More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

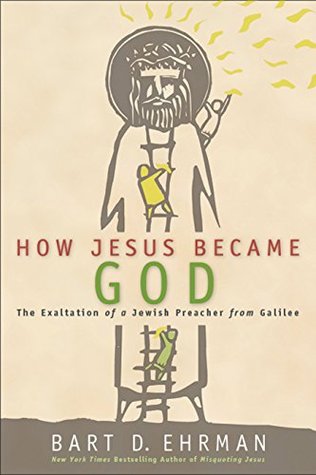

As a historian I am no longer obsessed with the theological question of how God became a man, but with the historical question of how a man became God.

there are passages in which the king of Israel is referred to as divine, as God. Hebrew Bible scholar John Collins points out that this notion ultimately appears to derive from Egyptian ways of thinking about their king, the Pharaoh, as a divine

it is important to stress a fundamental point. History, for historians, is not the same as “the past.” The past is everything that has happened before; history is what we can establish as having happened before, using historical forms of evidence. Historical evidence is not and cannot be based on religious and theological assumptions that some, but not all, of us share.

Bruce Metzger showed so elegantly in his article “Names for the Nameless.”7 Here he showed all the traditions of people who were unnamed in New Testament stories receiving names later; for example, the wise men are named in later traditions, as are priests serving on the Sanhedrin when they condemned Jesus and the two robbers who were crucified with him.

The other matter of uncertainty is when belief in Jesus’s resurrection and exaltation began. The tradition, of course, states that it began on the third day after he died. But as I argued in the analysis of 1 Corinthians 15:3–5, the idea that Jesus rose on the “third day” was originally a theological construct, not a historical piece of information.

In Brown’s view this chronological sequencing of the Gospels may well indeed be how Christians developed their views. Originally, Jesus was thought to have been exalted only at the resurrection; as Christians thought more about the matter, they came to think that he must have been the Son of God during his entire ministry, so that he became the Son of God at its outset, at baptism; as they thought even more about it, they came to think he must have been the Son of God for his entire life, and so he was born of a virgin and in that sense was the (literal) Son of God; and as they thought about

...more

Still, historians do continue to use the terms orthodoxy, heresy, and heterodoxy to describe the early struggles over truth. This is not because historians know which side, ultimately, was right, but because they know which side, ultimately, prevailed. The side that eventually won the most converts and decided what Christians should believe is called “orthodox,” because it established itself as the dominant view and thus declared it was right. A “heresy” or a “heterodoxy,” from a modern historical perspective, is simply a view that lost the debate.

This is one of the hard-and-fast ironies of the Christian tradition: views that at one time were the majority opinion, or at least that were widely seen as completely acceptable, eventually came to be left behind; and as theology moved forward to become increasingly nuanced and sophisticated, these earlier majority opinions came to be condemned as heresies.