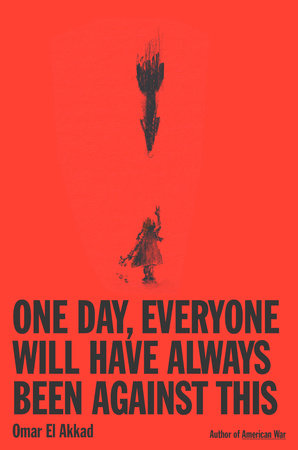

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 3 - September 11, 2025

It is a hallmark of failing societies, I’ve learned, this requirement that one always be in possession of a valid reason to exist.

Rules, conventions, morals, reality itself: all exist so long as their existence is convenient to the preservation of power. Otherwise, they, like all else, are expendable.

One of the hallmarks of Western liberalism is an assumption, in hindsight, of virtuous resistance as the only polite expectation of people on the receiving end of colonialism. While the terrible thing is happening—while the land is still being stolen and the natives still being killed—any form of opposition is terroristic and must be crushed for the sake of civilization. But decades, centuries later, when enough of the land has been stolen and enough of the natives killed, it is safe enough to venerate resistance in hindsight.

We are all governed by chance. We are all subjects of distance.

Whose nonexistence is necessary to the self-conception of this place, and how uncontrollable is the rage whenever that nonexistence is violated?

It was a bloodbath, orchestrated by exactly the kind of entity that thrives in the absence of anything resembling a future.

Once far enough removed, everyone will be properly aghast that any of this was allowed to happen. But for now, it’s just so much safer to look away, to keep one’s head down, periodically checking on the balance of polite society to see if it is not too troublesome yet to state what to the conscience was never unclear.

This is an account of a fracture, a breaking away from the notion that the polite, Western liberal ever stood for anything at all.

Just for a moment, for the greater good, cease to believe that this particular group of people, from whose experience we are already so safely distanced, are human.

What has happened, for all the future bloodshed it will prompt, will be remembered as the moment millions of people looked at the West, the rules-based order, the shell of modern liberalism and the capitalistic thing it serves, and said: I want nothing to do with this. Here, then, is an account of an ending.

The most glaring example in the Western world is Fox News, an entity that more than any other has normalized the practice of severing any relationship between the truth and what one wishes the truth to be.

Narrative power, maybe all power, was never about flaunting the rules, yelling at a cop, making trouble—it was about knowing that, for a privileged class, there existed a hard ceiling on the consequences.

That the entire edifice of equality under law and process, of fair treatment, could just as easily be set aside to reward those who belong as to punish those who don’t. A hard ceiling for some, no floor for others.

When those dying are deemed human enough to warrant discussion, discussion must be had. When they’re deemed nonhuman, discussion becomes offensive, an affront to civility.

The moral component of history, the most necessary component, is simply a single question, asked over and over again: When it mattered, who sided with justice and who sided with power? What makes moments such as this one so dangerous, so clarifying, is that one way or another everyone is forced to answer.

(As a matter of tactics, it is instructive to know that Western power must cater to a sizable swath of people who can be made to care or not care about any issue, any measure of human suffering, so long as it affects the constant availability and prompt delivery of their consumables and conveniences. As a matter of moral health, the same knowledge is horrifying.)

What good are words, severed from anything real?

They will instead support no one, vote for no one, wash their hands of any ordering of the world that results in choices no better than this. And the obvious centrist refrain—But do you want the deranged right wing to win?—should, after even a moment of self-reflection, yield to a far more important question: How empty does your message have to be for a deranged right wing to even have a chance of winning?

Fear obscures the necessity of its causing. No one has ever been unjustifiably afraid, not in their own mind.

A political system that won’t restrict firearms even after a shooter massacres classrooms full of children, a system that shrugs when a regime murders and dismembers a journalist because that regime controls an inordinate amount of oil, a system that won’t flinch at the images of starving babies when it has the power to save their lives—what manner of resistance can’t such a system learn to abide? What use is any of it, what use? But there is a use, always.

When the White House instructs its ambassador at the United Nations to veto a resolution, when a whole host of Western nations cut aid to the one agency trying most desperately to keep Palestinians from starving to death, when the president grieves over photos of dead babies he never saw but thinks nothing of thousands of very real dead children who in his mind are beneath mourning, there are no illusions on the part of anyone involved as to what these acts of severance are designed to achieve.

I know now there are people, some of them once very dear to me, to whom I will never speak again so long as I can help it. It’s the people who said nothing, who knew full well what was happening and said nothing because there was a personal risk to it, a chance of getting yelled at or, God forbid, a chance of professional ramifications. It’s the people who dug deeply into the paramount importance of their own safety, their own convenience. I feel no anger toward these people, not even frustration or disappointment, simply a kind of psychological leavetaking, an unspoken goodbye.

what Susan Sontag is supposed to have said about the great lesson of the Second World War: that 10 percent of people are fundamentally good, 10 are fundamentally evil, and the other 80 swayable in either direction.

I think instead of Virginia Woolf’s conversation with that lawyer over the images of the war’s dead: I cannot argue with you, cannot convince you of anything, because when you and I look at these pictures we see, fundamentally, different things.