Kindle Notes & Highlights

Leonardo da

Vinci used atmospheric perspective to great effect in works such as

Madonna of the Rocks (fig. 17-2) and Mona Lisa

Ghiberti retained the medieval narrative method of presenting several episodes within a single frame.

In Isaac and His Sons, the women in the left foreground attend the

birth of Esau and Jacob in the left background. In the central foreground, Isaac sends Esau and his dogs to hunt game. In the right

foreground, Isaac blesses the kneeling Jacob as Rebecca looks

Another

was the revival of the freestanding nude statue. The first Renaissance sculptor to portray the nude male figure in statuary was Donatello.

Donatello, David, ca. 1440–1460. Bronze, 5′ 2

1

–4″high.

Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Donatello’s David possesses both the relaxed contrapposto and the

sensuous beauty of nude Greek gods (fig. 5-63). The revival of classical

statuary style appealed to the sculptor’s patrons, the Medici.

Verrocchio directed a flourishing bottega (studio-shop) in Florence that attracted many students,

among them Leonardo da Vinci.

how clearly

he knew the psychology of brash young men.

Andrea del Verrocchio, David, ca. 1465–1470. Bronze,

4′ 1

1

–2″high. Museo Nazionale...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Verrocchio’s David, also made for the Medici, displays a brash confidence.

The statue’s narrative realism contrasts strongly with the quiet ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Hercules and Antaeus,

ca. 1470–1475. Bronze, 1′ 6″high with base. Museo Nazion...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Bernardo Rossellino, tomb of Leonardo Bruni, Santa

Croce, Florence, Italy, ca. 1444–1450. Marble, 23′ 3

1

–2″high.

Rossellino’s tomb in honor of the humanist scholar and Florentine

chancellor Leonardo Bruni combines ancient Roman and Christian

motifs. It established the pattern for Renaissance wall tombs.

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi, altarpiece from the Strozzi chapel, Santa Trinità, Florence,

Italy, 1423. Tempera on wood, 9′11″× 9′ 3″. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Gentile was the leading Florentine painter working in the International style. He successfully blended naturalistic details with

Late Gothic splendor in color, costume, and framing ornamentation.

Masaccio, Tribute Money, Brancacci chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence,

Masaccio’s figures recall Giotto’s in their simple grandeur, but they convey a greater psychological and physical credibility. He modeled his figures

with light coming from a source outside the picture.

Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, Brancacci

chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, Italy, ca. 1424–1427.

Masaccio, Holy Trinity, Santa Maria Novella, Florence,

Italy, ca. 1424–1427. Fresco, 21′10

5

–8″× 10′ 4

3

Masaccio’s pioneering Holy Trinity is the premier early-15th-century

example of the application of mathematics to the depiction of space

according ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

for many Quattrocento Italian artists, humanist concerns were not

a primary consideration.

The Dominicans (see “Mendicant Orders,” Chapter 14, page 404) of San Marco had dedicated themselves to lives

of prayer and work, and the religious compound was mostly spare

and austere to encourage the monks to immerse themselves in their

devotional lives.

Fra Angelico, Annunciation, San Marco, Florence, Italy, ca. 14...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The two figures appear in a

plain loggia resemblin...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Like most of Fra Angelico’s

paintings, Annunciation, with its simplicity and directness, still

has an almost universal appeal and fully reflects ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

An orphan, Fra Filippo spent his youth in a monastery adjacent to the church of Santa Maria del Carmine, and when

he was still in his teens, he must have met Masaccio there and witnessed the decoration of the Brancacci chapel.

The Carmelite brother interpreted his subject in a surprisingly worldly manner.

is a beautiful young mother, albeit with a transparent halo, in an elegantly furnished Florentine home, and neither she nor the Christ

Child, whom two angels hold up, has a solemn expression.

Significantly, all figures

reflect the use of live models

this work shows how

far artists had carried the humanization of th...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

sensuous beauty of this world.

Piero della...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

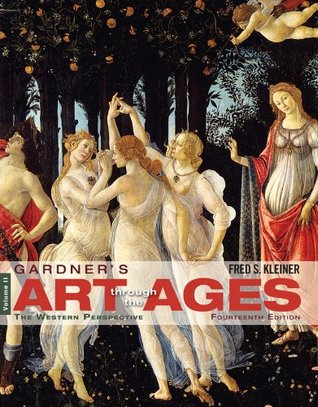

Botticelli, Birth of

Venus, ca. 1484–1486.

Tempera on canvas,

5′ 9″× 9′ 2″. Galleria

degli Uffizi, Florence.

The theme was the subject of

a poem by Angelo Poliziano (1454–1494), a leading humanist of

the day.

In this painting,

unlike in Primavera, Botticelli depicted Venus as nude. As noted

earlier, the nude, especially the female nude, was exceedingly rare

during the Middle Ages.

Marsilio

Ficino (1433–1499), for example, made the case in his treatise On

Love (1469) that those who embrace the contemplative life of reason—including, of course, the humanists in the Medici circle—will

immediately contemplate spiri...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Indeed, Botticelli’s

elegant and beautiful linear style (he was a pupil of Fra Filippo

Lippi, fig. 16-24) seems removed from all the scientific knowledge

15th-century artists had ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

osPedale degli innocenti

At the end of the second decade of the 15th

century, Brunelleschi received two important

architectural commissions in Florence—to

construct a dome (fig. 16-30a) for the city’s

late medieval cathedral (fig. 14-18), and to

design the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Hospital of the Innocents, fig. 16-31), a home for

Florentine orphans and foundlings.

Most scholars regard Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti

as the first building to embody the new Renaissance architectural

style.

Both plan and elevation conform to a module that embodies

the rationality of ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Santo Spirito fully

expresses the new Renaissance spirit that placed its faith in reason

rather than in the emotions.

In this modular

scheme, as in the loggia of the Ospedale degli Innocenti (fig. 16-31),

a mathematical unit served to determine the dimensions of every

aspect of the church.

This

facade also introduced a feature of great historical consequence—

the scrolls that simultaneously unite the broad lower and narrow

upper levels and screen the sloping roofs over the aisles. With variations, similar spirals appeared in literally hundreds of church facades throughout the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

The height of Santa Maria

Novella (to the pediment tip) equals its width. Consequently, the

entire facade can be inscribed in a square.

They believed in the

eternal and universal validity of numerical ratios as the source of

beauty. In this respect, Alberti and Brunelleschi revived the true

spirit of the High Classical age of ancient Greece, as epitomized by

the architect Iktinos and the sculptor Polykleitos,

Leon Battista Alberti, west facade of

Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy, 1456–1470.

Alberti’s design for the facade of this Gothic church

features a pediment-capped temple front and pilasterframed arcades. Numerical ratios are the basis of the

proportions of all parts of the facade.

In the 16th and 17th

centuries, the popes became the major patrons of art and architecture in Italy

but a new style, called Mannerism,

challenged Renaissance naturalism almost as soon as Raphael had

been laid to rest

Indeed, the modern notion of the “fine arts” and the exaltation of

the artist-genius originated in Renaissance Italy.

Among the

many projects the ambitious new pope sponsored were a design

for a modern Saint Peter’s (figs. 17-22 and 17-23) to replace the

timber-roofed fourth-century basilica

Raphael adopted Leonardo’s

pyramidal composition and modeling of faces

and figures in subtle chiaroscuro.

Although Raphael experimented with

Leonardo’s dusky modeling, he tended to return to Perugino’s lighter tonalities and blue

skies. Raphael preferred clarity to obscurity, not fascinated,

as Leonardo was, with

mystery.