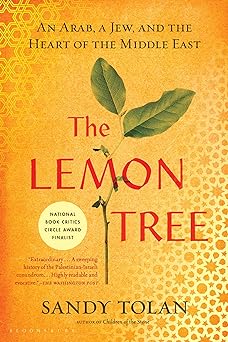

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Sandy Tolan

Read between

September 8 - September 14, 2025

"My choice is to stay here," she wrote. "I will not be able to look myself in the face if I leave when it gets difficult. I am going to stay present for the pain, and for the hope. I am an integral part of it all. I am part and parcel of this complexity. I am part of the problem because I came from Europe, because I lived in an Arab house. I am part of the solution, because I love."

One of the most recent victims was Iman al-Hams, an unarmed thirteen-year-old Palestinian girl. She was shot and killed by an Israeli officer, who then, according to accounts from his fellow soldiers, fired a stream of bullets into her body.

thirteen were babies who died at checkpoints as their mothers gave birth.

Numerous reports documented ambulances denied passage at checkpoints. Other

For many Israelis, the incident evoked memories of Jewish violinists forced to play for Nazi officers at concentration camps, and it created a national outrage. Many of the commentators believed the checkpoints were essential for protecting Israel from suicide bombers, but they believed the humiliation of the young Arab violinist, Wissam Tayem, had undercut Israel's moral authority and disgraced the memory of the Holocaust.

"They are building the wall," said Nidal, "so they don't have to look into our eyes."

"For Palestinians it didn't change the daily life. It went from bad to worse. I didn't go back to al-Ramla. We don't have our independent state, and we don't have our freedom. We are still refugees moving from one place to another place to another place to another place, and every day Israel is committing crimes. I can't even be on the board of the Open House. Because I'm Palestinian, not Israeli. If somebody comes yesterday from Ethiopia but he's Jewish, he will have all the rights, when I'm the one who has the history in al-Ramla. But for them I'm a stranger."

By not accepting the state of Israel or by not accepting the state of Palestine, I think none of us has a real life here. Israelis don't have a real life here, either. But if you're not okay, we're not okay. And if we're not okay, you're not okay."

Like an increasing number of Palestinians opposed to Oslo-type solutions, he believed that without return, the conflict will be eternal. "And it will be a tragedy for both people," he told Dalia.

"We share a common destiny here. I truly believe that we are so deeply and closely related—culturally, historically, religiously, psychologically. And it's so clear to me that you and your people are holding the key to our true freedom. And I think we could also say, Bashir, that we hold the key to your freedom. It's a deep interdependence. How can we free the heart, for our own healing? Is this possible?

For Dalia, the key to coexistence lay in what she called "the three A's": acknowledgment of what had happened to the Palestinians in 1948, apology for it, and amends.

But she believed this must be mutual—that Bashir must also see the Israeli Other—lest "one perpetuate the righteous victim syndrome and not take responsibility for one's own part in the fray."

How could you have a right, but not be able to exercise it?

wish more people were like you." I wish, Bashir had written Dalia sixteen years earlier, there had been a forest of Dalias.

"We couldn't find two people who could disagree more on how to visualize the viability of this land," Dalia said, standing and slipping on her sandals. "And yet we are so deeply connected. And what connects us? The same thing that separates us. This land."

"Our enemy," she said softly, "is the only partner we have."

"This dedication is without obliterating the memories. Something is growing out of the old history. Out of the pain, something new is growing.

There was a pause. “I am aware of your history in Europe,” Bashir said. “So you recognize the Holocaust?” Solli asked. “Yes. But,” Bashir added, “you have gone from the victims to the victimizers.”

When he returned Bashir learned that, each night since the soldiers took him, his daughter had awakened to her own screams.

Every week, they go the site of a different village that once stood in old Palestine. They want to try to reclaim, at least for moments, a sense of their broader homeland, and to show, in the words of their guide, that “what we can do is to be here. This land is not just belonging to Israelis.”

They are unable to travel to Jerusalem to pray at ancient holy sites, since it is now part of a “unified” Israeli capital and off-limits to most Palestinians.

Since Dalia and Bashir last saw each other, in 2005, multiple wars have devastated Gaza, killing more than 3,200 Palestinian civilians, including more than one thousand children, mostly killed by Israeli air strikes. During that same time, twenty-nine Israeli civilians died from Hamas or other militant rocket attacks launched from Gaza. None of those were children. Yet, despite the dramatic disparity in casualties, throughout Israel, and in the media, Palestinians are often portrayed as the aggressors, and Israelis, the victims.