More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

He’s twenty-three, too close to childhood and too far from it to find children of consequence.

He’s searching for the chain of requests, expectations, and subtle demands with which he believes women make prisoners of men.

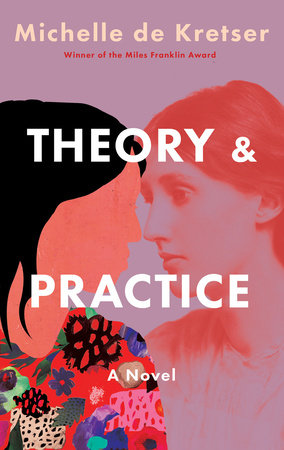

The smooth little word ‘and’ makes the transition from theory to practice seem effortless, but I’d rarely found that to be the case.

As I recalled thrashing about in the messy gap between the two, I began to see that my novel had stalled because it wasn’t the book I needed to write. The book I needed to write concerned breakdowns between theory and practice, and the material was overwhelming. Particles of it had entered my novel and jammed up its works.

Instead of shapeliness and disguise, I wanted a form that allowed for formlessness and mess. It occurred to me that one way to find that form might be to tell the truth.

The relationship between my theory exercises and the music I played must have been so obvious to my teacher that she neglected to point it out. It wasn’t in the least obvious to me. Theory and practice remained distinct activities that occupied separate rooms in my mind. In one I wrote in pencil on paper printed with staves, in the other I struck black and white notes on a keyboard, and no corridor linked the two.

We inhabited a world designed for the protection and pleasure of adults. We had no words for abuse and only the haziest notion of sex. What we knew for certain was that everything related to ‘down there’ was shameful. What we knew for certain was that to attract sexual attention was to be shamed.

The way to counter shame was to seek out solidarity. She was only twelve but she understood that.

I spent evenings lying on my bed, re-reading Woolf’s novels, all the while feeling guilty that I wasn’t reading Theory. Everything important that happened in that flat happened in my bed.

Theory had identified an authentically female way of writing, I told Anti. The Maternal sentence was liquid and nonlinear, swooping and looping, multidirectional, whorled. It disrupted norms. French feminists revered Woolf as a prime example of a writer in whose work the disruptive Maternal could be observed.

I’d raged silently, inwardly, censored by an internal critic who found jealousy a trite, despicable emotion, a morbid symptom that ran counter to feminist practice.

‘Artists used to think about art through art. Now they think about it through Theory. What happened to praxis?

I’ve never forgotten her unweaving of The Rainbow. It genuflected at Theory, but that was only a ritual to sanctify the essay’s serious, chewy business, namely the mauling of D. H. Lawrence.

Since the death of my father, responsibility for my mother had devolved upon me. Now she was my child as well as my mother.

I got to October 1917. The air felt different after that.

I asked Anti if she’d read A Room of One’s Own, and she asked if the pope shat in the woods. ‘That book explained my life.’ ‘That’s what I thought when I read it.’ ‘It explains the life of every woman on the planet.’

I thought about her/my/our Woolfmother. She was our Bildungstheorie, showing us how to understand ourselves in relation to the world. Our mothers closed doors in order to keep us safe and never stopped warning us about the dangers outside. The Woolfmother said, ‘Imagine!’ and opened doors in our minds. She was the one we turned to when our own mothers failed.

The Woolfmother outed herself as a snob and a racist and an anti-Semite, failing us because mothers are obliged to fail. But her writing about women inspired us and gave us courage because our imaginations were bigger than hers. Our imaginations projected us into sentences intended for upper-middle-class Englishwomen. They propelled us into a future in which we were artists and scholars and our lives were experimental adventures. In that future we could destroy the Woolfmother, rip her to pieces, and end up motherless and weeping. Or we could frame her, put her up on a wall, and keep her under

...more

Did Woolf’s diary represent one self, while her fiction and essays represented another? If her diary expressed private thoughts and her books expressed public ones, did that mean that her diary self was the true one? Was there a hierarchy of Woolfish selves, and, if so, was one more profound/more authentic/higher/better than the other? Also: Why were we reading her private diary?

Another metaphor for a diary is a collection of morbid symptoms.

Some years later, when I saw a trailer for The Lover, the film based on Marguerite Duras’s novel,

‘That’s the purpose of art,’ she said grandly. ‘It gives form to experience. It makes sense of our lives.’

The Reason Under All The Reasons for not tearing down the Woolfmother: our mutual shiver of shame.

Anti mulled over this for a while. Then, ‘You know what, though? Didn’t Rushdie say that thing about the empire writing back? You could find inspiration there.’ She had Aristotle’s categorisation of human activities in mind, she said. ‘He distinguishes theoria, which increases knowledge, from praxis, which is action-for-itself. In between those two comes poiesis, which is action-for-making. Poiesis is creative. Make a film, paint, write a poem. Write back to Woolf.’

I understood why I was the only person I’d met at university with my name. I understood why I’d never read a novel written by a woman with my name. And I understood why I’d never come across a character with my name in a novel: being Common and Dumb, a woman with my name couldn’t possibly have an interior life.

‘Who will write the history of tears?’

Sometimes I fell asleep thinking about her and woke thinking about her the next day. Sometimes I remembered with incredulity that, just a few months before, I’d hardly thought of her at all. It encouraged me to believe that I could easily return to that state – it would require no more effort than opening a window or changing my shoes. But every day, under every aspect of my life, Olivia ran like a stream. In this world only one of us two could be happy, I thought. Why shouldn’t the bluebird of happiness fly my way?

At the end of Tolstoy’s novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich, someone watching over the dying man sees that the end is imminent and says, ‘It is finished.’ Ivan Ilyich, misunderstanding this, believes that death is finished. ‘It is no more,’ he thinks. He takes a breath and dies. At the start of winter I’d told Kit that we were finished. Later, I’d let myself believe that we were not. I’d been as contented as Ivan Ilyich, and as wrong.

Of course Leonard minded when his wife called him ‘the Jew’ or ‘my Jew’. Of course he didn’t show that he did. That was the meaning of assimilation: it trained us not to show that we minded. It trained us to pass. It trained us to disappear.

‘Ten minutes with her and I’d be calling for a gun,’ said Anti dreamily, contemplating her banner. ‘But she helped build my brain. You know?’

A Lover’s Discourse. It was expensive, but I bought it at once. Yes, yes, yes, I muttered orgasmically to myself as I read, yes, that’s it exactly. Barthes’ lover knew what it was like to be me. He desired and was foolish and waited and despaired. He was jealous. He recognised the complexity of jealousy. He obliged himself to accept non-exclusive relationships and wondered whether doing so was really an inverted conformism: ‘because I was ashamed to be jealous’.

I told my audience that Woolf had set out to find a fresh form in The Years, but had later abandoned the attempt. A fresh form represents a desire to see the world differently, but Woolf hadn’t managed to do so. The Years remained enclosed in the powerful fiction that the self-fulfilment of British women transcended the imperialism that enabled it. That was The Story Under The Story in The Years. Like the Indian at the party, it was a narrative presence denied a voice.

A daughter was obliged to point out her mother’s shortcomings; it couldn’t be helped. Had she expected applause for granting an Indian entry into an English drawing room on condition that he didn’t speak? The Woolfmother continued to avoid my eye, her creative-destructive energies fizzing, my boot print half obscuring her face.

Many years had to pass before I’d realise that life isn’t about wishes coming true but about the slow revelation of what we really wished.

thinking about a paradox described in A Lover’s Discourse: in triangular relationships, the rival, too, is loved, swelling in the lover’s obsessive mind while the loved one recedes.

Our letters and calls to each other dwindled as our lives swerved and swerved again. Time kept up its Now-Now-Now, and we didn’t pay attention to what was going on. We underestimated the pull of the horizon, we didn’t spot each other swirling out to sea.

What politics asked of us was to care about people we couldn’t see into, and the difficulty of that was the difficulty of life.

Three years into this century, my mother died. It’s what mothers do. Daughters tell themselves they’ve escaped, but that power reverts to mothers at the end.

A poet from Ghana remarked that the whole set-up, including the conference, perfectly illustrated an observation in V. S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River: ‘The Europeans wanted gold and slaves, like everybody else; but at the same time they wanted statues put up to themselves as people who had done good things for the slaves.’

he’d come to confuse realism with reality. It was her opinion that he was looking to life for the satisfactions provided by novels: the possibility of redemption, answers and patterns, motive and cause. Women were mocked for Bovarysme, but in her experience it was men who were swayed by well-worn narrative tropes. Life was random and cruel, she said, and she’d lost patience with his unwillingness to face that fact.