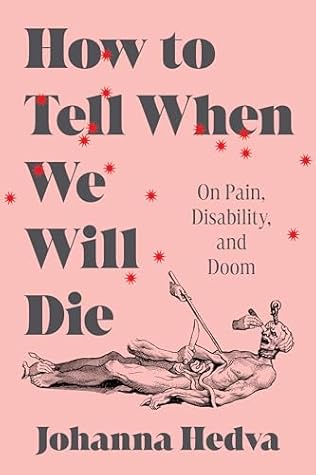

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 2 - January 4, 2025

In order to live, we tell ourselves stories that do not include illness. Our heroes die on the battlefield, not from chronic pain. Diarrhea never makes its way into myth. Tragedies are devoid of menstrual cramps. Irritable bowel syndrome is, oddly, absent from the suspense genre. Suffering is purposeful, glorious, noble, deserved, punitive—Ajax falls on his sword, Juliet drinks the poison, Jane Eyre is undone by fire, Prometheus pays for his transgression with his liver. It is not caused by the terrestrial inconveniences of co-pays, misdiagnoses, long lines at the pharmacy, the vanishing of

...more

We count among our strengths our strength, and among our weaknesses, our weakness, and the only radicality we can yield to this binary is to invert it, to count what is usually considered weak as maybe some other kind of strength.

The definition of “the body” that I like the most is that it’s anything that needs support.

Becoming disabled, for me, was an education in many things, but sometimes I think it was elementally about relearning how to understand dependency, and how disability makes it impossible to ignore that we are ontologically dependent, knotted into each other and everything. It was an education in how time and debt are entangled, with how disability troubles capitalism’s unholy marriage of time and money, putting a person again and again into the condition of financial and bodily insolvency, where there is never enough time and nothing can be paid back.

Once, while at a crip friend’s house on the night they had a dinner party, I couldn’t leave the bed on the second floor because I was in a flare. The crips who could climbed the stairs and got into bed with me, and we FaceTimed the crips who are wheelchair users who were on the first floor. That was the best dinner party I’ve ever been to, and I never made it to the table.

We are not alive because of our stories, but it is true to say that, in telling them, they birth and rebirth us, and who doesn’t need to be reborn from time to time?

I don’t want or need writers or artists to be good, pure, ethically uncompromised. They can have gaps and holes and leaps; I do not need their apologies, penance, or punishment. What I do want is writers and artists unafraid to be honest in accounting for when their beliefs take them to somewhere they didn’t deliberately aim for, when their actions are determined by ideological beliefs they have absorbed uncritically and now express without notice. If they cannot give me the why of these lacunae, I at least want the how. “How did you arrive at that thought?” I kept asking.

You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism. If you remember one thing from that definition, I’d like it to be the last sentence.

Disability describes a condition that is both more othered from and profoundly closer to one’s body than any other political condition that I can think of. It is a radical encounter with the needs of that body and therefore the ways in which that body’s autonomy is limited and its dependency decided—and this dependency, this ontology of need, is what yokes it into a matrix of power: how it has, or does not have, power, and what sort of material conditions that determines.

Does this body have the power to guarantee its own survival, support, resources, thriving? With disability, the answer to these questions is often no. This is what makes disability political—because the political is foremost about power: who has power, who does not, why, and what can be done about it.

I am in agreement with those in the disabled community who would portend that, no matter how it arrives, disability will arrive for everyone, sooner or later.

Ableism protects us from the most brutal truth: that our bodies will disobey us, malfunction, deteriorate, need help, be too expensive, decline until they finally stop moving, and die. Ableism is what lets us believe that this doesn’t have to be true, or at least, that we can forestall it, keep it at bay, and that this is based entirely upon our own will. Ableism and its fantasies allow us to operate as if our abilities, our bodies, are always at our command, under our control, and that they will function when and how and for as long as we want them to, as we need them to. Of course, we’d

...more

How do we build a politic that stares into the face of our own end and finds a way to continue? It’s an unendurable task. The only way I can think to do this is to say, “Let’s do it together.”

It has occurred to me that maybe I’ve become so ferocious in my disability activism because it retroactively rescues my mother.

The shaman only got a few seconds into the ceremony before she stopped and said, “Whoa. Is this her personality? She’s like a tank!” We laughed. “Yes,” I said. “That’s her.”

If a person attempted to curtail her independence, murdering them was the first option she reached for. Who do you think you are?

Death is fast. Doom is slow.

I want to say something about the ableism behind the idea that disability is “a fate worse than death.” But, since disability and illness are the most universal facts of life, aren’t they the only fates?

I became marked by the knowledge that death won’t be romantic, it won’t be grand, it’s a small thing that’s always close by, very close, in fact, at any given moment you can reach out and hold it, if you want to you can, without even reaching very far, go ahead, it’s right there, so close, what’s stopping you?, exactly what, if anything, is stopping you?

rather than writing to express yourself, writing is the act of finding something out about yourself that you didn’t already know.

I write to find out what is possible to think, meaning it’s the changing of the thought that I chase, that miraculous capacity that can expand. Once I have a phrase, a sentence, a paragraph down on the page, what thrills me is to watch what happens to the thought if it’s written in questions versus statements, this word rather than that word, a different syntax, vocabulary, punctuation. I want to know what thinking can do—what it makes, destroys, negotiates, protects, transgresses against; how it can be knife, fist, kiss, well, map, key.

For many years I was uneasy about this book going into the world as mine because the normative aesthetics of care and illness are just not my vibe. I’m a goth kink queen, a faggy big-cock power-top who plays doom metal—it’s a different sort of mood board. Care is so domesticated, maternalized, tied up with notions of nurturing and selflessness. But to be disabled and require care is to deal constantly with the nastiest of body horrors: diarrhea as if from a broken spigot, skin slit into slices, so much pus, unstoppable bleeding, clots of it like black ash, not to mention the sublime-like

...more

I bring doom into the conversation to show that it is a place to begin, not to end.

How privileged are you if you first require hope in order to act? What about those where hope was a luxury they couldn’t afford, and still they wrote books, they made music, they sang? They keep singing.

My editor asks: “Why does it need to be painful?” My partner asks: “Why do you fight so much?” My audience asks: “But where is hope in the darkness of your work?” My ancestors ask: “Why do you make your hands claw around the lie of your solitude?” My government asks: “Why won’t you let us use your body to feed the worms?” I ask: “What can I write down?”

And to those who would say they don’t “believe in” astrology, I would reply, Do you not believe in all the languages you don’t know how to speak? Do you not believe in calculus, Guaraní, C++?

Solidarity is a slippery thing. It’s hard to feel in isolation. In bed, in pain, I started to think about the kind of solidarity in which I could participate as someone stuck at home, alone. I started to think about what modes of protest are afforded to sick and disabled people at all.

If we take Hannah Arendt’s definition of the political—which is still one of the most dominant in mainstream discourse—as being any action that is performed in public, we must contend with the implications of what, of whom, that excludes. If being present in public is what is required to be political, then whole swathes of the population can be deemed apolitical simply because they are not physically able to get their bodies into the street.

There are two failures here though. The first is her reliance on a “public”—which requires a private, a binary between visible and invisible space. This means that whatever takes place in private is not political.

“The personal is political,” can also be read as saying, “The private is political.” Because, of course, everything you do in private is political:

Arendt failed to account for who is allowed into public space, which means she failed to account for who’s in charge of public space. Public space is never free from infrastructures of power, control, and surveillance; in fact, it is built by them.

When you have chronic illness, life is reduced to a relentless rationing of energy.

For those without chronic illness, you can spend and spend without consequence: the cost is not a problem. For those of us with limited funds, we have to ration, we have a limited supply, we often run out before lunch.

Ann Cvetkovich writes: “What if depression, in the Americas, at least, could be traced to histories of colonialism, genocide, slavery, legal exclusion, and everyday segregation and isolation that haunt all of our lives, rather than to be biochemical imbalances?” I’d like to change the word “depression” here to all mental illnesses. Cvetkovich continues: “Most medical literature tends to presume a white and middle-class subject for whom feeling bad is frequently a mystery because it doesn’t fit a life in which privilege and comfort make things seem fine on the surface.” In other words,

...more

For those living outside of America, the reach of this American imperialist ideology becomes a horizon of doom. Dr. Samah Jabr, the head of the Mental Health Unit within the Palestinian Ministry of Health, has noted that PTSD altogether is a Western concept: “PTSD better describes the experiences of an American soldier who goes to Iraq to bomb and goes back to the safety of the United States. He’s having nightmares and fears related to the battlefield and his fears are imaginary. Whereas for a Palestinian in Gaza whose home was bombarded, the threat of having another bombardment is a very real

...more

Whiteness is what allows for such oblivious neutrality; it is the premise of blankness, the presumption of the universal.

I have found that I prefer to let the category of disability be unruly, overflowing, crawling with variety rather than the opposite, forcing it to follow rules, building hard limits, insisting on its immutability. What body or mind would fit in such a carceral space?

As I said, I need them to define and categorize me—submitting to them affords me meds and therapies at the same time that it yokes me to the medical- industrial complex—and this is the conundrum all sick and disabled people live with. To be pathologized is to be allowed to survive.

One of the aims of Sick Woman Theory is to resist the notion that one needs to be legitimated by an institution, so that they can try to fix you according to their terms. You don’t need to be fixed, my queens—it’s the world that needs the fixing.

And, crucially, the Sick Woman is whom capitalism needs to perpetuate itself. Why? Because to stay alive, capitalism cannot be responsible for our care—its logic of exploitation requires that some of us die. For capitalism to support care would be the end of capitalism.

“Sickness” as we speak of it today is a capitalist construct, as is its perceived binary opposite, “wellness.” Under capitalism, the “well” person is the person well enough to go to work. The “sick” person is the one who is not well enough to work.

Here’s an exercise: Go to the mirror, look yourself in the face, and say out loud, “To take care of you is not normal. I can only do it temporarily.” Saying this to yourself will merely be an echo of what the world repeats all the time. What would happen if we decided to say the opposite?

“The blast radius of disability” is a phrase that will make demolishing, bone-deep sense if you’re in it already. Unless born with a disability, you are like many to whom it happens because of an injury, illness, or diagnosis. In these cases, there is a clear before and after, your life sliced into two parts—what you used to be like, and what you are now—and disability functions narratively in this story as the dramatic pivot. There is before the blast. There is after. And now there is you in that devouring cloud that won’t stop eating everything.

Maybe the blast radius of disability destroys everything and also makes new worlds. Maybe these are worlds of paradox: both a radical limitation of what you used to be able to do and an explosion of the horizon around what you thought would ever be possible.

The thing about illness and uprisings is that they both show up as surprises when they’re not. Illness, debility, disability, a pronounced dependency, are the most inevitable, the least surprising, the most commonly held experiences for every living being. Why do they appear so untimely? In one way, the answer is obvious: it’s just ableism that makes us turn away from this thing we share. But it’s also interesting to think about the form of this surprise, what it is to be jolted by what was there, is always there, all along.

Disability, however, operates according to “crip time,” a foundational term in the language of disability justice. Alison Kafer describes crip time as the kind of time that “requires reimagining our notions of what can and should happen in time, or recognizing how expectations of ‘how long things take’ are based on very particular minds and bodies.… Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds.”

In illness, time slows down so extremely as to become still and unbearably heavy. For the sick person, or someone caring for the sick, time freezes, hardening around the body, locking everything into this new center of gravity, bracing in the blast radius. All that can be done is to wait. The future gets further and further away, and the present moment—the one soaked in illness—becomes huge and cruel. In illness, the now feels like punishment.

I like thinking that activism will always fail, because it means that the decision to take action, to act as though what we do matters, even in the face of certain defeat, is its own purpose. It’s not going to get you paid or bring you victory or prepare you for some next success. It’s not going to demonstrate your purity, your moral superiority. It’s not about what you say, dream, or hope for. It’s about what we can do, right here, right now, for each other. It’s about starting where you are, not where you wish you were. It is important because what we do and how we do it is important. It’s

...more

Oppression, domination, and violence live first and foremost in our bodies. As much as they are ideological systems, their effect is always material; they deal in matter—flesh, bones, blood.

insanity is simply a measure of how one has become untethered to reality and its laws.