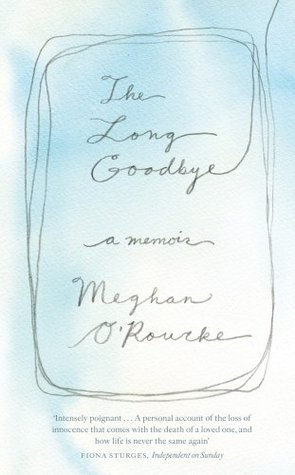

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The bereaved cannot communicate with the unbereaved. IRIS MURDOCH

Nothing prepared me for the loss of my mother. Even knowing that she would die did not prepare me. A mother, after all, is your entry into the world. She is the shell in which you divide and become a life. Waking up in a world without her is like waking up in a world without sky: unimaginable.

When we talk about love, we go back to the start, to pinpoint the moment of free fall. But this story is the story of an ending, of death, and it has no beginning. A mother is beyond any notion of a beginning. That’s what makes her a mother: you cannot start the story.

I had gone dead inside. Psychiatrists, I read later, call this “numbing out.” When you can’t deal with the pain of a situation, you shut down your emotions. I knew I was sad, but I knew it only intellectually. I couldn’t feel it yet. It was like when you stay in cold water too long. You know something is off but don’t start shivering for ten minutes.

I was irrevocably aware that the Person Who Loved Me Most in the World was about to be dead. Of course, I had my father, too. But fathers love in different ways than mothers do.

My mother was dying, and the only person I wanted to talk to about my despair over it was her.

When people are hurting they cannot always comfort one another; it was true of us. We had the same injury and different symptoms.

The world seemed to push me away. I felt that I was pacing in the chilly dark outside a house with lit-up windows, wishing I could go inside. But I also felt that the people in those rooms were shutting out the news of a distant, important war, a war I had just returned from. Consumed by the question of what it means to be mortal, I looked around and thought, We are all going to die.

I was reminded of an untitled poem by Franz Wright, which reads in full: I basked in you; I loved you, helplessly, with a boundless tongue-tied love. And death doesn’t prevent me from loving you. Besides, in my opinion you aren’t dead. (I know dead people, and you are not dead.)

“Your mother is not there,” he explained. “And we are dealing with her absence. It makes us feel, I think, a loss of confidence—a general loss, an uncertainty about what we can rely on.”

I also felt that if I told the story of her death, I could understand it better, make sense of it—perhaps even change it. What had actually happened still seemed implausible: A person was present your entire life, and then one day she disappeared and never came back. It resisted belief. Even when a death is foreseen, I was surprised to find, it still feels sudden—an instant that could have gone differently.

mother died. In the dreams, when I said this, I experienced the shock all over again: My mother had died. It was hard to take it in; she was the very being who once contained me.

If children learn through exposure to new experiences, mourners unlearn through exposure to absence in new contexts. Grief requires acquainting yourself with the world again and again; each “first” causes a break that must be reset.

And so you always feel suspense, a queer dread—you never know what occasion will break the loss freshly open.

What are we to do with the knowledge that we die? What bargain do you make in your mind so as not to go crazy with fear of the predicament, a predicament none of us knowingly chose to enter? You can believe in God and heaven, if you have the capacity for faith. Or, if you don’t, you can do what a stoic like Seneca did, and push away the awfulness by noting that if death is indeed extinction, it won’t hurt, for we won’t experience it. “It would be dreadful could it remain with you; but of necessity either it does not arrive or else it departs,” he wrote.

I thought I was prepared for my mother’s death. I knew it would happen. Yet the reality of her being dead was so different from her death.

Yesterday, while I was brushing my teeth, I raised my face to the mirror and unexpectedly saw myself. And I thought: I am becoming someone whose mother is dead. Then a cool sadness flooded me. It was true. I was getting used to her being dead. My mother was gone. And I: letting her go.

AFTER A LOSS, you have to learn to believe the dead one is dead. It doesn’t come naturally.

Three-quarters of a year after a loss, the hardest part is the permanently transitional quality: you are neither accustomed to it nor in its fresh pangs. You feel you will always be wading the river, your legs burning with exhaustion.

And as I was walking I thought: I will carry this wound forever. It’s not a question of getting over it or healing. No; it’s a question of learning to live with this transformation. For the loss is transformative, in good ways and bad, a tangle of change that cannot be threaded into the usual narrative spools. It is too central for that. It’s not an emergence from the cocoon, but a tree growing around an obstruction.

ONE OF THE GRUBBY TRUTHS about a loss is that you don’t just mourn the dead person, you mourn the person you got to be when the lost one was alive. This loss might even be what affects you most. Jim kept saying, “I am sorry for all the things your mother is going to miss”—and he would list them. And I would think: I am a sorry excuse for a daughter. I just think about how I miss her. I’m sorry for myself, sorry about losing a life where I always had a mom to go to. Whatever the case, in grief you’re not just reconstituting the lost person, recalling her, then letting her go—you’re having to

...more

I love C. S. Lewis’s metaphor: A loss is like an amputation. If the blood doesn’t stop gushing soon after the operation, then you will die. To survive means, by definition, that the blood has stopped. But the amputation is still there.