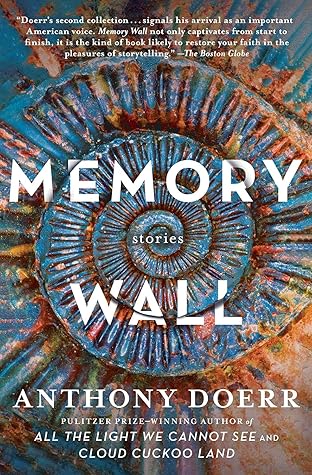

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

When it worked, it must have been like descending into a pitch-black cellar for a jar of preserves, and finding the jar waiting there, cool and heavy, so she could bring it up the bowed and dusty stairs into the light of the kitchen. For a while it must have worked for Alma, anyway; it must have helped her believe she could fend off her inevitable erasure.

It has not worked as well for Roger and Luvo. Luvo does not know how to turn the wall to his ends; it will only show him Alma’s life as it wishes. The cartridges veer toward and away from his goal without ever quite reaching it; he founders inside a past and a mind over which he has no control.

An old woman’s life becomes a young man’s. Memory-watcher meets memory-keeper.

Luvo takes his big duffel and four bottles of water from the backseat and steps out into the darkness. The man looks at him a full half-minute before pulling off. It’s warm in the moonlight but Luvo stands shivering for a moment, holding his things, and then walks to the edge of the road and peers over the retaining wall into the shadows below. He finds a thin path, cut into the slope, and hikes maybe two hundred meters north of the road, pausing every now and then to watch the twin red taillights of the salesman’s Honda as it eases up the switchbacks high above him toward the top of the pass.

Why did he think he could find a fossil out here? A fifteen-year-old boy who knows only adventure novels and an old woman’s memories? Who has never found a fossil in his life?

This is not real suffering, she tells herself. This is only a matter of reprogramming her picture of the future. Of understanding that the line of descendancy is not continuous but arbitrary.

She marvels at how having her son at her table can be a deep pleasure and at the same time a thorn in her heart.

Stories, only stories. Not every story is seeded in truth. Still, she lies in bed and falls through the surfaces of nightmares: The river climbs the bedposts; water pours through the shutters. She wakes choking.

There are things here that will make your life easier. What I wanted to say is that you don’t have to remain loyal to one place all your life.

Maybe, she thinks, I’ve got this all wrong. Maybe at some point a person should stop accumulating judgments and start letting them go.

“Maybe,” he says, “a place looks different when you know you’re seeing it for the last time. Or maybe it’s knowing no one will ever see it again. Maybe knowing no one will see it again changes it.”