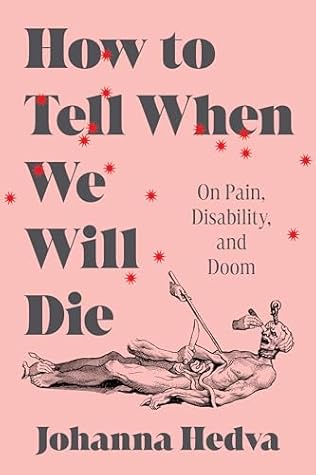

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 16 - December 13, 2024

I want to say something about the ableism behind the idea that disability is “a fate worse than death.” But, since disability and illness are the most universal facts of life, aren’t they the only fates?

the body is the page upon which we write our lives.

How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?

Whereas for a Palestinian in Gaza whose home was bombarded, the threat of having another bombardment is a very real one. It’s not imaginary … There is no ‘post’ because the trauma is repetitive and ongoing and continuous.

The most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself.

Perhaps you learn that in the disabled community, some of us like to add “temporarily” to the category of the “abled,” for they are simply those for whom the blast has not happened yet.

The thing about illness and uprisings is that they both show up as surprises when they’re not. Illness, debility, disability, a pronounced dependency, are the most inevitable, the least surprising, the most commonly held experiences for every living being. Why do they appear so untimely? In one way, the answer is obvious: it’s just ableism that makes us turn away from this thing we share. But it’s also interesting to think about the form of this surprise, what it is to be jolted by what was there, is always there, all along.

Capitalism objectifies the body. It views the body as an exploitable resource and attempts to render it indestructible and unstoppable with the aid of technology.… And yet as advanced capitalism has deemed the physical body an obsolete, outdated tool, the body still remains. It continues to fail under capitalist conditions and gets pathologized as illness. The body is another inconvenience that must be enhanced and optimized.

Over the years, I’ve noticed how often I have wanted the universal to consolidate my individuality, when what makes more sense is to simply be okay without it.

What we watched happen with COVID-19—and are still watching—is what happens when care insists on itself, when the care of others becomes mandatory, when it takes up space and money and labor and energy.

The world isn’t built to give care freely and abundantly.

Revolutionary care will take all of us—it will take all of us operating on the principle that if only some of us are well, none of us are—which demands that we live, not for the myth of the individual’s autonomy, but as though we are all interconnected.

For some of us, there is a relationship between healing and justice because what oppresses us has also made us suffer trauma and its accompanying symptoms. Oppression, domination, and violence live first and foremost in our bodies.

The definition of masculinity is its capacity to be free of the labor of perception at all—it perceives, yes, but only one way.

My problem is not only that I long for a cock of my own—my problem is that my ultimate dream is to make a cis man want to disown and remove his cock by his own hand. This has proven hard to accomplish, but a “girl” can dream, can’t “she”?

Kink, to me, is about the deviations that arise around power and pleasure; kink is anything that ruptures the seemingly impervious actions, rules, and choreographies that stabilize power—and the pleasure that comes from this rupture. It doesn’t have to only be about sexual power and pleasure, but the sexual is often the site where both power and pleasure feel the most potently echoic of each other. (Sometimes I think heterosexuality is the kinkiest thing there is because it’s always about how the most normie power represses pleasure, and the pleasure is in the repression itself. Ugh!)

What I love about kink is that it starts from the premise that we’re all freaks and then asks how to support that. Care starts from the opposite place, framing illness, disability, and debility as freak moments out of the ordinary that must be managed back into normalcy. Where kink foregrounds desire, choice, agency, and consent, care is incarcerated in duty, obligation, and burden, so no wonder care feels like a drag and kink is way more fun. At the heart of both kink and care is the darkly throbbing fact of power: in order for kink to work, power has to not only be acknowledged but engaged

...more

In the disabled community, we prefer the word “capacity” to “capability.” Yes, you might be capable of doing something, but do you have the capacity for it in this moment?

heteropessimism, which is the recent trend-theory where straight women feel bad about themselves for liking men, the humiliation and abjection of being attracted to that which oppresses you.

Why is a man losing his mind and caterwauling with need so much more sympathetic than a woman losing hers? Is it that a man’s self-destruction is something we feel moved to prevent, while a woman’s feels inevitable, so why bother to try to stop it?

Is ambition that’s propelled by a need to survive somehow not ambition? Or is it—under capitalism—the only kind?

Icarus flew too close to the sun because he was trying to flee the conditions he was born into.

If access is seen as one individual’s “special needs” or “accommodations,” that access can then be separated from the structural inaccessibility of the world that necessitates it. It scales disability down to the quirk of a single person’s body, an extravagance to be indulged, an inconvenience to be controlled.

We’ve framed care within the context of debt—where my “giving” care to you means I’m depleting my own stash, and your “taking” from me means that now you owe me—and although we’ve made debt into an index of our deficiency, we’ve also made it the only possible condition of life under capitalism. To be alive in capitalism is by definition to live in debt, and yet we’ve defined debt not as a kind of radical interdependency, as the ontological mutuality of being alive together on this planet—which it is—but as all that reveals our worst, what happens when we fail, a moral flaw that ought to be

...more

If the future is anything, it’s disabled—and that is true for everyone.