More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

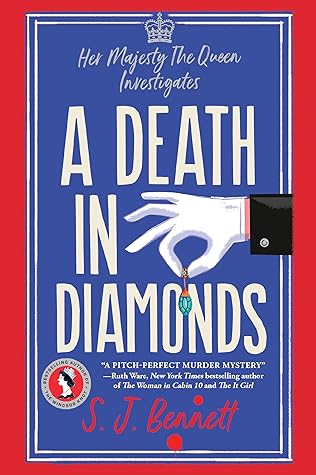

S.J. Bennett

Read between

January 21 - February 18, 2025

But, without going into detail, it was a crime requiring two people to, um, subdue the victims. There’s no evidence he had an accomplice, or indeed a motive. It has since been established that the house was used entirely without his knowledge for illicit assignations.’

If the murders happened when the police think they did, then the dean either just missed the killers, or slept through the whole thing. Why didn’t he notice that the flowers he had bought for his bedside the day before were missing? Or that the back door was unbolted? Or – most importantly – that the door to the second bedroom, opposite his own, had been left partially open, as the charlady found it the following week?

The Clement Moreton she remembered was a sharp, quick-witted man, as you had to be if you were going to beat her mother at canasta, which he had done more than once.

‘Anyway, Inspector Darbishire strongly suspects a link with a London gang. He’s already found out that Perez was consorting with some dubious characters. He was from Argentina, ma’am.

As I say, it’s best if I don’t go into details, but Perez was attacked first, almost certainly, and Fonteyn killed as a witness. Perez was taken by surprise in the, um, bedroom and left where he fell. The knife was applied afterwards, in some sort of vengeful act. Or possibly as a message.

There’s no sign of any bullet, casings or damage that might have been caused by one.’

‘There was an anonymous phone call, later on that Monday morning. It came from a public call box on the King’s Road. A muffled voice, telling the operator that there had been a terrible accident in the mews. But the operator didn’t catch the full address, and the police went round and found nothing. They’ve only recently realised it might be important. In the meantime, the focus has turned to Lord Seymour, the Minister for Technology.

He’s given a statement explaining that the diamonds were stolen from the safe at his home.’

Fortunately, he has the prime minister and half the Cabinet as his alibi. He was with them at a dinner in the House until after ten thirty on the night of the thirty-first. He went straight home, where the servants and Lady Seymour can vouch for him. As alibis go, it’s a pretty good one.’

Seymour’s well regarded. Mr Macmillan himself has said he’s destined for high office.

He had put on his best suit today – of the two that he possessed – and his favourite tie. It was navy blue and slightly narrower than was traditional. He liked to think it gave him a certain air. Woolgar, needless to say, had traces of egg on his lapel which he tried to brush off with one hand when they were pointed out to him.

When Darbishire and Woolgar knocked at the polished front door, it was answered by a butler who took their hats and showed them upstairs to a book-lined room, lit by a large Georgian window, with the promise that the minister would be with them shortly.

Seymour had inherited a family business and a small property empire, which he had made bigger by investing in car parks after the war, buying up old bomb sites and exploiting them in ways no one else had thought of.

Darbishire expected someone lofty and dismissive, but the man who arrived two minutes later was smooth and smiling, warm in his handshake, keen to look you in the eye.

Seymour crossed one immaculate, pinstriped leg over the other. His face bore faint traces of a suntan, his jowls a hint of good living– but he’d retained much of his youthful attractiveness.

Richards has been with us for twenty years. He would certainly lie without a second thought, if he believed it was in my best interests. My wife, on the other hand, is pure as the driven snow. She wouldn’t lie if her life depended on it, to save me or to sink me, but you have only my word for that.’

On the other hand, Seymour could easily have hired someone else to do the dirty deed while he was at the House.

There was a flicker in Seymour’s eyes, and Darbishire saw him hesitate and calculate. It was the first time he’d done this. He inclined his head.

Seymour lifted a Venetian oil painting of the Grand Canal off its hook, and indicated the safe set into the wall behind it. It was about eighteen inches by twelve, with two brass handles and a central keyhole set into the door. Darbishire had seen hundreds like it.

As I said in my statement, I didn’t see the description of the diamonds in the gutter press – we don’t read that sort of thing.

‘When exactly we were burgled, we don’t know, but we’ve had workmen in and out. My wife’s been redesigning the drawing room and bedrooms.

I keep one key on my fob and the spare at the bank. Neither was used.

‘You said in your statement that the last time you looked in the safe was on the twenty-fifth, six days before the murders.’ ‘Yes. I needed some paperwork.’

She was going to wear it to her party.’ ‘But why a tiara?’ ‘Isn’t that for duchesses and the like?’ Woolgar butted in. Darbishire had been searching for a polite way of putting it.

Until now, the inspector had been far from convinced by the minister’s stated devotion to the wife he regularly cheated on with prostitutes.

He had an air of authority about him. Older than her: in his forties, probably. His hair fell into a cowlick that he brushed unconsciously from his face. His skin was freckled, like hers, and his eyes were tired. There was a certain cragginess to him.

‘A chap got in touch at the club. Said he knew someone – I could have sworn he said John – who needed helping out. I was happy to oblige. We used to have guests often, but we’re not in town much these days. At least …’ He paused. ‘I am, but my wife isn’t. Dashed awkward.’

He’d been thinking aloud, but they both knew that the first rule of Longmeadow was that you didn’t talk about it.

Darbishire needed open sky. He was not quite forty, but he was starting to feel old.

Under further questioning, the charlady at Cresswell Place had confirmed exactly what he suspected about the mews house, which was that it was one of several posh locations used for the assignations of some Raffles VIPs who didn’t want to risk being spotted in a hotel. These locations used to be kept empty, she said, but the landlords started getting greedy and looked for tenants who might want the place on a Monday-to-Friday basis. One room would always be set aside and kept pristine for Saturdays and Sundays, without the renter’s knowledge.

because people don’t always do what you expect them to do, do they?

tenants were supposed to call and check if they could stay over on a weekend, because it was written into their contracts that they couldn’t, and technically they weren’t paying for it.

The dean had in fact made such a call. But the office girl at Raffles said that it wasn’t a problem, because they had nobody booked that night. Beryl White and Perez were not supposed to go there. Which raised, once again, the question of the keys.

The Raffles agency and the letting agency needed to talk to each other to make this precarious arrangement work.

‘I apologise for Miles. That was unpardonable. He can be a brute sometimes, but he doesn’t mean it. He’ll come round eventually, when he sees how indispensable you are.’

It was Tony Radnor-Milne, not Jeremy, who stood in the hallway. Joan instantly saw the likeness, but Tony was much taller, clearly the older of the two. He was clean-shaven, with the same long face and wavy hair as Jeremy, although his was flecked with grey. His fur-collared coat suggested a very expensive tailor and there was a swagger about him, as if he was usually the most powerful person in the room.

She couldn’t hope to compete on the looks front, but at least her outfit was on a par with theirs.

When her father had first come to London, he had encountered signs in bed-andbreakfast windows saying, ‘No Blacks, no Irish, no Dogs’.