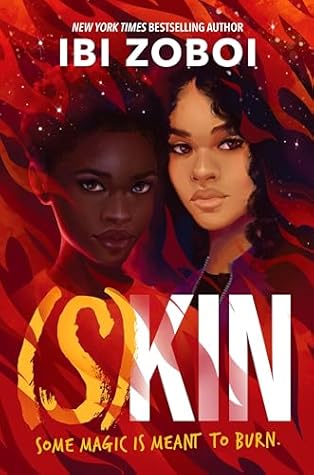

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

My face is wet with an ocean of tears. The salt stings my skin. And my guilt fills this entire house like thick smoke.

So he has not come in to pay his workers. And the workers will not be baking until he does. It is all my fault.

Even at the resorts on the islands, we came home. We could not be greedy with the work. There was always someone else who needed the hours, the tips, the pay, the job— and because of that, we had time and space to breath in life— Here, work is the life, and life is the work.

Good education here is as free as the wind.”

Jean-Pierre is not around to make us pay for the damage. Jean-Pierre is not around to also fix the damage.

Kate doesn’t like cooking. Dad thinks he’s a home chef. But still, we live off deliveries and takeouts from local restaurants, even though there’s a long list of foods I can’t eat.

“No, no, no,” Lourdes says. “It’s good food. Good for the, uh . . .” She rubs the back of her hand, and she already knows that something’s wrong with my skin. Hers is smooth, too smooth.

And it’s almost as if they already know each other. But I push that feeling down because I haven’t slept and the lines between my nightmares and reality are blurred now—

because on the islands, a black cat is not just an omen, it can be a hiding place for a soul.

His jawline is chiseled stone. His face is a sculpture.

All kinds of spirits were always coming after Jean-Pierre.”

“So you will work here forever? What kind of American dream is that?” “I didn’t come here to dream. I came here to live.

“I did not come here to live. I came here to dream,”

the red-tongued jab jab is forbidden.

Jab jab like Jaden are fearsome— with the magical ability to steal the souls of their victims.

He looks like midnight, his dark skin speckled with starlight— He smells like hot iron forged with fire like mine. He is ancient magic too.

I close my eyes and my skin suddenly feels like it’s actually actually becoming silk under her touch—

My skin glows like embers, like stars.

it’s better if a boy likes you more than you like him.

Except the Black part of me might as well be a dream—an unknown thing in the shape of an absent mother that haunts me at night.

Dad hates this neighborhood. Whenever he steps off our (historic landmark) block, he complains about the trash, the noise, the people, so I call him a racist— Dad hates my school. When I decided to leave my almost all-white private school to apply for a public performing arts high school and he tried to talk me out of it, I called him a racist—

With all the African and Caribbean art we have around the house, it’s clear that Dad loves Black culture. But when Micah first came over, he said, “It’s like the British Museum up in here.”

And each school is a different world— Like, I swear I have to walk through a battlefield just to get to the fourth floor where BPAA is. Micah goes to one of the other schools. I met him while walking home.

He is the entire Caribbean all in one soul. I am a cultural artifact in a museum in a landmark home in the middle of the hood. Two different worlds—

Today, I am the sun and the sky.

And everything today will be soft clouds and sunshine. And I will dance like the universe is watching.

On the islands, we are much more poetic with our insults. Callous words are wrapped in metaphor. Profanity is sprinkled with sugar so the words are not so sharp; so the wounds are not so deep. Here, words are machete blades. They don’t slice or cut. They chop.

And fill my belly up with this fast American food. Not a healing balm for my hurt soul.

“We are not on the islands anymore, Madame Jean-Pierre,” I say. “You cannot make these accusations.”

At times like this, I wish we could call on our monstrosity for protection— but we are always at the mercy of nature.

Mummy is wearing the same dress she left in. But something is different about her. She looks as if she found what she was looking for, and maybe it is money. More money. “Take your garbage and leave!”

Madame Jean-Pierre narrows her eyes at my mother, then she goes over to the mortar and kicks it. It drops to the floor with a hard thud, and it rolls to Mummy’s feet as if for protection.

that hell is here in this new country. Every day, someone is made into a monster.

“Mummy, we should separate work from life so this does not happen again. I am tired of running.”

We can destroy and we can heal. But I am still learning how to perfect my cooling touch.

He calls it chivalry. I call it embarrassing.

Lougarou in Haiti. Soucouyant in Trinidad. Old hag in Jamaica. Same shit, different island. My mother believes in those stories. Her church friends are always accusing somebody of being a witch or a shape-shifter or whatever—

While he thinks they’re just superstition, my father believes they’re science.

And in a few years’ time, I traded in my secondhand T-shirts for my own uniform. Girls like me start working at the resorts as early as age twelve.

We can never know who is family, and who is enemy; who is monster and who is prey, until night comes; until the new moon—

“they like to destroy things in order to understand them. They do not know that magic belongs to the soul and not the mind.”

Genevieve flutters around the house like a butterfly, leaving clothes and towels everywhere; picking at her food; complaining about the heat, the cold, her hair, her face, her skin—