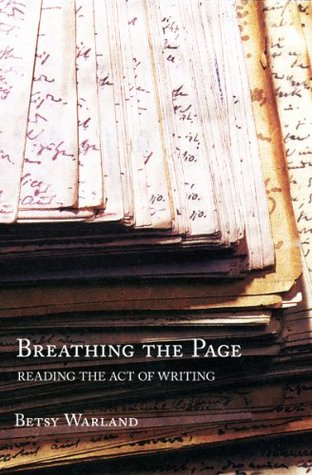

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

read only the first page of each. Which first pages excite and intrigue you most? Which ones make you eager to continue reading? Once you have found a number of such first pages, determine how each author drew you in. Which strategies used by these authors appeal to you most, give you ideas for the first page of your own narrative?

All prose narratives, whether fiction or creative non-fiction, are constituted or reconfigured from various fragments of memory;

In contrast to fiction, creative non-fiction begins with an overwhelming array of memories, observations, documents, research, and, not infrequently, a cast

After you have written this coma story, write into a comma by doing one or more of the following: Insert a comma before the first word of the story and write whatever comes to you into that comma. Insert a comma anywhere in the story where you know or sense there’s more to tell — including the censored or dismissed — and write into that comma. Delete the period at the end of the story and replace it with a comma and write into that open space. It may be productive to set a timer and allow yourself to do a free-writing exercise for five minutes without pausing or judging it.

At this point, should the camera (the reader) be in close-up, mid-range, or panorama? Does the camera jump around? Does it remain pretty much in the same position?

The writer figuratively holds up a billboard that states things in a pedantic fashion.

Take two pages that you feel dissatisfied about and identify the overriding depth of field position. For example, maybe it’s mostly historically distanced. Shift the focus, rewrite it in close-up, and see what happens.

Heightened awareness of how to score the resonant space of each poem, essay, or chapter opens up a mutually shared space in which the reader and writer are free to absorb what is being articulated, to discover our own emotions and illuminate our thoughts.

ask students to draw an overhead diagram of how they typically occupy a room in public space. Again, there is puzzlement, but their curiosity is piqued. I specify that it must be an enclosed space in which there is no pre-assigned seating. It could be a café, a bus, a theatre, a classroom — any kind of public room that they frequent. I instruct them to mark the location of doors, windows, furniture, and significant objects such as large potted plants, as well as where other people are located, and then to indicate where they routinely sit or stand.

When discussing their diagrams, writers often see how their most habitual manner of occupying and not occupying public space influences how they routinely inhabit and refuse to inhabit the page, regardless of what each narrative requires.

Because a poem’s very form acknowledges both what can be said or known and what can never be said nor known, poetry may be as close as we come through language to the sacred.

When hearing a poem in a language from a culture we do not know, full comprehension remains out of reach. Unlike prose, however, a poem’s signalling power is nevertheless operative. Poems transmit the sentiments of their sonic territories via each poem’s unique set of emotive tones and narrative energy, and we are affected on a cellular level. A poem speaks to us in the same way that foreign music and visual art get through to us.

Poetry is a riptide where language and silence negotiate one another’s equally powerful currents. Ultimately, sound (language) and silence (scored space) are the same thing: emphasis and meaning.

The best way to begin is to try checking your breathing against your narrative’s intrinsic form. Read aloud two pages of your work and pay close attention to how your breathing corresponds to the narrative’s content. Are you running out of breath in an area where the narrative is tranquil? Is your breathing erratic where the narrative is taking you through some awkward,

He was shocked to discover that his journals contradicted his memory about very significant events. For example, he was certain that he had driven his lover to catch a plane and initiated their breakup on the way to the airport. In his journal, it was she who initiated the breakup on the way to the airport. I suggested to him that apparent action isn’t always the most authentic action: he may have passively orchestrated their breakup (and this is the intention he remembered) though, on the surface, it was his lover who broke up with him. This is an example of where our poetic licence as

...more

The writer’s body is the site of all memory storage, research, imagination, processing, and selection: it is the conduit from which the narrative emits.

An intriguing way to explore how you might better maximize form = meaning is to take an excerpt, short piece, or poem and re-score it into three different forms. Allow the subtleties, subtexts, and tonal energy embedded in the writing to cue you as to options you have in rescoring it into three diverse forms/ versions. Don’t be restricted by the pre-existing formal approach: try anything that frees the narrative to occupy the stage (page) in its full power.

When form is not appropriate, your narratives are: Predictable; not surprising Resistant to being worked with Unclear in focus and intention Over-simplified Inaccurately paced, sequenced, proportioned Subject to being misread

Lacking embodiment, the reader is not deeply located A slog to write When form is appropriate: Your narratives surprise you, even frighten you You are fully present, embodied, keenly aware you are on the scent You have a conviction that the narrative in its own right is compelling You occupy a clear, authentic voice You trust the narrative and images to unfold of their own logic The form begins to collaborate with you, helping you generate the narrative

One way I see the whole territory of a narrative is to spread its pages out as much as possible. If your narrative isn’t too long, spread it out on a large floor or tape all its pages on the walls for a few days. If it is a book-size narrative, then I spread it out section by section or chapter by chapter and record what I discover with each portion as I go. What impression does it give you visually: solid as a wall, fractured, porous, static, chaotic, undulating? How does this visual experience of the materiality of your narrative relate to its content and spirit? I allow myself to move in a

...more

Another revealing way to check a narrative is to track its tangents. Tangents are areas where the narrative appears to swerve off topic or appears to linger too long on something that seems incidental or insignificant. Tangents, however, can be where one of the most compelling aspects of the narrative resides. This possibility is overlooked more often than creative writing teachers or books on creative writing acknowledge. So, pause and enter a state of curiosity before hitting the delete key.

if your narrative is long, such as a novel or memoir, mix up the order or sequence: juxtapose them to jar yourself out of your perceptual gridlock. Also try pulling out sections — all one character’s dialogue, all the scenes happening in secondary settings, all seemingly minor themes — and determine how well these coincide with the narrative’s intentions.

I know that it is absolutely necessary to assemble these different narrative slices physically in different piles or areas. Providing them with their own discrete physical environments is crucial, because my body often knows what the narrative’s body requires

A writer recalls each writing room with an intimacy that rivals the recollection of each lover.

Write the narratives that hunt you down: the ones that surprise and terrify you, the very ones that you often would have preferred not to write! Take risks in content and form. Wake up to your habits of craft and ways of working with narrative and relentlessly question the suitability of using them with each narrative you write. Accept that each narrative has its own specific requirements and that what you brilliantly figured out for your previous narrative often does not suit the ones that follow.

Give readings as much as possible for this gives you a concrete sense of where revisions are still needed as well as where your audience responds positively to your narrative.

Put your trust in the act of writing itself: the timelessness of it; the endless intrigue of it; the rigorousness of it; and how this nourishes you because everything else about your life as a writer is secondary (at best) in comparison.

As a profession, for the majority of us it is an illogical pursuit, offering little financial reward and uncertain reception once we have published a manuscript. Yet many people dream of becoming a writer — more than they do about any other creative occupation

As writers, we must learn to be profoundly self-responsible. There is no one else who will take care of our practical needs as a writer or do our time management for us. Writing is often said to be the most solitary of the art forms; correspondingly, nearly everything in our writing life depends on one thing: ourselves.

It is not unusual for us to think that we have finished a manuscript several times before we actually have.

Few of us are affluent authors living off advances and royalties from bestsellers. If an author’s books are not routinely on academic course lists nor of interest to the commercial market’s trends, royalties provide a partial income at best. Increasingly, writers are self-publishing via their own websites and blogs. As a writer builds readership, a sizeable income can be made via sales of their books, chapbooks, cds, and speaking, teaching, consulting, and mentoring services.

It is paramount to remember that it is the writing itself that is giving the reading (not our persona). As we read word by word, we become the narrative’s single-focused, primary listener. The encounter is between the narrative and its listeners. During this encounter, I can also listen through my “third ear,” particularly when reading works-in-progress. This is a crucial part of my writing process. As I read, I can hear where I have erred from the veracity, tone,

When our narrative becomes our companion, the forcefulness of the insistent narrative sustains us through debilitating doubt. Then, when we have finished the narrative, that same force will fuel us to find a publisher so that our readers, too, can encounter this narrative’s particular force.

As writers, we must also do market research and be able to speak knowledgeably about what other books are similar to, yet different from, ours, how positively they were reviewed, and how well they sold.

If you have worked in-depth with an author on your manuscript, inquire if that author feels your manuscript is ready and is of enough merit for that author to recommend it to a publisher.

The value of this exercise is that at any given time — and it is instructive to do it from time to time — it precisely delineates what aspects of our writing lives are working well and what aspects are frustrating us. Most important are the first and inner circles: “How do I feel when I am immersed in writing?” and “How do I feel about the act, or process, of writing?” This is the core: what we must protect and nourish above all else. We must not allow other closely related, sometimes disheartening, concerns such as “How do I feel about myself as a writer?” or “How do I feel about publishing

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“Between page and writer is a magnetism more compelling than any other relationship.”