Amos as I ground the green cardamom pods and star anise, macerated the ginger, steeped the tea leaves. Curled up in my armchair, I opened the ragged book to the first leaves, the

...more

Across editions, across generations, I followed the evidence. I might not ever know the true answer to the source of Austen’s phrase, but the investigation itself thrilled me.

The Monthly Review similarly complimented it for that balance—“though probability is not violated, surprize is constantly awakened”—and highlighted its superiority of style: “A vein of elegant simplicity runs through the whole.”

But in Austen’s world, steadiness is strength.

Reading is not separate from life. It is a thread of life. In the

Piozzi was, according to Margaret D’Ezio, searching for a way to be an author true to herself in “a literary world still dominated by men.” By taking this hybrid approach, Piozzi brought her social, feminine touch to these traditionally staid, masculine spheres.

The mechanics of the profession had led my colleagues and me here. Johnson was more famous: more sellable. Therefore he is mentioned more prominently and more often. At the first rare book firm where I worked, we jokingly referred to the “Shakespeare Principle”: any rare book becomes more sellable if it can be tied in some way to Shakespeare. An

published thirteen years after the first edition. The concept of the first edition so dominates the rare book marketplace that most people don’t even realize book collecting doesn’t have to be about first editions at all. Once you realize this—that you don’t have to chase after what everyone else is seeking, that you can go your own way—all sorts of new paths open up.

Sara Ahmed captured my growing sentiment when she described citation as feminist work in Living a Feminist Life: “Citation is how we acknowledge our debt to those who came before; those who helped us find our way when the way was obscured because we deviated from the paths we were told to follow.” Like collecting, citation is a form of preservation. I cite these writers not only to acknowledge them, but also to form a connection with them.

Flickering ghosts, here again. I love the cover of the first edition of How to Suppress Women’s Writing because it prints each fallacy that Russ dissects in the book. “She didn’t write it.”

Nevertheless, we have decided that Austen is the best. And maybe she is, in some ways. But if we’re using comparison as a tool for rating authors, it’s not difficult to flip that narrative. Austen paints with a smaller palette than Burney. She is not as moving as Radcliffe. She is less daring than Lennox. She has less conviction than Hannah More. She is less philosophical than Smith. She is not as witty as Inchbald. She doesn’t have as much heart as Piozzi. She lacks the depth of wisdom of Edgeworth. But does that change my love for Austen? Of course not. When we use comparison as a way to

...more

Such an approach limits the potential of our reading, making the canon function as “yes, but”—as when we assume a book is no longer canonical because it isn’t any good. The canon is most useful when we say “yes, and”—using it as a starting point for

a richer and more expansive approach t...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

And #11: “Your classic author is the one you cannot remain indifferent to, who helps you to define yourself in relation to him, even in dispute with him” [emphasis original]. By that definition, these authors were my classics now.