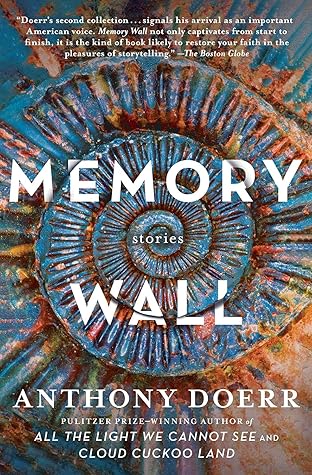

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

His hair smells like dust, pencil shavings, and smoke. Rain murmurs against the roof.

The lights of a chandelier are momentarily trapped inside.

Memories twist slowly through Luvo’s thoughts: Alma as a six-year-old, a dining room, linen tablecloths, the laughter of grown-ups, the soft hush of servants in white shirts bringing in food. Alma sheathing the body of an earthworm over the point of a fishhook. A faintly glowing churchyard, and Alma’s mother’s bony fingers wrapped around a steering wheel. Bulldozers and rattling buses and gaps in the security fences around the suburbs where she grew up. Buying a backlot brandy called white lightning from Xhosa kids half her age.

hears Harold Konachek whispering as if from the grave: We all swirl slowly down into the muck. We all go back to the mud. Until we rise again in ribbons of light.

To say a person is a happy person or an unhappy person is ridiculous. We are a thousand different kinds of people every hour.”

As he lies in his sleeping bag on his third night he can hear an almost imperceptible rustling: night flowers unveiling their petals to the moon. When he is very quiet, and his mind has stilled the chewing and whirling and sucking of his fears, he imagines he can hear the coursing of water deep beneath the mountains, and the movements of the roots of the plants as they dive toward it—it sounds like the voices of men, singing softly to one another. And beyond that—if only he could listen even more closely!—there was so much more to hear: the supersonic screams of bats, and, on the most distant

...more

Maybe the river is already beginning to slack, to back up and rise. Maybe ghosts pour out of the Earth, out of the mouths of tombs up and down the gorges, out of the tips of twigs at the ends of branches. The fireflies tap against the glass. More than anything, she thinks, I’ll be sad to see the speed go out of the water.

The urge to know scrapes against the inability to know. What was Mrs. Sabo’s life like? What was my mother’s? We peer at the past through murky water; all we can see are shapes and figures. How much is real? And how much is merely threads and tombstones?

Why, Esther wonders, do any of us believe our lives lead outward through time? How do we know we aren’t continually traveling inward, toward our centers? Because this is how it feels to Esther when she sits on her deck in Geneva, Ohio, in the last spring of her life; it feels as if she is being drawn down some path that leads deeper inside, toward a miniature, shrouded, final kingdom that has waited within her all along.

Within the wet enclosure of a single mind a person can fly from one decade to the next, one country to another, past to present, memory to imagination.

She reaches for her husband’s shape in the night; she clings to him.

Every hour, Robert thinks, all over the globe, an infinite number of memories disappear, whole glowing atlases dragged into graves. But during that same hour children are moving about, surveying territory that seems to them entirely new. They push back the darkness; they scatter memories behind them like bread crumbs. The world is remade.