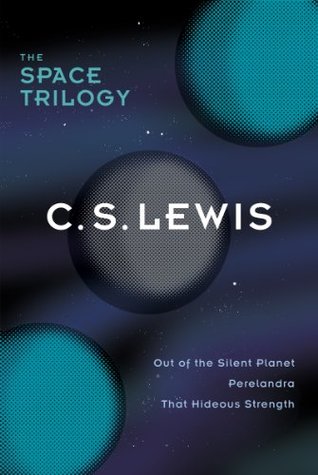

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Stretched naked on his bed, a second Dana, he found it night by night more difficult to disbelieve in old astrology: almost he felt, wholly he imagined, “sweet influence” pouring or even stabbing into his surrendered body.

But Ransom, as time wore on, became aware of another and more spiritual cause for his progressive lightening and exultation of heart. A nightmare, long engendered in the modern mind by the mythology that follows in the wake of science, was falling off him. He had read of “Space”: at the back of his thinking for years had lurked the dismal fancy of the black, cold vacuity, the utter deadness, which was supposed to separate the worlds. He had not known how much it affected him till now—now that the very name “Space” seemed a blasphemous libel for this empyrean ocean of radiance in which they

...more

And yet, he thought, beyond the solar system the brightness ends. Is that the real void, the real death? Unless . . . he groped for the idea . . . unless visible light is also a hole or gap, a mere diminution of something else. Something that is to bright unchanging heaven as heaven is to the dark, heavy earths. . . .

He noticed, too, that even the smallest hummocks of earth were of an unearthly shape—too narrow, too pointed at the top and too small at the base. He remembered that the waves on the blue lakes had displayed a similar oddity. And glancing up at the purple leaves he saw the same theme of perpendicularity—the same rush to the sky—repeated there.

The delusions recurred every few minutes as long as this stage of his journey lasted. He learned to stand still mentally, as it were, and let them roll over his mind. It was no good bothering about them. When they were gone you could resume sanity again.

Ransom found this difficult. At last he said: “Is the begetting of young not a pleasure among the hrossa?” “A very great one, Hmn. This is what we call love.” “If a thing is a pleasure, a hmn wants it again. He might want the pleasure more often than the number of young that could be fed.” It took Hyoi a long time to get the point. “You mean,” he said slowly, “that he might do it not only in one or two years of his life but again?” “Yes.” “But why? Would he want his dinner all day or want to sleep after he had slept? I do not understand.” “But a dinner comes every day. This love, you say,

...more

only see slower things lit by it, so that for us light is on the edge—the

“The hrossa used to have many books of poetry,” they added. “But now they have fewer. They say that the writing of books destroys poetry.”

We think that Maleldil would not give it up utterly to the Bent One, and there are stories among us that He has taken strange counsel and dared terrible things, wrestling with the Bent One in Thulcandra. But of this we know less than you; it is a thing we desire to look into.”

And I realized that I was afraid of two things—afraid that sooner or later I myself might meet an eldil, and afraid that I might get “drawn in.” I suppose everyone knows this fear of getting “drawn in” the moment at which a man realizes that what had seemed mere speculations are on the point of landing him in the Communist Party or the Christian Church—the sense that a door has just slammed and left him on the inside.

The very names of green and gold, which he used perforce in describing the scene, are too harsh for the tenderness, the muted iridescence, of that warm, maternal, delicately gorgeous world. It was mild to look upon as evening, warm like summer noon, gentle and winning like early dawn. It was altogether pleasurable. He sighed.

As he let the empty gourd fall from his hand and was about to pluck a second one, it came into his head that he was now neither hungry nor thirsty. And yet to repeat a pleasure so intense and almost so spiritual seemed an obvious thing to do. His reason, or what we commonly take to be reason in our own world, was all in favor of tasting this miracle again; the childlike innocence of fruit, the labors he had undergone, the uncertainty of the future, all seemed to commend the action. Yet something seemed opposed to this “reason.” It is difficult to suppose that this opposition came from desire,

...more

As he stood pondering over this and wondering how often in his life on Earth he had reiterated pleasures not through desire, but in the teeth of desire and in obedience to a spurious rationalism, he

Were all the things which appeared as mythology on Earth scattered through other worlds as realities?

This itch to have things over again, as if life were a film that could be unrolled twice or even made to work backward . . . was it possibly the root of all evil? No: of course the love of money was called that. But money itself—perhaps one valued it chiefly as a defense against chance, a security for being able to have things over again, a means of arresting the unrolling of the film.

“Maleldil is telling me,” answered the woman. And as she spoke the landscape had become different, though with a difference none of the senses would identify. The light was dim, the air gentle, and all Ransom’s body was bathed in bliss, but the garden world where he stood seemed to be packed quite full, and as if an unendurable pressure had been laid upon his shoulders, his legs failed him and he half sank, half fell, into a sitting position.

Sex is, in fact, merely the adaptation to organic life of a fundamental polarity which divides all created beings.

There was a quality in the very muscles of