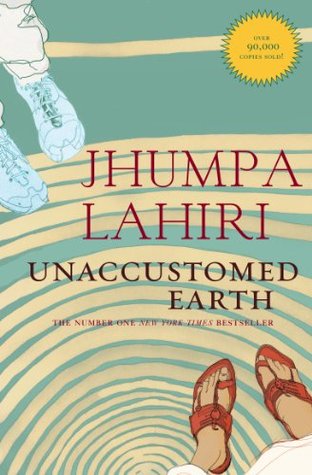

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It was not passion that was driving him, at seventy, to be involved, however discreetly, however occasionally, with another woman. Instead it was the consequence of being married all those years, the habit of companionship.

She’d worked for as long as he could remember. Even in high school, in spite of his and his wife’s protests, she’d insisted, in the summers, on working as a busgirl at a local restaurant, the sort of work their relatives in India would have found disgraceful for a girl of her class and education.

While her father was in the shower, she made tea. It was a ritual she liked, a formal recognition of the day turning into evening in spite of the sun not setting.

But death, too, had the power to awe, she knew this now—that a human being could be alive for years and years, thinking and breathing and eating, full of a million worries and feelings and thoughts, taking up space in the world, and then, in an instant, become absent, invisible.

He didn’t want to live again in an enormous house that would only fill up with things over the years, as the children grew, all the things he’d recently gotten rid of, all the books and papers and clothes and objects one felt compelled to possess, to save. Life grew and grew until a certain point. The point he had reached now.

The information fell between them, valuable for the years he’d kept it from her, negligible now that he’d told.

“That’s the problem with this country,” her mother said. “Too many freedoms, too much having fun. When we were young, life wasn’t always about fun.”