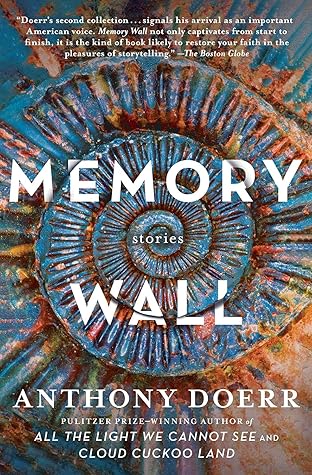

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

You have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realize that memory is what makes our lives. Life without memory is no life at all, just as an intelligence without the possibility of expression is not really an intelligence. Our memory is our coherence, our reason, our feeling, even our action. Without it, we are nothing. —LUIS BUÑUEL, MY LAST SIGH

Memories are located not inside the cells but in the extracellular space.

But what about beauty? What about love? What about feeling a deep humility at our place in time? Where’s the room for that?”

say a person is a happy person or an unhappy person is ridiculous. We are a thousand different kinds of people every hour.”

And beyond that—if only he could listen even more closely!—there was so much more to hear: the supersonic screams of bats, and, on the most distant tablelands, the subsonic conversations of elephants in the game reserves, grunts and moans so deep they carry between animals miles apart, forced into a few isolated reserves, like castaways on distant islands, their calls passing through the mountains and then shuttling back.

Dr. Amnesty’s cartridges, the South African Museum, Harold’s fossils, Chefe Carpenter’s collection, Alma’s memory wall—weren’t they all ways of trying to defy erasure? What is memory anyway? How can it be such a frail, perishable thing?

“Memory builds itself without any clean or objective logic: a dot here, another dot here, and plenty of dark spaces in between. What we know is always evolving, always subdividing. Remember a memory often enough and you can create a new memory, the memory of remembering.”

“Nothing lasts,” Harold would say. “For a fossil to happen is a miracle. One in fifty million. The rest of us? We disappear into the grass, into beetles, into worms. Into ribbons of light.”

person can get up and leave her life. The world is that big. You can take a $4,000 inheritance and walk into an airport and before your heartache catches up with you, you can be in the middle of a desert city listening to dogs bark and no one for three thousand miles will know your name.

Nothingness is the permanent thing. Nothingness is the rule. Life is the exception.

Where do memories go once we’ve lost our ability to summon them?

Memory is a house with ten thousand rooms; it is a village slated to be inundated.

Every stone, every stair, is a key to a memory. Here

Mostly she listens to the old man’s voice in the darkness, his sentences parceling out one after another until his frail body beside her seems to disappear in the darkness and he is only a voice, a schoolteacher’s fading elocution.

Everything accumulates a terrible beauty. Dawns are long and pink; dusks last an hour. Swallows swerve and dive and the stripe of sky between the walls of the gorge is purple and as soft as flesh. The fireflies float higher up on the cliffs, a foam of green, as if they know, as if they can sense the water coming.

Twenty thousand days and nights in one place, each layered and trapped and folded on top of the last, the creases in her hands, the aches between her vertebrae. Embryo, seed coat, endosperm: What is a seed if not the purest kind of memory, a link to every generation that has gone before it?

Every memory everyone has ever had will eventually be underwater. Progress is a storm and the wings of everything are swept up in it.

Seeds are the dreams plants dream while they sleep. Seeds

Her mother used to say seeds were links in a chain, not beginnings or endings, but she was wrong: Seeds are both beginnings and ends—they are a plant’s eggshell and its coffin. Orchards crouch invisibly inside each one.

We go round the world only to come back again. A seed coat splits, a tiny rootlet emerges. On the news a government official denies reports of cracks in the dam’s ship locks.

Every hour the thought floats to the surface: If we’re all going to end up happy together in Heaven then why does anyone wait? Every hour the Big Sadness hangs behind my ribs, sharp and gleaming, and it’s all I can do to keep breathing.

Everything, all of it, our junk, our dregs, our memories. And I’ve got the family poodle and three duffel bags of too small clothes and four photo albums, but no one left who can flesh out any of the photos.

how just because you don’t see something doesn’t mean you shouldn’t believe in it.

I like to think she’s remembering other trips down the river, other afternoons in the sun.

begin to think maybe Grandpa Z is right, maybe sometimes the things we think we see aren’t really what we see. But here’s the surprising thing: It doesn’t bother me.

Going out on the Nemunas is sort of like that. You come down the path and step through the willows and it’s like seeing the lights in the world come back on.

Emily Dickinson’s mom was like that. Of course, Emily Dickinson wound up terrified of death and wore only white clothes and would only talk to visitors through the closed door of her room.

I wonder about how memories can be here one minute and then gone the next. I wonder about how the sky can be a huge, blue nothingness and at the same time it can also feel like a shelter.

toothed smile as if whatever was on the other end of her fishing line has just pulled her back into the present for a minute and in the silence I feel my mom is here, together with me, under the Lithuanian sunrise, both of us with decades left to live.

So what, Grandpa, you don’t believe in anything you can’t see? You believe we don’t have souls? You put a cross on every headstone you make, but you think the only thing that happens to us when we die is that we turn into mud?

Dickinson biography when she says, “To live is so startling it leaves little time for anything else.” People still remember Emily Dickinson said that, but when I try to remember a sentence Mom or Dad said I can’t remember a single one. They probably said a million sentences to me before they died but tonight it seems all I have are prayers and clichés.

At the end the narrator says the tribe’s old language has a word for standing in the rain looking at the back of a person you love.

It’s just a big lump of memory at the bottom of the River Nemunas.

The urge to know scrapes against the inability to know. What was Mrs. Sabo’s life like? What was my mother’s? We peer at the past through murky water; all we can see are shapes and figures.

We wait until everyone who knew us when we were children has died. And when the last one of them dies, we finally die our third death.”

When she opens her eyes, a crow is sitting on a branch just outside the window. It turns an eye toward her, cocks its head, blinks. Esther walks toward it, sets her palm against a pane. Does she see it? Just there? Something glowing between its feathers? Some other world folded inside this one?

Draw the darkness, Esther thinks, and it will point out the light which has been in the paper all the while. Inside this world is folded another.

Why, Esther wonders, do any of us believe our lives lead outward through time? How do we know we aren’t continually traveling inward, toward our centers? Because this is how it feels to Esther when she sits on her deck in Geneva, Ohio, in the last spring of her life; it feels as if she is being drawn down some path that leads deeper inside, toward a miniature, shrouded, final kingdom that has waited within her all along.

“The only thing I’ve learned so far, Esther,” she says, “is that things can always get worse.”

Memory becomes her enemy. Esther works on maintaining her attention only in the present; there is always the now—an endlessly adjusting smell of the wind, the shining of the stars, the deep five-call chirrup chirrup of the cicadas in the park. There is the now that is today falling into the now that is tonight: dusk on the rim of the Atlantic, the flicker of the movie screen, a submergence of memory, a tanker cleaving imperceptibly across the horizon.

Every tree, every post of the garden fence, is a candle to a memory, and each of those memories, as it rises out of the snow, is linked to a dozen more.

Every hour, Robert thinks, all over the globe, an infinite number of memories disappear, whole glowing atlases dragged into graves. But during that same hour children are moving about, surveying territory that seems to them entirely new. They push back the darkness; they scatter memories behind them like bread crumbs. The world is remade.

You bury your childhood here and there. It waits for you, all your life, to come back and dig it up.