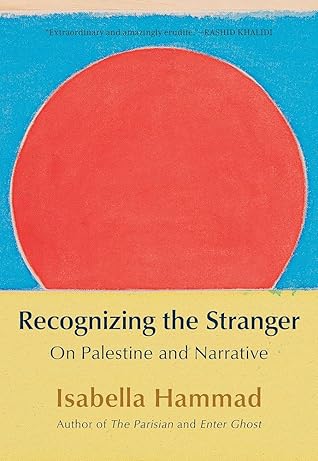

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 22 - September 22, 2025

The flow of history always exceeds the narrative frames we impose on it. Generations continue to be born, and we experience neither total apocalypse nor a happily-ever-after with any collective meaning beyond the endings of individual lives. Yet this narrative sense remains with us, flickering like a ghost through the revisions of postmodernism: we hope for resolution, or at least we hope that retrospectively what felt like a crisis will turn out to have been a turning point.

Individual moments of recognition are repeatedly overwhelmed by the energy of a political establishment that tells the onlooker: this is not what it looks like. It is too complicated to understand. Look away.

He kept asking me whether I thought we humans could ever act in the world purely as individuals, and not on behalf of groups. “For ourselves, alone,” he kept saying, “and not

for our groups.”

How many Palestinians, asked Omar Barghouti, need to die for one soldier to have their epiphany?

The Palestinian struggle has gone on so long now that it is easy to feel disillusioned with the scene of recognition as a site of radical change, or indeed as a turning point at all.

And yet the pressure is again on Palestinians to tell the human story that will educate and enlighten others and so allow for the conversion of the repentant Westerner, who might then descend onto the stage if not as a hero then perhaps as some kind of deus ex machina.

What I learned through writing this book is that literary anagnorisis feels most truthful when it is not redemptive: when it instead stages a troubling encounter with limitation or wrongness.

This is the most I think we can hope for from novels: not revelation, not the dawning of knowledge, but the exposure of its limit. To realize you have been wrong about something is, I believe, to experience the otherness of the world coming at you. It is to be thrown off-center. When this is done well in literature, the readerly experience is deeply pleasurable.

There’s often a moment, pivoting on the hinge of a repeated word or image, when things click into place, the lock turns, the trail of strange symbols suddenly reveal their meaningful interrelation, and the stage machinery rotates.

What in fiction is enjoyable and beautiful is often terrifying in real life. In real life, shifts in collective understanding are necessary for major changes to occur, but on the human, individual scale, they are humbling and existentially disturbing. Such shifts also do not usually come without a fight: not everyone can be unpersuaded of their worldview through argument and appeal, or through narrative.

“Having a strong reaction is not the same thing as having an understanding,” she writes, “and neither is the same thing as taking an action.”

It’s one thing to see shifts on an individual level, but quite another to see them on an institutional or governmental one. To induce a person’s change of heart is different from challenging the tremendous force of collective denial. And denial is arguably the opposite of recognition. But even denial is based on a kind of knowing. A willful turning from devastating knowledge, perhaps, out of fear.

Acknowledging the alterity in our minds and hearts is to reconcile ourselves to ambivalence, strangeness, and internal disunity.

Thus Said reverses the scene of recognition as I have described it. Rather than recognizing the stranger as familiar, and bringing a story to its close, Said asks us to recognize the familiar as stranger. He

gestures at a way to dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups. This might be easier said than done, but it’s provocative—it points out how many narratives of self, when applied to a nation-state, might one day harden into self-centered intolerance.

The present

onslaught leaves no space for mourning, since mourning requires an afterward, but only for repeated shock and the ebb and flow of grief. We who are not there, witnessing from afar, in what ways are we mutilating ourselves when we dissociate to cope? To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony. Let us remain there: it is the more honest place from which to speak.

The argument that Israel is exercising self-defense—already egregious when using military power against a population it occupies—in response to the Qassam Brigades operation of October 7 is untenable in the face of the wholesale slaughter, destruction of civilian infrastructure, and open discussion of mass transfer. Ten thousand dead children is not self-defense.

Most crucially and shamefully, the US vetoed the Security Council resolution demanding an immediate humanitarian ceasefire on December 8, 2023. The image of US representative Robert Wood alone raising his hand in dissent should leave a stain on Western consciousness. At the time, eighteen thousand Palestinians in Gaza had already been killed by Israeli bombardment. In the US Congress a war of discourse mistranslates Arabic words like “intifada” as “genocide”; elsewhere, an occupied population is attacked in what many Holocaust and genocide experts have called either “a textbook case of

...more

acquainted with the crime, having facilitated genocides in other countries such as Indonesia and Guatemala, for which they never faced retribution; indeed Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term “genocide,” considered the colonial replacement of Indigenous peoples by European colonists in the Americas to be a historical example of the crime.

While historians have classified massacres of Indigenous Americans and the Herero people as genocides, for example, no similar institutions or legal frameworks or systems of retribution have been constructed in their wake.

Meanwhile, the memory of the Holocaust is starting to function like the murder of another famous Jew, who was also a Palestinian, and who was called Jesus Christ, and in whose name all manner of catastrophes have been perpetrated over the centuries, exploitations and violent nationalisms, crusades and manifest destinies.

“Photography is unable to capture the flies,” he writes, “or the thick white smell of death. Nor can it tell about the little hops you have to make when walking from one corpse to the next.”

The rhetorical dehumanization of Palestinians since the beginning of the Zionist movement in the nineteenth century, entering the North

American mainstream in the sixties, has long nurtured Israeli—and Western—public consent for the Zionist project.

There is a temptation to leap forward rhetorically to reflect on the present: what will you have done? What that means is: there is still time. What that means is: time is running out. Every ten minutes, according to the WHO, a child is killed. It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing. That was a terrible moment, when the movements of the world were out of my hands.

In his essay on Shatila, Genet speaks extensively of the beauty of the Palestinians, who remind him of the beauty of the Algerians when they rose against the French. He describes it as “a laughing insolence goaded by past unhappiness, systems and men responsible for unhappiness and shame, above all a laughing insolence which realizes that, freed of shame, growth is easy.” The Palestinians in Gaza are beautiful. The way they care for each other in the face of death puts the rest of us to shame. Wael Dahdouh, the

Al Jazeera journalist who, when his family members were killed, kept on speaking to camera, stated recently with a calm and miraculous grace: “One day this war will stop, and those of us who remain will return and rebuild, and live again in these houses.”