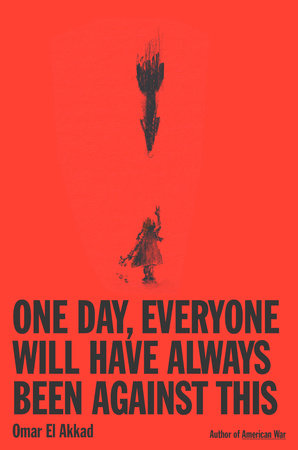

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 12 - October 16, 2025

“expat” is largely reserved for white Westerners who leave their homes for another country, usually because the money’s better there. When other people do this, they might be deemed “aliens” or “illegals” or at best “economic migrants.”

Whitney Luken liked this

It is a hallmark of failing societies, I’ve learned, this requirement that one always be in possession of a valid reason to exist.

Whitney Luken liked this

Rules, conventions, morals, reality itself: all exist so long as their existence is convenient to the preservation of power. Otherwise, they, like all else, are expendable.

Whitney Luken liked this

Under foreign and then local rule, the central directive never changed: Know your place. It’s a frequent, nauseating political inheritance: come to experience the world under the reign of someone who thinks of you as subhuman, as undeserving of a future, and an ugly impression is settled that true power is the ability to do the same to someone else. The foreigners had departed; there was no one left to do it to but our own.

We are all governed by chance. We are all subjects of distance.

Whose nonexistence is necessary to the self-conception of this place, and how uncontrollable is the rage whenever that nonexistence is violated?

the repression, the sheer docility expected of everyone on all matters political or social, the gaggle of idiot Dear Leaders whose embellished jawlines were plastered on most every vertical public surface.

knew for certain that there were deep ugly cracks in the bedrock of this thing called “the free world.” And yet I believed the cracks could be fixed, that the thing at the core, whatever it was, was salvageable.

(The very history of the word “genocide,” meant as a mechanic of forewarning rather than some after-the-fact resolution, is littered with instances of the world’s most powerful governments going to whatever lengths they can to avoid its usage, because usage is attached to obligation. It was never intended to be enough to simply call something genocide: one is required to act.)

Whitney Luken liked this

For members of every generation, there comes a moment of complete and completely emptying disgust when it is revealed there is only a hollow. A completely malleable thing whose primary use is not the opposition of evil or administration of justice but the preservation of existing power.

Whitney Luken liked this

Just for a moment, for the greater good, cease to believe that this particular group of people, from whose experience we are already so safely distanced, are human.

Immigration is barely a phenomenon of physical or cultural geography; the landscape marks the smallest change.

In the Middle East I’d seen North Americans and Europeans arrive and immediately cocoon themselves into gated compounds and gated friendships.

Whitney Luken liked this

So normalized was this walling off that a Westerner could spend decades in a place like Qatar and only briefly contend with the inconvenience...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

something else changes most radically in the psychology of someone who leaves home: a relative distance between the person one is and the person they must become. Westerners in Qatar left the smallness of past selves behind. They were handed large offices and important-sounding job titles and Filipina housemaids and a sense of grandeur that I suspect many of them always knew, deep down, was little more than the formal dressing of life in a petrostate. And just as they (and we, and most everyone who comes to places like Qatar to do anything other than manual labor) became bigger, in Montreal my

...more

I believed, firmly, not in any ceiling on what this society would allow to be done to people like me, but in what it would allow done to itself, its own rights and freedoms and principles.

We were told to always bribe as close to the going rate as possible, never more, so as to not contribute to inflation.

left to their own devices, most human beings are useless at estimating time, distance, or space.

They say what you’re supposed to do, in this line of work, is comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.

A reporter is supposed to agitate against silence.

And on the heels of that realization, a converse one: I begin to suspect that the principles holding up this place might not withstand as much as I first thought. That the entire edifice of equality under law and process, of fair treatment, could just as easily be set aside to reward those who belong as to punish those who don’t. A hard ceiling for some, no floor for others.

American liberalism demands a rhetorical politeness from which the fascistic iteration of the modern Republican Party is fully free.

Whitney Luken liked this

for an even remotely functioning conscience, there exists a point beyond which relative harm can no longer offset absolute evil.

You are free to say so long as what you say is acceptable.

The moral component of history, the most necessary component, is simply a single question, asked over and over again: When it mattered, who sided with justice and who sided with power? What makes moments such as this one so dangerous, so clarifying, is that one way or another everyone is forced to answer.

It’s no use, in the end, to scream again and again at the cold, cocooned center of power: I need you, just this once, to be the thing you pretend to be.

If the people well served by a system that condones such butchery ever truly believed the same butchery could one day be inflicted on them, they’d tear the system down tomorrow.

There’s a convenience to having modular opinions; it’s why so many liberal American politicians slip an occasional reference of concern about Palestinian civilians into their statements of unconditional support for Israel. Should the violence become politically burdensome, they can simply expand that part of the statement as necessary, like one of those dinner tables you lengthen to accommodate more guests than you expected.

In almost every craft talk I’ve ever given, I find myself returning to Hemingway’s Iceberg principle—the notion that the vast majority of what is known about a story should exist beneath the surface of that story, unseen. It’s one of the most well-worn pieces of writing advice, a close cousin of the directive “Show, don’t tell.”

hang on to the hope that, presented with proof of injustice, the majority human reflex is to act against it.

In a perfect world, politics is boring, informed by debate but assured of a mutual understanding that the civic good matters. It’s tree-cutting permits and public transport levies and people who go to school for years and years to learn how to best pass a thoroughfare through a residential area. Republicanism, in its current form, proposes the exact opposite—treason trials for political opponents, the stripping away of any societal covenant, a war on expertise. In the right-wing vision of America, every societal interaction is an organ harvest, something vital snatched from the civic body,

...more

Whitney Luken liked this

It’s difficult to live in this country in this moment and not come to the conclusion that the principal concern of the modern American liberal is, at all times, not what one does or believes or supports or opposes, but what one is seen to be. From this outcome, everything is reverse-engineered. Being seen as someone who believes in justice—not the messy, fraught work of achieving it—is the starting point of any conversation on justice. Saying the right slogans supersedes whatever it is those slogans are supposed to oblige. It makes sense—when there are no real personal stakes, when the

...more

Whitney Luken liked this

if the Hillary Clintons of the world can muster great outrage at the fortunes of the Barbie movie at the Oscars but nothing at population-wide military murder sprees, then every Republican will always be able to say, truthfully: At least there’s no contradiction between what I am, what I claim concerns me, and what I plan to do.

While any liberal politician who succumbs to the lure of this framing may benefit in the short term, there is an inevitable and deeply unpleasant terminus waiting. Eventually, the calculus becomes, on pragmatic terms, clear. How much worse can some hypothetical oppression be compared to the current, very real one, which has the additional indignity of being propped up politically and financially by the same Free World whose leaders simultaneously give impassioned speeches about their support for democracy? If both outcomes entail injury, why should anyone opt for the one that adds insult too?

One day the killing will be over, either because the oppressed will have their liberation or because there will be so few left to kill. We will be expected to forget any of it ever happened, to acknowledge it if need be but only in harmless, perfunctory ways. Many of us will, if only as a kind of psychological self-defense. So much lives and dies by the grace of endless forgetting. But so many will remember. We say that, sometimes, when it’s our children killed: Remember.

lasting consequences of the War on Terror years is an utter obliteration of the obvious moral case for nonviolence. The argument that violence in any form debases us and marks the instant failure of all involved is much more difficult to make when the state regularly engages in or approves of wholesale violence against civilians and combatants alike.

Colonialism demands history begin past the point of colonization precisely because, under those narrative conditions, the colonist’s every action is necessarily one of self-defense.

Power absent ethics rests on an unshakable ability and desire to punish active resistance—to beat and arrest and try to ruin the lives of people who block freeways and set up encampments and confront lawmakers. But such power has no idea what to do against negative resistance, against someone who refuses to buy or attend or align, who simply says: I will not be part of this. Against the one who walks away.

The first is outward: every derailment of normalcy matters when what’s becoming normal is a genocide. It doesn’t take much: by the standards of Western normalcy, where the possibility of a missile landing on one’s house or a military sniper murdering one’s children is so implausible as to be indistinguishable from science fiction, even minimal inconvenience is tantamount to apocalypse. The second is inward: every small act of resistance trains the muscle used to do it, in much the same way that turning one’s eyes from the horror strengthens that particular muscle, readies it to ignore even

...more

The system, predicated on endless feeding, is unable to imagine anything outside itself, let alone forms of resistance to itself.

The idea that walking away is childish and unproductive is predicated on the inability to imagine anything but a walking away from, never a walking away toward—never that there might exist another destination. The walking away is not nihilism, it’s not cynicism, it’s not doing nothing—it’s a form of engagement more honest, more soul-affirming, than anything the system was ever prepared to offer.

I don’t know how to make a person care for someone other than their own. Some days I can’t even do it myself.

Whitney Luken liked this