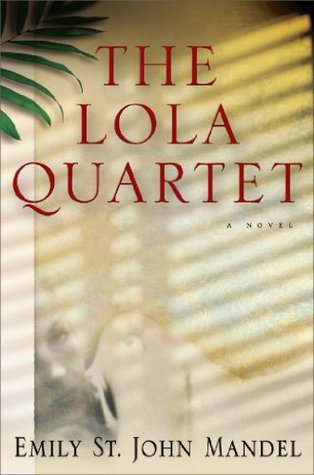

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

But now he woke in the mornings in a soundproofed house as closed as a space station, cool air humming through a vent in the wall.

I love how, now on my third Emily book, I keep feeling that they’re all set in the same, or just slightly different parallel universes... same feelings, same imagery, same beautiful loneliness...

“What’s this music we’re listening to?” Morelli asked. “They’re called Baltica,” Anna said. “I think they’re from Canada.” The CD played on the stereo on top of the fridge, quietly so it wouldn’t wake Chloe. Baltica’s sound made her think of snow. A high clear beat with electronic strings in the background sometimes and gentle static, repetitive echoing lyrics if there were any lyrics at all, I always come to you, come to you, come to you in the background while she beat eggs in a bowl with a fork.

“It sounds like a nice idea,” Anna said. “I used to spend a lot of time with a jazz quartet in high school.” “Did you play?” “No,” she said. “My friends and my sister did.” Were they her friends? She’d slept with two of them and managed to betray both, put the third in danger by showing up at his dorm room, left the state without telling her sister. The pan blurred before her eyes. She blinked hard and flipped the omelette.

“Why don’t we just go to your uncle’s place?” “Because he lives in a small apartment and my friend’s got an entire house to himself.” “What’s your friend’s name?” she asked on the way up the driveway. Daniel was walking ahead of her with the bags. “Paul,” he said. “We worked together when I was here last summer.”

“Well, we knew Gloria was getting foreclosed—” “But what kind of a real estate agent takes pictures of someone else’s child? Asks her questions? They’ve found us, Sasha, they’ve found us—” “No one’s found us,” Sasha said. “There’s no they.” She was looking at Daniel now. “There’s just a him. One person. Who probably hasn’t left Utah.” Daniel was expressionless. “Who probably has no idea where you are and probably stopped looking years ago. Everything will be fine. Listen, Daniel’s here.” Anna made an indecipherable noise. “Let me talk to him about this.” “What the hell can he do?” Anna asked.

...more

I don’t get this: for this whole book nobody has communicated to anybody else for shit. And now all of a sudden Anna, Sasha and Daniel are talking about everything? Why aren’t they including Gavin?

“Don’t stop,” Gavin said. So Jack continued, eased back into another long loop of melody. George Gershwin’s “Summertime.” Music for a place where it was almost always summer. He knew an arrangement that kept the song looping around and around and he improvised inside it, leaving the melody and wandering away and then coming back to the tune again, and the living is easy, long and slow and meandering, soft and low under the orange tree. Jack always imagined a singer’s voice when he played this song, a woman soothing a child to sleep on a porch in the southern lands that lay north of Florida,

...more

The singing doesn’t start till halfway through, and then when it gets to that part about rising up singing, it’s like—” Like a thunderstorm, like disintegration, like a soul rising up, but Jack felt stupid saying these things aloud.

“I’m going to play again,” Jack said. Playing, he had realized, was something that would preclude talking. He wanted to fall back into music and rest for a while. He started playing “Summertime” at half-speed, almost a dirge, slow light all around him, and when he looked up some time later Gavin was gone. He drifted alone in his lawn chair on the grass.

“Someone came to my mother’s house and took a picture of the kid.” Deval leaned forward, his elbows on his knees, and slowly lowered his face into his hands. “Your mother? Gloria Jones, that woman she was staying with a few months back?” “Gloria. Yes.” “A picture. That’s what started this whole thing?” He felt ill. The picture of Chloe was stuck to his fridge with a magnet.

address myself to the police officer watching me from behind a high blue countertop, I say the words that change everything: I have information about a murder. I make statements, I name names. I do the technically correct thing, the right thing, the thing a law-abiding citizen does in the presence of a crime.

His lips moving with the words of a letter that he would transcribe some days later in Chicago, a letter that he would write but never send: I wanted to find you, dear Chloe, I wanted to help, but in the end the best I could do for you was to leave you in peace. I love you. I’ll never know you. I’ll always wonder who you are.