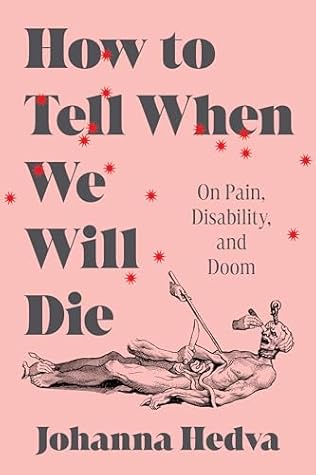

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 10 - January 26, 2025

In order to live, we tell ourselves stories that do not include illness.

Suffering is purposeful, glorious, noble, deserved, punitive—

If we give up because of an illness, injury, or disability, we keep it secret, ashamed. If we cannot do something because our bodies won’t let us, like walk to the mailbox or pick up a grocery bag—if we simply are not able to—we hang our heads humiliated.

When it dawns on some of us that we will always need, that we have no choice but to be permanently marked by our insolvency, the first response is to hate ourselves.

In the stories we tell ourselves, a sick or disabled person’s condition does not expand and traverse its voltaic, crackling, multivalent world, but collapses under its own limit.

What happens when the stories we tell ourselves in order to live are forced to include illness and disability

How do we write stories that use these words in ways that unfurl, rather than foreclose, their nuance?

To be alive on this earth is to live in the abundance of the body’s peculiarities,

I want to reckon with the twinned facts that our bodies are fragile and in need of constant care and support, but that we have built our world as if the opposite were true.

What exactly is supported, even strengthened, under the regime of the singular story that tells illness as the temporary aberration to a fantastical norm of wellness;

I like to truncate this definition, to make the body, especially the human kind, simply a thing that needs. Because what else would support be—but needed?

It was an education in how time and debt are entangled, with how disability troubles capitalism’s unholy marriage of time and money,

I also knew that, no matter where it came from, the hurt was real, it sounded like my own voice, and it lived in me now. It was a story being told about me that I started to tell about myself.

In crip community, interdependence, support, and mutual aid are held closer than anything else,

We are not alive because of our stories, but it is true to say that, in telling them, they birth and rebirth us, and who doesn’t need to be reborn from time to time?

It’s not that it pulled me out of the hole I was in, but it made the hole something other than only a hole.

I don’t want or need writers or artists to be good, pure, ethically uncompromised.

If they cannot give me the why of these lacunae, I at least want the how. “How did you arrive at that thought?” I kept asking.

You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism.

But our work has not yet gotten into the world’s water supply.

The public understanding of terms like “disability” is still the medical model, that it is a body impaired and malfunctioning that requires course-correction.

I return to the same question over and over: What does ableism give us that we can’t let go of? Why do we keep it so close, stick to its well-worn ruts?

Disability describes a condition that is both more othered from and profoundly closer to one’s body than any other political condition that I can think of.

disability will arrive for everyone, sooner or later.

It is always there, and the question is not if but when it will arrive for you. This is not the same as any other political identity. Not everyone on this planet will one day become queer or not white or a woman or colonized, but they will become disabled.

No matter what form of disability arrives for you, it will bring struggle, suffering, incapacity, limit, and pain.

Sometimes your daily to-do list must include things like “cook” and “shower,” and sometimes you won’t be able to check them off as done.

Ableism protects us from the most brutal truth: that our bodies will disobey us, malfunction, deteriorate, need help, be too expensive, decline until they finally stop moving, and die.

How, then, to ask people to execrate ableism as an ideology of harm, discrimination, and oppression when it is the very thing that insulates us from the fact of our own impending limits and mortality?

“Death is fast, and doom is slow.”

I held one’s hand as she died, and although I’d let go of the other’s hand long before, we still held on to each other in many ways.

I want to say something about the ableism behind the idea that disability is “a fate worse than death.” But, since disability and illness are the most universal facts of life, aren’t they the only fates?

With this event, I became marked by the knowledge that death won’t be romantic, it won’t be grand, it’s a small thing that’s always close by, very close, in fact, at any given moment you can reach out and hold it, if you want to you can, without even reaching very far, go ahead, it’s right there, so close, what’s stopping you?, exactly what, if anything, is stopping you?

What about those of us whose lives are described not as lives at all, but as fates worse than death?

It’s been suggested by people who knew her that Joan Didion wrote to find out what she thought.

The future does not exist. Not yet. We cannot tell it, which is to say we cannot know it. And yet we must live as if we can.

It’s not what I thought but what I have found thinking can do, all the contradictions, lucubrations, ways in which my mind changed.

It doesn’t return home because home was never a place of shelter. Who built that house?

There are as many kinds of light as there are darknesses.

How many of us have already met our doom and then had to get out of bed and go on?

How privileged are you if you first require hope in order to act? What about those where hope was a luxury they couldn’t afford, and still they wrote books, they made music, they sang? They keep singing.

my wish in finally putting the writing into the world is not to claim it as mine but to offer it as companion to whomever might need it.

the body is the page upon which we write our lives.

Solidarity is a slippery thing. It’s hard to feel in isolation.

If being present in public is what is required to be political, then whole swathes of the population can be deemed apolitical simply because they are not physically able to get their bodies into the street.

Public space is never free from infrastructures of power, control, and surveillance; in fact, it is built by them.

As Butler says, there is always one thing true about a public demonstration: the police are already there, or they are coming.

we must contend with the fact that many whom these protests are for are not able to participate in them, which means they are not able to be visible as political subjects.

the central question of Sick Woman Theory has been formed and honed: How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?

So, a chronic illness is an illness that lasts a lifetime. In other words, it does not get better. There is no cure.