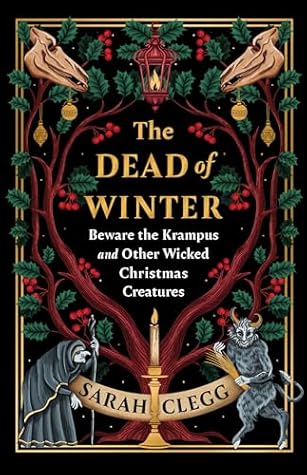

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Sarah Clegg

Read between

March 24 - April 8, 2025

Perchta, a monstrous witch with an iron nose, who travels house to house every Christmas leading a cavalcade of the dead. If she finds a child who hasn’t done their chores she slits open their belly, pulls out their guts, stuffs them with straw, and then sews up the wound with a ploughshare as a needle and a chain as thread.

There’s Krampus, a hideous, towering demon with enormous horns who beats children with a switch or steals them away, and who rampages through Germany and Austria every 5 December.

Iceland, there’s Grýla, an ogress who comes down from the mountains at Christmas and is inclined to eat her victims, popping them into a giant stew while her murderous cat – the Yule Cat – prowls at her side.

In France, there’s Père Fouettard – Father Whipper – a butcher who had kidnapped, murdered and tried to pickle three young boys, before he was stopped by St Nicholas. As punishment, according to the legend, he was forced to accompany St Nicholas for the rest of eternity, a looming figure lurking...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Year Walk, or årsgång, a tradition that has been attested for centuries in Swedish folklore, which tells how a walk taken before dawn on Christmas Eve, without eating or drinking, without talking to anyone, without looking into a fire, will show the future. More specifically, it should show me shadowy enactments of the burials of anyone who will die in the village this coming year.

Showing fear is one of the ways to summon these monsters – or stop the magic altogether. Laughter will also break the spell, and though someone might be unlikely to burst into giggles at the sight of an unhappy revenant or a horrifying pig, there is a Year Walk story in which two tiny, farting rats appeared in the path of the walker, causing him to laugh and forgo his chance of seeing the future. No farting rats, walking corpses, or multi-eyed sows appear in front of me this morning, but no ghostly funeral processions cross into the graveyard either.

explicit cross-dressing is also associated with Carnival, and I encounter plenty of women wearing traditionally male outfits, and dresses worn with beards. There’s even a greeting ‘Siora Maschera’ – ‘Ms Mask’ – that can be used for anyone – man, woman, rich, poor – since anyone could be anyone behind a mask.iv

Saturnalia – the feast of the god Saturn – started on 17 December,

According to his near-contemporary Seneca, it was a time when ‘licence had been granted to public self-indulgence’, and everyone was ‘drunk and vomiting’,2 giving in to excess and luxury with wild abandon. People gave gifts, but they were often gag gifts, so that the emperor Augustus himself was apparently giving people ‘nothing but hair, cloth, sponges, pokers and tongs, and other such things under misleading names of double meaning’.3vi Normal societal rules were suspended, so that gambling, usually illegal, was allowed and hierarchies were switched and swapped, so that during the Saturnalia

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

king of Saturnalia (and used the occasion to humiliate his step-brother by forcing him to sing in front of a drunken crowd). According to Lucian, writing in the second century, Saturnalia was a time of: Drinking, noise and games and dice, appointing of kings and feasting of slaves, singing naked, clapping of frenzied hands, an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water.4 This loss of rules and hierarchy supposedly recalled the ‘golden age’ of Saturn, when no one was a slave, no one held property, and ‘all things were common to all’,5 a brief restoration of

people lit fires scented with saffron, wore nice clothes, and weren’t supposed to argue, and if all that wasn’t thrilling enough, there was also a stately procession of the new consuls to the Capitol. But the spirit of Saturnalia only had to slip forwards by a few short days to spill into the Kalends celebrations. By the fourth century AD, the Greek writer Libanius was describing how Kalends was a three-day festival that – like Saturnalia – revolved around gift giving, drunkenness and excessive eating, along with a shifting of normal rules and hierarchies so that slaves could be lazy, or even

...more

audience of slightly baffled tourists. It’s even more prominent in other Carnival celebrations around the world, and often makes a political point – in Germany in 2024 in the Cologne Carnival parade there were floats made to mock Donald Trump and the German far-right party, while the New Orleans Carnival saw parades that incorporated protests for Palestine.

And the figure who ended up ushering some chaos into the church calendar was, surprisingly, Herod.

The 28th of December was the Feast of the Holy Innocents

in the mid-twelfth century, the Feast of Fools was established. This new celebration seems to have started in France, and stemmed from a 1 January feast day, the Feast of Circumcision (celebrating the circumcision of Christ eight days following his birth), which had also become the day that the subdeacons – the lowest of the clerical orders – were honoured. It might well have begun in a fairly calm manner, but being on the same date as Kalends and celebrating the most junior clerics was a recipe for turning social hierarchies on their head and it wasn’t long before it was all getting a bit out

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

church might have wished for the Twelve Days of Christmas to be entirely devoted to a celebration of Christ, the unruly mayhem continued, with its highpoint often coming on Epiphany or Twelfth Night (hence Shakespeare’s play of the same name, which is full of drinking, pranks and cross-dressing). And a new practice was emerging – or, at least, an old one in a slightly different guise. Starting in the late medieval period, the kings of France had begun electing their own Christmas rulers to preside over the celebrations – the kings of Saturnalia and the Popes of Fools made

It’s not a coincidence that the word for a Carnival mask – ‘larva’ – also translates as ‘ghost’. Seeing the figure lingering in the darkness, in that silent, empty night, the white face glowing in the street light, feels like a haunting.

it’s St George who fights a Turkish Knight instead of King William fighting Little Man John. The Christmas play in London on Bankside uses the same names, as does the one in St Albans. Elsewhere in the Cotswolds there’s a variant play with Robin Hood; in Scotland the St George character is called Galoshin. Sometimes, the murderer is simply called ‘Slasher’. In some Irish variants, it’s St Patrick against the evil Oliver Cromwell. Beelzebub hops through the majority of them, collecting money from the audience, Father Christmas almost always announces the proceedings, and in most cases the

...more

often the players dress as their characters, St George wearing a cheap Crusading-knight costume from Amazon; Robin Hood in a feathered hat and holding a bow and arrow.iii But they are all, to a one, disturbing to watch, dancing with devils and centring on Slashers and murderers, and all of them have the feel of a ritual that taps into something utterly ancient, something with a profound significance that is now all but lost.

earlier tradition of going door to door has numerous different names (including, unhelpfully, mumming), but the most common one (and the one I’ll be using here) is ‘guising’.

Unlike the death-and-resurrection mummers play, dated so securely (and so disappointingly) to the eighteenth century, Christmas guising is over 1,500 years old: wearing costumes and masks was associated with Kalends from at least Late Antiquity. Alongside the clergy complaining about topsy-turvy social disorder, there were just as many bemoaning that people were dressing up and going from door to door demanding food, drink and money. In the mid-fourth century AD, Bishop Ambrose of Milan recorded a tradition ‘of the common people’, where on 1 January they disguised themselves as stags. His

...more

In 1348, people in the court of Edward III dressed up as animals over Christmas. In the earliest sources from Iceland, meanwhile – that is, in the mid-thirteenth century – there are hints of a house-visiting tradition featuring men dressed as the ogress Grýla. Even Bishops started to get in on the fun – in 1406, the Bishop of Salisbury enjoyed ‘disguisings’ in his manor during the Twelve Days of Christmas. The Boy Bishops, as well, went door to door demanding treats, mirroring the actions of the guisers even if they weren’t dressed as monsters themselves. Christmas guising may even lie at the

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The word ‘wassail’ first appeared in the eighth century in the poem Beowulf, and seems to have been a toast (at the very least, it was a shout that should echo through courts and begin the revels of warriors). By the fourteenth century, we have mentions of communal drinking bowls that could be passed person to person with cries of ‘wassail’ and ‘drinkhail’ and an exchange of kisses. And while cheery toasting at mass get-togethers sounds very Christmassy, it was only in the sixteenth century that wassail bowls are firmly placed in the Christmas season, appearing at a Twelfth Night party in

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

as well – the Blackthorn Wassail held by Newton Court Cider is another orchard wassailing, with plenty of Mari Lwyds in attendance, monsters that have, late in life, turned to driving out evil rather than just causing it. On Old New Year (13 January)

According to tradition, when the Mari party calls at the door, you might just be able to avoid letting them in – as long as you’re a good enough poet and can hold a tune. Right now, standing on the threshold of the Maestag Corner House, Gwyn Evans breaks into song – a beautifully rich baritone that resounds through the little pub. The words are in Welsh, but a handy translation has been provided in a little printed leaflet I’ve been given:

Well here we come, Harmless friends, To ask permission To sing. This is the beginning of a ‘pwnco’, a rhyming call-and-response game that was once carried out between the Mari party and the residents of whatever house they’d chosen to approach. If the householders wanted the ghostly horse and its retinue gone, they’d have to outwit them in the game. We do have some surviving records of responses to the Mari Lwyd. Normally, they attack the rhyming and singing abilities of the Mari party (‘The dogs and the cats are retreating into the holes on hearing such voices’ or perhaps ‘The kettle and the

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

pole about ten feet in length, and a string is affixed to the lower jaw: a horse-cloth is also attached to the whole under which a member of the part gets, and by frequently pulling the string, keeps up a loud snapping noise and is accompanied by the rest of the party, grotesquely habited, with hand bells, they thus process from house to house, ringing their bells ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

This might be an account of any Mari Lwyd (barring the astonishing length of the pole), but here in England it was called a Hoodening – a term likely...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

was hooded by the sheet. And like the Mari Lwyd, the hoodening tradition continues to be enacted, normally in Kent, Yorkshire and Derbyshire – although most, now, use wooden horse heads rather than skulls.viii By all rights, the wooden version should be a lot less terrifying, but there is something utterly, intentionally unsettling about every one of the hoodening heads. The hooden horse from Walmer Court, dating to the 1850s and held in the Deal Museum, is a perfect example. Decorated with red and white rosettes, and with a trio of bells perched on its head, it’s made from two flat rectangles

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

the Vienna Folklore Museum is a yellowing wooden goat head on a pole. It has flapping black ears, short, curved horns, wide black eyes and an enormous, gaping, snapping mouth, lined with sharp little rows of carved wooden teeth. The jaw is rigged so that it snaps closed when the performer, holding the pole and hidden beneath a sheet, pulls on a thin piece of string dangling from the back of the monster’s head. This creature is called a Habergeiß, a name almost certainly related to goats (‘geiß’ is the Austrian for ‘goat’) and it can be found prowling the streets and snapping at the unwary in

...more

hides under a sheet (although the sheet that covers the Corlata can often be extremely brightly patterned – one photograph from 2010 shows it covered in brilliant flowers). In North-East Germany there’s the Klapperbock (the snapping buck), in the Italian Tyrol there are the Schanppvieh – snapbeasts (although these normally appeared at Carnival rather than Christmas). In Switzerland there’s the Schnabelgeiß, the ‘beak goat’, which looks like all the other goat monsters except that the snout narrows to a point, to take the form of a beak. In Finland and Sweden there are the Nuuttipukki, more

...more

St Lucy, who, with her saint’s day in the depths of winter and a name derived from the Latin word for light, has come to be thought of not just as a saint, but as the light coming back into the winter darkness.ii

Lucy ceremonies like this take place across the Nordic countries, some just as magnificent, others far more lowkey. The ceremonies started in the 1930s in Sweden, but the tradition of girls dressing as Lucy with a crown of candles and a white robe (normally to serve a breakfast of Lucy buns to the household) dates back to at least the nineteenth century. St Lucy herself, of course, is far older. According to her myths she was a young Christian girl living in Syracuse in the fourth century AD who turned down a suitor because she had promised her virginity to God and wished to give her dowry to

...more

My Finnish hosts have already told me a different story of Lucy – that her hated suitor claimed her eyes were the most beautiful in the world, so she gouged them out and sent them to him, pointing out that now he had her eyes he could leave her alone. The story is clearly a play on the legends of her losing her eyes in her martyrdom, but twisted into a delightfully nasty little fairy story. It’s telling, as well, that while most saints have a saint’s day, Lucy has her night.

This other Lucy is nothing like the demure, sweet victim of the hagiographies or the pure, white vision I’ve just seen outside the cathedral. Instead, on 13 December, she is said to ride through the skies with a cavalcade of the dead, of ghosts and, sometimes, of children who died while still unbaptised. Going house to house with her terrifying entourage, she looks for the food that has been left out for her. If all is well, she’ll eat the offerings and bring good fortune in return, and if she encounters any good children on her way she gives them treats. But if the food offerings are

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Christmas witch too – though an altogether kinder one – the Befana. An Italian variant, Befana, like Perchta, appears on Epiphany, and, like Perchta, she takes her name from the festival. She also gives good children sweets, but the bad children who meet Befana only have to contend with gifts of coal rather than being gutted. The history of these Christmas witches may well be one of the most complex of all the seasonal monsters. After all, only an utter mess of tangling beliefs can lead to a semi-benevolent, disembowelling witch who demands offerings, gives presents, and flies across the land

...more

magical woman who wasn’t directly Christian, whether or not the woman in question had anything to do with hunting or the moon (perhaps because Diana is the only pagan goddess whose name appears in the Bible). Herodias, meanwhile, is a figure who lived very much in grey areas, at least in medieval folklore. In the Bible she’s the wife of King Herod, but in stories told in the Middle Ages she was his daughter, who fell in love with John the Baptist. When her father found out, he ordered the saint beheaded. Herodias went to kiss the severed head, but John the Baptist (who had never returned her

...more

Washington Irving, in his book of Christmas traditions, Old Christmas, also remembered the telling of ghost stories – in his case, about a ghostly Crusading knight – at Christmas. Even Dickens, advocating so influentially for the more wholesome Christmas, did so through a ghost story in A Christmas Carol. Like the folklorists spinning beguiling fantasies of ancient pagan rituals, Jerome, Borlase, Dickens and the Jameses (M.R. and Henry) were tapping into the old need for darkness within the new, Victorian, family Christmas, when people were meant to be getting cosy round the tree or roasting

...more