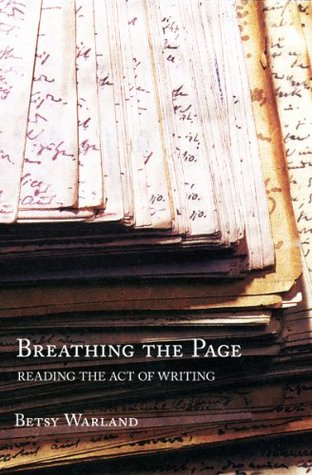

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The act of reading is an act of belief.

The use of well-timed humour or conflicting perspectives can assure the reader that your narrative has been well considered.

Pacing of the narrative is another manner by which to signal that the narrative will not be in the reader’s face — that the narrative itself understands the circuitous nature of storytelling, whether it is a poem or a novel. Pacing also acknowledges our human need for time to absorb and reflect.

It is not unusual, however, for writers to be unclear about what the narrative’s predicament is until we are well into the first or subsequent drafts. Once we do recognize it, we must return to the opening of the narrative and revise it to accurately cue the reader.

As writers, it is crucial to keep in mind this notion of the scene of the accident in order to render points of view and perception with integrity, accuracy, transparency.

It is always a risk to transform the private and the intimate into the public.

Heartwood is the narrative’s original germinating seed. It is the source from which the narrative authentically and inevitably materializes as the core of a tree’s rings of growth. As a writer, you need to know what the heartwood is in each narrative to ensure that your writing finds its authentic, vital expression.

What writing is still to be done? What substantial revisions and deletions must be made? Why am I writing this narrative?

Heartwood most often reveals that the narrative is not quite about what you thought it was about.

believe every narrative knows where it is going; it knows what it is about.

In prose, this sounding out is also vital to writing authentic dialogue. Tone, transitions, indicative pauses, distinction of characters’ voices, pace — all can be assessed more accurately through listening.

Sometimes unintentional repetition is attempting to flag you — alert you to a place in the narrative that requires more “unpacking” or lingering.

Habits of repetition we are extremely resistant to changing are the very ones we need to explore and change.

“to read is to enter into a profound participation, or chiasm, with the inked marks on the page.”2

When reciting the alphabet out loud, the vowels’ free passage of breath opens outward — then crests periodically — between the accumulating waves of consonants’ partial or complete obstruction of the air stream. The alphabet replicates our lungs’ movements — breathing itself — as air animates voice, the alphabet animates page.

Breath is life. If breath is believed to be a manifestation of the deities, vowels may be the vestiges of divine speech. An infant’s early word-sounds are nearly all vowels. Our final dying word is often a vowel. It is with the vowel we come into this life from elsewhere. It is with the vowel we leave this life for elsewhere. Throughout our life, Latin, vowel, vox, v...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When we recognize the trance we fall into, we can then awaken ourselves from the coma story’s grip on our narrative.

One way to think about proximity is to think of it cinematically, to equate where the camera locates you in a film with where you locate the reader at any given time in your narrative.

Then develop the habit of routinely asking yourself: At this point, should the camera (the reader) be in close-up, mid-range, or panorama?

Proximity shapes meaning.

To be true to the story often requires considerably more writing or revision than we had imagined — or want to undertake.

When, as writers, we commit ourselves to writing a poem or prose piece, we must rappel down the cliff of our verbal vertigo.

It is important, however, to reassure ourselves routinely that no effort is lost nor writing wasted during the scaffolding stage of inscription.