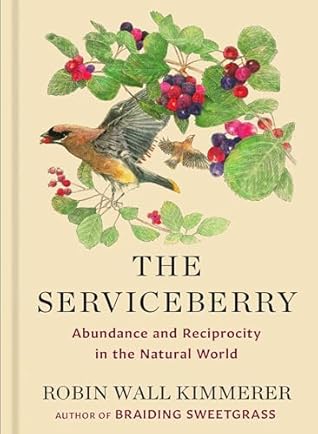

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 29 - November 29, 2025

To my good neighbors, Paulie and Ed Drexler.

Saskatoon, Juneberry, Shadbush, Shadblow, Sugarplum, Sarvis, Serviceberry—these are among the many names for Amelanchier. Ethnobotanists know that the more names a plant has, the greater its cultural importance. The tree is beloved for its fruits, for medicinal use, and for the early froth of flowers that whiten woodland edges at the first hint of spring. Serviceberry is known as a calendar plant, so faithful is it to seasonal weather patterns. Its bloom is a sign that the ground has thawed. In this folklore, this was the time that mountain roads became passable for circuit preachers, who

...more

Instead of changing the land to suit their convenience, they changed themselves. Eating with the seasons is a way of honoring abundance, by going to meet it when and where it arrives.

Serviceberries were a critical ingredient in the making of pemmican. The dried berries, along with dried venison or bison, were pounded to a fine powder, bound with rendered fat, and solidified into the original energy bars.

In the Anishinaabe worldview, it’s not just fruits that are understood as gifts, rather all of the sustenance that the land provides, from fish to firewood. Everything that makes our lives possible—the splints for baskets, roots for medicines, the trees whose bodies make our homes, and the pages of our books—is provided by the lives of more-than-human beings.

When we speak of these not as things or natural resources or commodities, but as gifts, our whole relationship to the natural world changes. In a traditional Anishinaabe economy, the land is the source of all goods and services, which are distributed in a kind of gift exchange: one life is given in support of another. The focus is on supporting the good of the people, not only an individual. Receiving a gift from the land is coupled to attached responsibilities of sharing, respect, reciprocity, and gratitude—of which you will be reminded.

Haudenosaunee neighbors, inherit what is known as “a culture of gratitude,” where lifeways are organized around recognition and responsibility for earthly gifts, both ceremonial and pragmatic. Our oldest teaching stories remind us that failure to show gratitude dishonors the gift and brings serious consequences. If you dishonor the Beavers by taking too many they will leave. If you waste the Corn, you’ll go hungry.

Recognizing “enoughness” is a radical act in an economy that is always urging us to consume more.

Ecopsychologists have shown that the practice of gratitude puts brakes on hyperconsumption. The relationships nurtured by gift thinking diminish our sense of scarcity and want. In that climate of sufficiency, our hunger for more abates and we take only what we need, in respect for the generosity of the giver. Climate catastrophe and biodiversity loss are the consequences of unrestrained taking by humans. Might cultivation of gratitude be part of the solution?

If our first response to the receipt of gifts is gratitude, then our second is reciprocity: to give a gift in return.

Gratitude and reciprocity are the currency of a gift economy, and they have the remarkable property of multiplying with every exchange, their energy concentrating as they pass from hand to hand, a truly renewable resource.

Materials move through ecosystems in a circular economy and are constantly transformed. Abundance is created by recycling, by reciprocity.

These processes are the models for principles of a circular economy, in which there is no such thing as waste, only starting materials. Abundance is fueled by constantly circulating materials, not wasting them.

If the Sun is the source of flow in the economy of nature, what is the “Sun” of a human gift economy, the source that constantly replenishes the flow of gifts? Maybe it is love.

In a gift economy, wealth is understood as having enough to share, and the practice for dealing with abundance is to give it away. In fact, status is determined not by how much one accumulates, but by how much one gives away. The currency in a gift economy is relationship, which is expressed as gratitude, as interdependence and the ongoing cycles of reciprocity. A gift economy nurtures the community bonds that enhance mutual well-being; the economic unit is “we” rather than “I,” as all flourishing is mutual.

The prosperity of the community grows from the flow of relationships, not the accumulation of goods.

Traditional potlatches are gift-giving celebrations, in which possessions are given away with lavish generosity to mark meaningful life events. The ceremonial feasts display the wealth of the givers, enhance their prestige, and affirm connections with a web of relations. The gifts received are likely to be given away at the next ceremony, keeping wealth in motion and cementing mutual bonds. This ritualized redistribution of wealth was banned by colonial governments, under the influence of missionaries in the 1800s.

These traditional values of relationship and reciprocity continue to resonate in contemporary Indigenous economics, as Dr. Ronald Trosper, a Salish-Kootenai economist has documented in his book Indigenous Economics: Sustaining Peoples and Their Lands. Making good relationships with the human and more-than-human world is the primary currency of well-being.

Five different tribes nurtured relationships with the federal government to forever protect an earthly gift to be held in common. This was a transformative step toward healing a long history of colonial taking. That hopeful model of Indigenous economics was abruptly curtailed when Donald Trump reversed the decision and instead conveyed rights to those sacred lands to a private uranium-mining company. It took an election to reverse it.

These two economic worldviews, of prosperity gained through individual accumulation and prosperity gained through sharing of the commons, underpin the history of colonization in this country.

This required a narrowing of the definition of well-being, from common wealth to individual wealth, from abundance to scarcity.

This Little Free Library movement has spread all over the country to share a love of reading and to bring books to everyone, in a gift economy. That is an incremental step beyond sharing a book with a friend to sharing with your neighborhood.

How does this sharing work in a larger community? Public libraries seem to me a powerful example of the way that gift economies can coexist with market economies, at a larger scale.

I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. Libraries are models of gift economies, providing free access not only to books but also music, tools, seeds, and more.

Oftentimes this avoidance is achieved by shifting one’s needs away from whatever is in short supply, as though evolution were suggesting “If there’s not enough of what you want, then want something else.” This specialization to avoid scarcity has led to a dazzling array of biodiversity, each species avoiding competition by being different.

Continued fealty to economies based on competition for manufactured scarcity, rather than cooperation around natural abundance, is now causing us to face the danger of producing real scarcity, evident in growing shortages of food and clean water, breathable air, and fertile soil. Climate change is a product of this extractive economy and is forcing us to confront the inevitable outcome of our consumptive lifestyle: genuine scarcity, for which the market has no remedy.

In fact, the “monster” in Potawatomi culture is Windigo, who suffers from the illness of taking too much and sharing too little. It is a cannibal, whose hunger is never sated, eating through the world. Windigo thinking jeopardizes the survival of the community by incentivizing individual accumulation far beyond the satisfaction of “enoughness.”

“It’s not really altruism,” she insists. “An investment in community always comes back to you in some way. Maybe people who come for Serviceberries will come back for Sunflowers and then for the Blueberries. Sure, it’s a gift, but it’s also good marketing.

plant communities are constantly in flux. From a bird’s-eye view, the “unbroken forest” is in fact a patchwork of stands of different ages and experience. Fires, landslides, floods, windstorms, outbreaks of insects, disease, and disasters of human origin disrupt the green blanket in unpredictable ways—and yet with a somewhat predictable response.

Their rampant growth captures nutrients and builds the more stable conditions in which their followers can flourish. Incrementally, they start to be replaced.

These communities have been called “mature” and sustainable, in contrast to the adolescent behavior of their predecessors. This transition from exploitation to reciprocity, from the individual good to the common good has been seen as a parallel to the transition that colonizing human societies must undergo, from hoarding to circulation, from independent to interdependent, from wounding to healing, if we are to thrive into the future.

I want to see emerging gift economies nurtured in the gaps carved out of the overbearing market economy. Both of these tools—incremental change and creative disruption—are available to us as agents of cultural transformation. I hope we will use them both. In these urgent times, we need to become the storm that topples the senescent, destructive economies so the new can emerge.

The gap edges, or ecotones, where two ecosystems, the new and the old, meet, are among the most diverse and productive of ecosystems, full of berries and birds.

Regenerative economies that reciprocate the gift are the only path forward. To replenish the possibility of mutual flourishing, for birds and berries and people, we need an economy that shares the gifts of the Earth, following the lead of our oldest teachers, the plants. They invite us all into the circle to give our human gifts in return for all we are given.