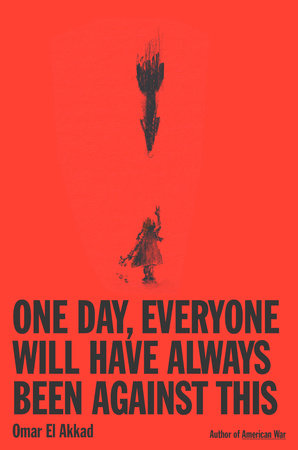

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 29 - June 30, 2025

It is instead the middle, the liberal, well-meaning, easily upset middle, that desperately needs the protection this kind of language provides. Because it is the middle of the empire that must look upon this and say: Yes, this is tragic, but necessary, because the alternative is barbarism. The alternative to the countless killed and maimed and orphaned and left without home without school without hospital and the screaming from under the rubble and the corpses disposed of by vultures and dogs and the days-old babies left to scream and starve, is barbarism.

It is a hallmark of failing societies, I’ve learned, this requirement that one always be in possession of a valid reason to exist.

When next this happens (and it will happen, again and again, because a people remain under occupation and because the relative compelling powers of both revenge and consequence warp beyond recognition once one has been made to bury their child), this same framing can always be used. The barbarians instigate and the civilized are forced to respond. The starting point of history can always be shifted, such that one side is always instigating, the other always justified in response.

Words exist only in hindsight; time passes over and around them like water along a canyon floor. In the year or so between when I write these words and when they are published, perhaps so many innocent people will have been killed, so many mass graves discovered, that it will not be so controversial to state plainly what is plainly known. But for now we argue, in this part of the world, the part not reduced to rubble, about how words make us feel. It’s a kind of pastime.

Once far enough removed, everyone will be properly aghast that any of this was allowed to happen. But for now, it’s just so much safer to look away, to keep one’s head down, periodically checking on the balance of polite society to see if it is not too troublesome yet to state what to the conscience was never unclear.

What has happened, for all the future bloodshed it will prompt, will be remembered as the moment millions of people looked at the West, the rules-based order, the shell of modern liberalism and the capitalistic thing it serves, and said: I want nothing to do with this. Here, then, is an account of an ending.

Americans and Europeans arrive and immediately cocoon themselves into gated compounds and gated friendships. So normalized was this walling off that a Westerner could spend decades in a place like Qatar and only briefly contend with the inconvenience of their host nation’s ways of living. (It would come as a genuine surprise to me, years later, when I came to the West and found that this precise thing was a routine accusation lobbed at people from my part of the world. We simply did not do enough to learn the language, the culture. We stubbornly refused to assimilate.)

There’s always been a contradiction at the heart of this enterprise. In the modern, well-dressed definition, adhered to in one form or another at almost every major newspaper, the journalist cannot be an activist, must remain allegiant to a self-erasing neutrality. Yet journalism at its core is one of the most activist endeavors there is. A reporter is supposed to agitate against power, against privilege. Against the slimy wall of press releases and PR nothingspeak that has come to protect every major business and government boardroom ever since Watergate. A reporter is supposed to agitate

...more

There’s a model of self-perception among some journalists that views the world as a playing field and the reporter as some combination of referee, scorekeeper, and play-by-play announcer. It’s a model that seeks to assign agency while maintaining the veneer of both neutrality and objectivity. If there’s a foul, the referee will call it, regardless of which team is responsible. The announcer will tell you what happened. The scorekeeper will tell you the results. No favor, no bias. One can see the consequences of this kind of model most frequently in political coverage, where the chief concern

...more

“Vote for the liberal though he harms you because the conservative will harm you more” starts to sound a lot like “Vote for the liberal though he harms you because the conservative might harm me, too.”

The moral component of history, the most necessary component, is simply a single question, asked over and over again: When it mattered, who sided with justice and who sided with power? What makes moments such as this one so dangerous, so clarifying, is that one way or another everyone is forced to answer.

It’s impossible to do the work of journalism, or at least serious journalism, and not be forced to make some kind of peace with the reality that you will be, many times over, a tourist in someone else’s misery. You will drop into the lives of people suffering the worst things human beings can do to one another. And no matter how empathetic or sincere or even apologetic for your privilege you may be, when you are done you will exercise the privilege of leaving.

A central privilege of being of this place becomes, then, the ability to hold two contradictory thoughts simultaneously. The first being the belief that one’s nation behaves in keeping with the scrappy righteousness of the underdog. The second being an unspoken understanding that, in reality, the most powerful nation in human history is no underdog, cannot possibly be one, but at least the immense violence implicit in the contradiction will always be inflicted on someone else.

There is an impulse in moments like this to appeal to self-interest. To say: These horrors you are allowing to happen, they will come to your doorstep one day; to repeat the famous phrase about who they came for first and who they’ll come for next. But this appeal cannot, in matter of fact, work. If the people well served by a system that condones such butchery ever truly believed the same butchery could one day be inflicted on them, they’d tear the system down tomorrow. And anyway, by the time such a thing happens, the rest of us will already be dead.

It is a source of great confusion first, then growing rage, among establishment Democrats that there might exist a sizable group of people in this country who quite simply cannot condone a real, ongoing genocide, no matter how much worse an alternative ruling party may be or do. This stance boggles a particular kind of liberal mind because such a conception of political affairs, applied with any regularity, forces the establishment to stand for something. It suddenly becomes insufficient to say: Elect us or else they will abolish abortion rights; elect us or they will put more migrants in

...more

But when voters decide they cannot in good conscience participate in the reelection of anyone who allows this starvation to happen, they are branded rubes at best, if not potential enablers of a fascist takeover of Western democracy. Because the individual cannot be allowed to walk away, cannot be afforded an all-encompassing right not to participate. Not when the entire system depends, in a very existential sense, on continued participation, on ever-increasing participation.

But then to see a group of U.S. veterans at a memorial for Aaron Bushnell, at the site of his protest; to see hundreds of thousands marching, taking ground outside the constituency offices of their elected officials; to watch even the normally anonymous executives of weapons manufacturers face both active and negative resistance, students protesting at the factories and dockworkers refusing to load the missiles onto the ships—to see these things is to know the sand is sticking to the teeth. The gears will grind to a halt one day, and the silence that waits then, for those who commended this

...more