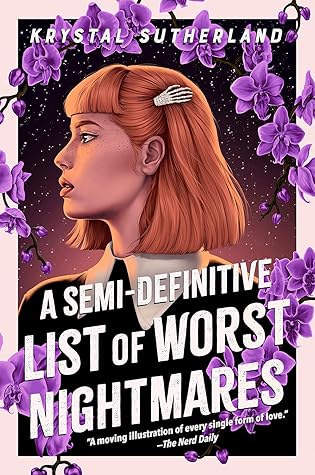

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 17 - February 25, 2021

“Listen, asshole. We’re not dying. We have shit to do.”

When you have anxiety, you don’t really get to have deep breaths. Your ribs are too small to let your shriveled lungs expand beyond half their size.

“I wouldn’t lie there if I were you,” Jonah said. To which she replied: “Can I live?”

“You know, I’ve been thinking about you ever since I robbed you this afternoon,”

And that was how she got stuck with the responsibility of caring for Jonah’s stupid cat, who he named Fleayoncé Knowles. Naturally.

“I’m sorry I wasn’t there, but it wasn’t my choice. I was eight. It wasn’t my job to protect you.”

to an anxious person, logic didn’t matter.

Jonah didn’t cross 50. Lobsters off the list now that it had been conquered. Instead he tore it off and shoved the little bit of paper in his mouth and chewed it up and swallowed it.

Esther pictured herself as she knew her classmates saw her: ugly and imperfect and too weird to be allowed.

There, sitting solitary in the middle of her securely padlocked locker, was a single raspberry Fruit Roll-Up.

“I’ll do it on one condition.” “Okay.” “Tell me how you got into my locker every day.” “A magician never reveals his secrets.” “Good thing you’re a pickpocket and not a magician then.”

If you didn’t let people get close to you, they couldn’t hurt you when they left. So that’s what she’d done, and what she intended to continue doing now.

Death was looking for Esther Solar; as long as she never dressed as herself, she hoped he’d always have trouble finding her.

“What are you gonna do, draw me like one of your Optimus Primes?”

If something was once true but now wasn’t, was it ever true?

What other beautiful things had fear been hiding from her?

darkness could live in a person and eat them from the inside out.

And I am being serious. Go on a date with me.”

“Look, fearless people are stupid, ’cause they don’t even understand what fear is. If I was fearless, I’d jump out of a plane without a parachute, or eat your mom’s cooking again.” Eugene laughed at this. “Yeah, there we go, he knows what I’m talking about. Point is, you gotta be scared. Fear protects you. You gotta be scared right down to your bones”—he touched his fingertips to her collarbone—“for bravery to mean anything.”

Everything you want is on the other side of fear, she reminded herself. What was fear hiding from her this time?

“I love you. Don’t ever forget that.”

“Sorry, can’t,” said Esther sleepily. This close to him, she felt the sudden desire to press her lips to his cheek and wrap her arms around his neck, which was not a desire she was used to feeling for anyone. “Why not?” “I have a date.” Jonah grinned about as mischievously as she’d ever seen him grin. “See you on Sunday.”

“It’s what’s in the corn that’s scary.” “What the hell is in the corn?” “Children. Crop circles. Scarecrows. Serial killers. Tornadoes. Aliens. Seriously, cornfields are messed up. They may actually be the epicenter of all evil things.”

knowing logically that she was in no real danger but unable to shake the certainty that death was imminent.

“Do you want to go on that date now?” she asked him, and he said yes, so they did.

“I’ve been trying to woo you since elementary school. You’re just too distracted to notice. You think I’d reupholster a couch for just anyone?”

Esther had no illusions about who or what Jonah was: he was a pickpocket, a skilled petty criminal, an underage drinker (then again, so was she), a public nuisance, and also—undoubtedly—the very best person she had ever met.

Nobody is going to care.” “I care.” “Too much. About too many things.”

Why? So many reasons. Because she wasn’t good enough. Because something inside of her was rotten and broken and unlovable. Because Jonah would figure this out eventually, and why bother starting something if the end of it was inevitable?

Sometimes it was better to not get what you wanted. Sometimes it was better to leave beautiful things alone for fear of breaking them.

The hurt in his voice killed her, because pain was a language she’d learned to speak well, but she couldn’t give him what he wanted. Couldn’t give herself what she wanted either.

“Let me get this straight. As soon as you come close to failing at something, you decide to never do it again?” “Exactly. Then I can feel really, really good about never having failed at anything. It’s all perfectly psychologically healthy. I’m a genius.”

The driver in the car behind them leaned on the horn again. Jonah rolled down his window. “You want me to come back there? I will come back there, asshole! She’s learning!”

There were only so many times you could have panic attacks in front of people before they wrote you off as a lost cause. Too fragile. Too much hassle. Too painful to be around.

Maybe if she was sexy, or confident, or her skin wasn’t covered in a minefield of freckles, then she could justify being crazy and broken and weird. As it stood, there wasn’t anything alluring enough about her that she could imagine making him want to put up with her bullshit for any great length of time.

People got tired of mental illness when they found out they couldn’t fix it.

“I don’t hate her for what she’s become. I want to, but I can’t. I love her too much. That’s the problem. That’s what’s wrong with love. Once you love someone, no matter who they are, you’ll always let them destroy you. Every single time.” Even the very best people found ways to hurt the ones they loved.

Anxious people always thought the world revolved around them, but knowing the truth didn’t make it any easier to stop believing the lie.

“Yeah, I did. Told her about you being picked on at school, because it upset me. She sat me down and read me that quote, the one that says, ‘All tyranny needs to gain a foothold is for people of good conscience to remain silent,’ then explained what it meant and what I needed to do. I sat with you for the first time the next day.

“One day,” he said, “everybody’s gonna wake up and realize their parents are human beings, just like them. Sometimes they’re good people, sometimes they’re not.”

Perhaps falling and remaining in love with people, even if you didn’t want to, was not the great disaster she’d always imagined it to be.

Not for the first time, she wished that his injuries were more obvious. That whatever swollen, infected thing inside his head that made him feel this way could be seen, could be sliced away, could be stitched up and covered with a bandage like any other wound.

She hated not just that they were broke, but that everything they touched seemed to turn sour and curdled, breaking to pieces in their hands. She hated their life. She hated the bits of it they’d chosen for themselves and the bits of life that had fallen on them like dandruff, unpleasant and unwanted.

she wasn’t enough—strong enough, smart enough, brave enough, enough, enough, enough—to save him.

How could you save people who were drowning in themselves?

All along she thought he thought he was saving her, but she could see it now; they had both, each of them, been saving little bits of each other.

“You take me on some really weird dates.” Esther tried to suppress a smile; you had to admire his perseverance. “We are not dating.” Jonah chuckled. “Why do all my girlfriends keep saying that?”

Each one of them had once been a human being. The aggregate of all their happiness and sadness had been immense. The memories they’d held in their collective heads could have overloaded all the servers in the world. That severed foot used to be a living, breathing, walking, real human with thoughts and memories and emotions. That slice of brain had once stored the cumulative thoughts acquired over decades that had made the donor the person they’d been. So much work for nothing. That a living thing should be there and then gone just seemed so impossible. So impractical. So . . . wasteful,

...more

Esther understood the first law of thermodynamics, that nothing was created or destroyed and all the little bits and pieces that made up a human would be redistributed elsewhere when they died, but where did the memory go? The joy? The talent? The suffering? The love? If the answer was “nowhere,” then why the hell did we even bother? What was the point of these fleshy globs of consciousness that ate and drank and loved and rose from cobbled-together bits of the universe?

pus would seep from an infected wound. And maybe it was true. Maybe Death did leave his mark on Esther’s grandfather, but all he was to her was a good and gentle man left halfway broken by the terrible things he’d seen and a terrible truth that had left him unable to sleep at night.