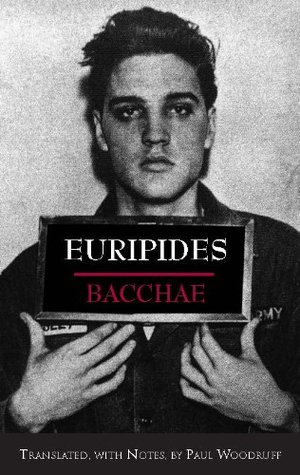

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

There were also patriotic reasons for setting disaster stories in Thebes. Thebes is Athens’ inland neighbor, but the Thebans sided against Athens twice—with Persia in the Persian Wars, and with Sparta in the war that was winding down to Athens’ defeat at the very time Euripides was writing the play.

Dionysus plays simultaneously on Pentheus’ explicit commitment to doing the right thing as a soldier and his suppressed desire to explore the more vulnerable feminine side of his personality.

First, we meet the god himself

Second, we hear of him from the chorus, to whom he is a source of delight, release, and freedom, at the same time as he is a fearsome power to whom they pray for justice in their distress.

Third, we see him as Pentheus does, as an effeminate foreigner with a gift for clever speaking.

When Dionysus speaks in disguise as a young man he works through double meanings or ambiguities. These allow him to fulfill Pentheus’ expectations of a clever speaker while maintaining the calm authority of a god. When he speaks as a god he is clear and direct, pedantic, unfeeling, and strong. During

The kind word for this status is xenai (guests, strangers), but they are also called barbaroi {xxvi} (foreigners). Their outlandishness would be visible in their costumes, though the basics of their Bacchic paraphernalia would be familiar to Athenians.

The members of this chorus are not agents in the tragic action. They observe and comment, and their comments are wise with the common sense of good Athenian citizens.

Euripides makes little of this in the Bacchae, except to have Tiresias deny that his prognostication is based on his art.

A boy between sixteen and twenty years old,18 Pentheus is at a transitional age, when most boys are negotiating the change from a passive to an active role in society, about the time of military training. We cannot be sure what he was like before his cousin Dionysus came to town; perhaps he has already been crazed by Dionysus into a state in which he can see no further than resistance to the new cult.

In the end he will do what a good soldier does: give up his life for his people. His death will satisfy the anger of Dionysus against Thebes, and his sacrifice will be marked by some of the features of {xxix} the killing of a scapegoat, although dying at the hands of his mother brings a dreadful pollution to the royal family, which now must go into exile.

From ancient times, many students of Euripides have believed that he attacked religion in his earlier plays (p. xviii), was severely criticized for these attacks,20 and came to repent in old age, when he wrote the Bacchae. The play, on this view, serves as Euripides’ recantation (“palinode”) to the gods and his defense to the people of Athens on an unofficial charge of irreverence. The interpretation prevailed until late in the nineteenth century. In this century, however, scholars have almost unanimously rejected the idea that Euripides had such a change of heart.

Close study of earlier plays shows that he had always recognized the power of the irrational and the failure of rationalism to defeat it.21 Modern critics have also pointed out, rightly, that there is nothing in the Bacchae to counter the moral criticism of mythological religion that found expression in Euripides’ earlier plays.

the Bacchae contains a uniquely sustained attack against the rationalism of the New Learning,

Nietzsche, on weak grounds, accepts a version of the recantation interpretation.22 His well-known theory about the creative tension between Apollo and Dionysus is largely based on his reading of this play.

Nietzsche believes that tragic art arises only when each of the two gods comes somehow to speak the language of the other; the Apollinian need for control and individuation in ancient Greek culture merely shows how powerful is the undercurrent of the irrational, and the two gods are in balance at the moment of tragic culture in Greece.

Dionysus-worship may be seductive as seen through the eyes of the chorus in the beginning, but by the end of the play this impression should be more than balanced by a sense of the horrible dangers that attend on its extravagant joys

“The play is not in any way an attack, as some have supposed, on Dionysiac cult. That the citizens of Athens continue to perform collective cult … is essential for the cohesion of the polis”

He believes, however, that the play may have helped Athenians resolve their tensions about the arrival of new foreign cults (p. 52).

“The final condemnation of these bleak ingenuities,” writes Dodds (1960, p. l), “is, for me at least, that they transform one of the greatest of all tragedies into a species of donnish witticism (a witticism so illcontrived {xxxiii} that it was twenty-three centuries before anyone saw the point).”25

“The moral of the Bacchae,” he says elsewhere, “is that we ignore at our peril the demand of the human spirit for Dionysiac experience…

Observations of psychological truth in the play, however, should not be mistaken for interpretations of the play. Certainly, the play warns against trying to suppress the irrational; but the grounds it repeatedly cites for this warning are religious, not psychological, and the goal the chorus praises for human life is not mental health as such, but the well-being that flows from reverence.

Euripides was conscious of the ambivalence of Dionysus, of the contrast between the god of pleasant ecstasy on the one {xxxv} hand, and the god of destructive powers on the other, and of the moral and social instability of those who excessively devoted themselves to him.

In civic life, if Seaford is right, celebration of Dionysus is essential to the unity of the Greek city, so that the destruction of Pentheus is “a social necessity,” and the grisly end of the play would justify neither religious pessimism nor an attack on religion.

“Dionysus and Pentheus seem to embody the anger of jealous city-states,” he observes, reading into fifth-century attitudes the harsh judgments of Thucydides (1998, p. 18).

The question I think most helpful is this one: Why does the play make such an effort to skewer the wisdom of intellectuals? There are obvious passages from the chorus, and there is Pentheus’ criticism of Dionysus; but there is also the bizarre treatment of Tiresias.

The most likely explanation is that Euripides has a bone to pick with the New Learning, and this is confirmed many times in the remainder of the play.

only when Pentheus sees the god as a bull is he beginning to see correctly

We in the audience share Pentheus’ bad vision: Dionysus shows himself as a sophist to those who see his bad side. Most importantly, the chorus sees those who oppose them in Thebes entirely as an unholy alliance of ambition, innovation, and {xl} clever sophistication parading falsely as wisdom.

Pentheus is a naive young man clinging to traditional ideas and desperately afraid of innovations that would upset the balance of control men have over women. Pentheus is as...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Why then does the play repeatedly attack the New Learning?

The wisdom of old age, after all, is like the wisdom of initiation—calm, accepting, and based on a sequence of experiences. It is not at all like the brilliant techniques of argument and persuasion that can be taught to the young to further their ambitions.

Initiation occurs in many cults, but is especially appropriate in the case of Dionysus, the god who has a gift for combining opposites.

Dionysus is a god who takes human form, a powerful male who looks soft and feminine, a native of Thebes who dresses as a foreigner.

He does not merely cross boundaries, he blurs and confounds them, makes nonsense of the lines between Greek and foreign, between female and male, between powerful and weak, between savage {xli} and civilized.

We might say, then, that Dionysus appears mysterious because he is mysterious, because it is his special role to undermine the boundaries set by human culture.

But Dionysus is not a god of mystery; he is the god of what is known as a mystery religion.

When Pentheus asks, “You say you saw the god clearly. What did he look like?” Dionysus in human form answers, “Whatever way he wanted. I had no control of that” (477–78). Initiates are beyond the level of appearances; they know Dionysus simply for the power that he is.

The point, rather, is that clear understanding comes only by way of initiation, and not by active intellectual efforts. If a deity strikes you as mysterious, that is because you have not been initiated into his or her mysteries. The mystery will only deepen if you try to lead yourself to a solution.

The play keeps before us a running contrast between wisdom and cleverness, a contrast by which modern scholarship (as Nietzsche saw) would be on the wrong side.

I have changed from divine to human form, and here I am.

That is how angry Hera was at my mother—violent, deathless rage.

this ivy-covered spear—

That is why I have stung these women into madness, goaded them outdoors, made them live in the mountain, struck out of their wits, forced to wear my cult’s panoply.

This city must fully learn its lesson, like it [40] or not, since it is not initiated in my religion. Besides, I must defend my mother, Semélê, and make people see I am a god, born by her to Zeus.

I’ll show him I am truly god,

once I’ve put this place in order, I’ll [50] turn to another country, reveal myself there.

It’s to do this that I have taken human form and changed myself into a man.

mountain, I hasten my sweet labor for the Thunderer.

You, on the road! You, on the road! You, in the houses!