More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

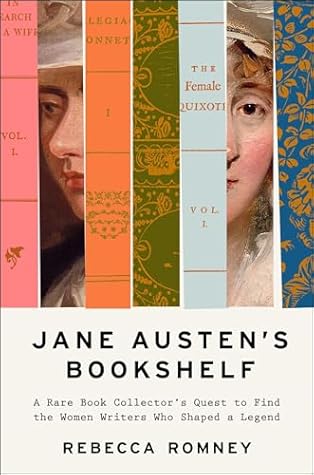

Jane Austen's Bookshelf: A Rare Book Collector's Quest to Find the Women Writers Who Shaped a Legend

Read between

November 20 - December 5, 2025

Instead of a flashy modern edition of Pride and Prejudice, this woman had a rather ugly one, bound in drab brown paper boards resembling dilapidated cardboard. It also bore an unusual revised title, Elizabeth Bennet; or, Pride and Prejudice. Despite its humble appearance, I knew the book was incredibly rare. It was the first edition of Pride and Prejudice published in the United States, from 1832.

I have always been drawn to Austen’s confidence, how she guides the reader through her heroines’ struggles and uncertainties.

Before a book is offered for sale, we rare book dealers record its physical attributes: Is it bound in cloth? Leather? Does it have any damage? Signs of previous ownership? We also often write a brief summary of its importance, drawing on the work of other experts in our field and surrounding fields—not just literary critics and biographers, but also book historians, or scholars who study the history of the book. We call the result a catalog description, which becomes our official documentation for that rare book.

Not all books are collected because they are first editions. Some are collected for their beauty.

But even when I do, I care about the story in the book—and the story of the book. I want to know what the book is about.

To be a rare book dealer is to appreciate that the book itself—the object—can be as interesting as its text.

I like to ask questions, approaching books like a detective. My job is to investigate each book’s story, its importance.

The star evidence: the phrase “pride and prejudice” came from Burney’s second novel, Cecilia (1782). Frances Burney, it turns out, had been one of Austen’s favorite authors. She wrote courtship novels very like Austen’s, focused on young heroines navigating the difficulties of finding love.

Burney was one of the most successful novelists of Austen’s lifetime.

I was picking up on clues, sprinkled about in the works of Austen like bread crumbs, that pointed toward the women writers she admired.

The period when Austen did most of her formative reading “was one of the most fertile, diverse, and adventurous periods of novel-writing in English history,” the author asserted—for one more paragraph, before moving straight to Austen and Walter Scott.

Austen read William Shakespeare, John Milton, Daniel Defoe, and Samuel Richardson, all authors I had read. She also read Frances Burney, Ann Radcliffe, Charlotte Lennox, Hannah More, Charlotte Smith, Elizabeth Inchbald, Hester Piozzi, and Maria Edgeworth, all authors I hadn’t. They were part of Austen’s bookshelf, but they had disappeared entirely from mine—and largely from that Leading Literary Theorist’s bookshelf as well. It was unsettling to realize I had read so many of the men on Austen’s bookshelf, but none of the women. Critical authorities like this one had provided the foundation for

...more

Burney had been writing a novel in secret. She felt terrible shame about it. Her father was out of the house, on a trip: now was her chance. She gathered up all the evidence, dumped it into an enormous pile in the garden, and burned it. Her little sister, the only one who knew her secret, watched the bonfire with tears streaming down her cheeks. The flames consumed all of Burney’s manuscripts.

She published her first novel anonymously, but she did not remain anonymous for long. Over the years, she published three further novels, all eagerly sought by her reading public—including an aspiring author in the village of Steventon, Hampshire, named Jane Austen. In Austen’s impassioned defense of novels in Northanger Abbey, she named as examples three novels “in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed.” Of those three, two were by Burney. But before them came Burney’s first published novel: the one she could not bring herself to destroy. It was called Evelina.

Evelina tells the story of an orphan who leaves her guardian’s home in the country at seventeen to visit London for the first time.

The basic framework of the book follows an established form: a coming-of-age tale in which the protagonist undergoes various trials associated with growing up (and typically ending in marriage). Other examples include Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740), which tells the story of a working-class girl who resists the advances of a rich suitor until he mends his ways and proposes to her; and Henry Fielding’s The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749), the story of another orphan who must find his way to happiness despite the obstacles created by his status as a bastard.

The first answer, the one that’s easy to reach for, is that Burney’s novels probably weren’t good. This is one of the main reasons why a canon exists, right? We cannot possibly read everything, and we often seek the opinions of other trusted readers to help us determine what to prioritize.

But there was evidence to the contrary: Austen’s praise. If I loved Austen’s books, and Austen loved Burney’s, certainly these books were worth looking into. At the very least, my esteem for Austen suggested they deserved an honest chance.

Most people assume that they should not be writing in their books—but book historians love it. One of the most difficult questions book historians seek to answer is: How did everyday readers respond to books? We often have access to printed professional reviews, but what everyday readers thought of a book is rarely recorded for posterity.

Frances Burney was born in 1752 in a port town about one hundred miles north of London. She was the third oldest among six children, and ultimately among eight when her father remarried a few years after her mother’s death in 1762. When Burney was eight years old, the Burneys moved to London. There, the family flourished. Frances, remembered as the most celebrated member of her family today, was once considered the dunce of the lot.

Her father Charles was a charismatic music master and published historian who counted among his closest friends David Garrick, the biggest theater star of the era;

Her older brother James twice voyaged with Captain Cook, and later became the informal interpreter of Omai, a man from the Society Islands who traveled back with Cook on his first voyage and became the toast of London. Her older sister Esther was a musical child prodigy, lauded by royalty, the sensation of the scene before the next young savants appeared—Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Maria Anna Mozart, his sister.

Charles Burney only published nonfiction, and he owned only one novel in his entire library (Henry Fielding’s Amelia).

In reading about Burney’s childhood, I was struck by her belief that novel writing was a bad habit. Her sense of shame baffled me, especially in the context of her gifted family.

One of the best ways to get a sense of the everyday currents of a given society is to swim about in its newspapers, literary magazines, and essays.

Conduct books, a popular genre of the era meant to educate young people (and especially young women) in propriety, etiquette, and taste, were particularly critical of them.

“They excite a spirit of relaxation,” explained Hannah More without a speck of irony. She was certain they made young women lazy, which in turn led to loose morals. Should that jump in logic seem unbelievable to modern readers, I offer receipts: More says that novels meant for amusement “nourish a vain and visionary indolence, which lays the mind open to error and the heart to seduction.” One popular conduct book by Thomas Gisborne—a work we know Austen read—coyly says, “To indulge in a practice of reading [novels] is, in several other particulars, liable to produce mischievous effects.”

Of course, everyone read novels, not just women, and not just younger women. But they were most often criticized as dangerous for that particular demographic, who were considered so impressionable that they were susceptible to imitating what they read.

In 1761, the year Frances Burney turned nine, a gentlewoman named Sarah Pennington published a popular conduct book in the form of a letter to her daughters, in which she advised that novels “are apt to give a romantic Turn to the Mind, that is often productive of great Errors in Judgment, and fatal Mistakes in Conduct; of this I have seen frequent Instances, and therefore advise you never to meddle with this Tribe of Scribblers.”

“Believe me,” he said, “I know several unmarried ladies, who in all probability had been long ago good wives and mothers, if their imaginations had not been early perverted with the chimerical ideas of romantic love.” Yes, what an awful shame that would be: women refusing to settle because novels depicted men of higher standards.

They often encouraged women to choose a marriage partner based upon mutual esteem and proof of his good conduct, rather than prioritizing a match of families and finance that more typically made upper-class marriages in this era.

According to the modern scholar Judith Phillips Stanton, the number of women publishing increased “around 50 percent every decade starting in the 1760s.”

In fact, women wrote more than 50 percent of novels published.

Udolpho usually appears in one sentence of literary surveys, in which they briefly pause to name-check a couple of gothics, the genre that Udolpho made popular (more on that later). But I confess, none of those drive-by mentions had ever moved me to consider investigating the book myself. The word I associated with it: melodramatic. In the eighteenth century, readers and critics alike considered Udolpho a masterpiece.

Ann Radcliffe was born in London in 1764, making her about twelve years younger than Burney and eleven years older than Austen.

Whether by eighteenth-century standards or twenty-first-century ones, young Ann’s education was unconventional. While she was barred from an extensive classical program more commonly granted to boys of the genteel class into which she was born, she did receive training that few of her generation could match. As a child, Ann became the ward of her uncle Thomas Bentley during a period when her father transitioned careers. Bentley was famous for partnering with Josiah Wedgwood, whose innovations in ceramics made him a leading producer of fine china and other dishware.