More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

May 5 - May 8, 2020

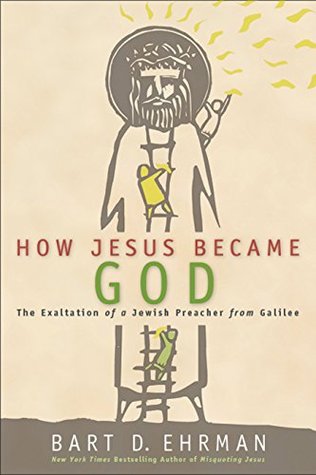

How did a crucified peasant come to be thought of as the Lord who created all things? How did Jesus become God?

Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke—in which Jesus never makes explicit divine claims about himself—portray Jesus as a human but not as God,

The problem is that most ancient people—whether Christian, Jewish, or pagan—did not have this paradigm. For them, the human realm was not an absolute category separated from the divine realm by an enormous and unbridgeable crevasse. On the contrary, the human and divine were two continuums that could, and did, overlap.

One of my theses will be that a Christian text such as the Gospel of Mark understands Jesus in the first way, as a human who came to be made divine. The Gospel of John understands him in the second way, as a divine being who became human. Both of them see Jesus as divine, but in different ways.

how Jesus came to be considered God. The short answer is that it all had to do with his followers’ belief that he had been raised from the dead.

The debates over the nature of Christ were not resolved by the end of the third century but came to a head in the early fourth century after the conversion of the emperor Constantine to the Christian faith.

As a philosopher Apollonius taught that the human soul is immortal; the flesh may die, but the person lives on.

will become clear in the following chapters that Jesus was not originally considered to be God in any sense at all, and that he eventually became divine for his followers in some sense before he came to be thought of as equal with God Almighty in an absolute sense. But the point I stress is that this was, in fact, a development.

there were beings who lived not on earth but in the heavenly realm and who had godlike, superhuman powers, even if they were not the equals of the ultimate God himself. In the Hebrew Bible, for example, there are angels, cherubim, and seraphim—attendants upon God who worship him and administer his will (see, for example, Isa. 6:1–6).

So Jewish texts speak of the great angels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. These are divine powers far above humans, though far below God as well.

within Judaism there was understood to be a continuum of divine beings and divine power, comparable in many ways to that which could be found in paganism.

But one thing they all agree on: Jesus did not spend his ministry declaring himself to be divine.

The problems with Paul are that he didn’t actually know Jesus personally and that he doesn’t tell us very much about Jesus’s teachings, activities, or experiences.

(Paul, by the way, never says that Jesus declared himself to be divine.)

But in fact the books were written anonymously—the authors never identify themselves—and they circulated for decades before anyone claimed they were written by these people. The first certain attribution of these books to these authors is a century after they were produced.

The stories were being told by word of mouth, year after year, decade after decade, among lots of people in different parts of the world, in different languages, and there was no way to control what one person said to the next about Jesus’s words and deeds.

What is it that made Jesus so special? In fact, as we will see, it was not his message. That did not succeed much at all. Instead, it helped get him crucified—surely

Belief in Jesus’s resurrection changed absolutely everything. Such a thing was not said of any of the other apocalyptic preachers of Jesus’s day, and the fact that it was said about Jesus made him unique.

Belief in the resurrection is what eventually led his followers to claim that Jesus was God.

If they fled on Friday, they would not have been able to travel on Saturday, the Sabbath; and since it was about 120 miles from Jerusalem to Capernaum, their former home base, it would have taken a week at least for them to get there on foot.

elite Roman families, it was the adopted son who really mattered, not the sons born of the physical union of a married couple.

The adopted son on the other hand—who was normally adopted as an adult—was adopted precisely because of his fine qualities and excellent potential. He was made great because he had demonstrated the potential for greatness, not because of the accident of his birth.

When the earliest Christians talked about Jesus becoming the Son of God at his resurrection, they were saying something truly remarkable about him. He was made the heir of all that was God’s. He exchanged his status for the status possessed by the Creator and ruler of all things. He received all of God’s power and privileges. He could defy death. He could forgive sins. He could be the future judge of the earth. He could rule with divine authority. He was for all intents and purposes God.

the oldest Gospel, Mark, seems to assume that it was at his baptism that Jesus became the Son of God; the next Gospels, Matthew and Luke, indicate that Jesus became the Son of God when he was born; and the last Gospel, John, presents Jesus as the Son of God from before creation.

as they thought even more about it, they came to think he must have been the Son of God for his entire life, and so he was born of a virgin and in that sense was the (literal) Son of God;

Different Christians in different churches in different regions had different views of Jesus, almost from the get-go.

when scribes were copying their texts of Luke in later centuries, the view that Jesus was made the Son at the baptism was considered not just inadequate, but heretical.

For the Christians, God was transcendent, remote, “up there”—not one to have sex with beautiful girls. At the same time, something somewhat like the pagan myths appears to lie behind the birth narrative found in the Gospel of Luke.

It is God, not Joseph, who will make Mary pregnant, so the child she bears will be God’s offspring. Here, Jesus becomes the Son of God not at his resurrection or his baptism, but already at his conception.

Instead, according to Matthew, the reason Jesus’s mother was a virgin was so that his birth could fulfill what had been said by a spokesperson of God many centuries earlier, when the prophet Isaiah in the Jewish scriptures wrote, “A virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and his name shall be called Immanuel” (Isa. 7:14). Matthew quotes this verse and gives it as the reason for Jesus’s unusual conception—it was to fulfill prophecy (Matt. 1:23).

If you read Isaiah 7 in its own literary context, it is clear that the author is not speaking about the messiah at all. The situation is quite different.

Matthew read the book of Isaiah not in the original Hebrew language, but in his own tongue, Greek. When the Greek translators before his day rendered the passage, they translated the Hebrew for word young woman (alma) using a Greek word (parthenos) that can indeed mean just that but that eventually took on the connotation of a “young woman who has never had sex.”

In these two Gospels, Jesus comes into existence at the moment of his conception. He did not exist before.

We believe in one God, the Father, the Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all that is, seen and unseen. In my experience, many Christians who say these words have no idea why they are there. Why, for example, would the creed stress that there is “one God”? People today either believe in God or they don’t. But who believes in two Gods? Why say there is only one? The reason has to do with the history behind the creed.

Every one of these statements was put into the creed to ward off heretics who had different beliefs, for example, that Christ was a lesser divine being from God the Father, or that he was not really a human, or that his suffering was not important for salvation, or that his kingdom would eventually come to an end—all of them notions held by one Christian group or another in the early centuries of the church.

of the entire creed, I can say only one part in good faith: “he was crucified under Pontius Pilate; he suffered death and was buried.”

if you put together all the orthodox affirmations, the result is the ortho-paradox: Christ is God; Christ is a man; but he is one being, not two.

finally I came to think of him as a human being who was not different in nature from any other human being. The Christians exalted him to the divine realm in their theology, but in my opinion, he was, and always had been, a human.

As an agnostic, I now think of Jesus as a true religious genius with brilliant insights. But he was also very much a man of his time.

Jesus himself would be the ruler of this kingdom, with his twelve disciples serving under him. And all this was to happen very soon—within his own generation.

do not think that there are supernatural powers of evil who are controlling our governments or demons who are making our lives miserable; I do not think there is going to be a divine intervention in the world in which all the forces of evil will be permanently destroyed; I do not think there will be a future utopian kingdom here on earth ruled by Jesus and his apostles.

do think there is good and evil; I do think we should all be on the side of good; and I do think we should fight mightily against all that is evil.

Most Christians today do not realize that they have recontextualized Jesus. But in fact they have. Everyone who either believes in him or subscribes to any of his teachings has done so—from

Nicea and its creed were not the end of the story, but the beginning of a new chapter. For one thing, the defeat

the Council of Constantinople in 381. At this council the decisions of Nicea were restated and reaffirmed, and Arianism came to be a marginalized minority view widely deemed heretical.

If the Jews killed Jesus, and Jesus was God, does it not follow that the Jews had killed their own God?1 This was in fact a view held in orthodox circles long before the conversion of Constantine.