More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

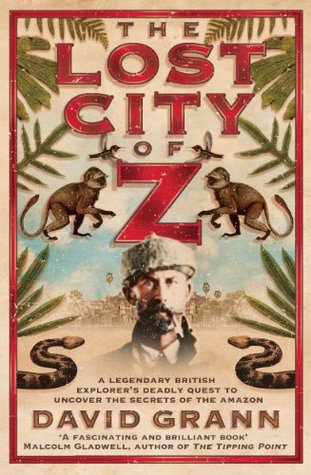

The Lost City of Z: A Legendary British Explorer's Deadly Quest to Uncover the Secrets of the Amazon

by

David Grann

Read between

April 7 - April 14, 2023

Some four thousand men died during that expedition alone, of starvation and disease and at the hands of Indians defending their territory with arrows dipped in poison. Other El Dorado parties resorted to cannibalism.

most archaeologists had concluded that El Dorado was no more than an illusion.

He was also afraid that if he released details of his route, and others attempted to find Z or rescue him, it would result in countless deaths. An expedition of fourteen hundred armed men had previously vanished in the same region.

For five months, Fawcett had sent dispatches, which were carried through the jungle, crumpled and stained, by Indian runners and, in what seemed like a feat of magic, tapped out on telegraph machines and printed on virtually every continent; in an early example of the all-consuming modern news story, Africans, Asians, Europeans, Australians, and Americans were riveted by the same distant event. The expedition, one newspaper wrote, “captured the imagination of every child who ever dreamed of undiscovered lands.”

Fawcett began to chafe at the confines of Victorian society. He was too much of a loner, too ambitious and headstrong (“audacious to the point of rashness,” as one observer put it), too intellectually curious to fit within the officer corps.

“I wanted to listen to the everyday chit-chat of the village parson, discuss the uncertainties of the weather with the yokels, pick up the daily paper on my breakfast-plate. I wanted, in short, to be just ‘ordinary.’ ” He bathed in warm water with soap and trimmed his beard. He dug in the garden, tucked his children into bed, read by the fire, and shared Christmas with his family—“as though South America had never been.”

This is what always spark my curiosity. Under what cicumstances would you leave behind civilisation and into the unknown?

“He was fever-proof,” said Thomas Charles Bridges, a popular adventure writer at the time who knew Fawcett. The trait caused rampant speculation about his physiology. Bridges attributed this resistance to his having “a pulse below the normal.” One historian observed that Fawcett had “a virtual immunity from tropical disease. Perhaps this last quality was the most exceptional. There were other explorers, although not many, who equaled him in dedication, courage and strength, but in his resistance to disease he was unique.” Even Fawcett began to marvel at what he called the “perfect

...more

One Guarayo crushed a plant with a stone and let its juice spill into a stream, where it formed a milky cloud. “After a few minutes a fish came to the surface, swimming in a circle, mouth gaping, then turned on its back apparently dead,” Costin recalled. “Soon there were a dozen fish floating belly up.” They had been poisoned. A Guarayo boy waded into the water and picked out the fattest ones for eating. The quantity of poison only stunned them and posed no risk to humans when the fish were cooked; equally remarkable, the fish that the boy had left in the water soon returned to life and swam

...more

“Food problems never bothered them,” Fawcett said. “When hungry, one of them would go off into the forest and call for game; and I joined him on one occasion to see how he did it. I could see no signs of an animal in the bush, but the Indian plainly knew better. He set up ear-piercing cries and signed to me to keep still. In a few minutes a small deer came timidly through the bush . . . and the Indian shot it with bow and arrow. I have seen them draw monkeys and birds out of the trees above by means of these peculiar cries.”

“At least forty million people [are] already aware of our objective,” Fawcett wrote his son Brian, reveling in the “tremendous” publicity. There were photographs of the explorers with headlines like “Three Men Face Cannibals in Relic Quest.” One article said, “No Olympic games contender was ever trained down to a finer edge than these three reserved, matter-of-fact Englishmen, whose pathway to a forgotten world is beset by arrows, pestilence and wild beasts.”

On April 20, a crowd gathered to see the party off. At the crack of whips, the caravan jolted forward, Jack and Raleigh as proud as could be. Ahrens accompanied the explorers for about an hour on his own horse. Then, as he told Nina, he watched them march northward “into a world so far completely uncivilised and unknown by people.”

Bakairí Post, where in 1920 the Brazilian government had set up a garrison—“the last point of civilization,” as the settlers referred to it.

The jungle widened the fissures that had been evident since Raleigh’s romance on the boat. Raleigh, overwhelmed by the insects, the heat, and the pain in his foot, lost interest in “the Quest.” He no longer thought about returning as a hero: all he wanted, he muttered, was to open a small business and to settle down with a family. (“The Fawcetts can have all my share of the notoriety and be welcome to it!” he wrote his brother.) When Jack talked of the archaeological importance of Z, Raleigh shrugged and said, “That’s too deep for me.”

“Only the Indians respect the forest,” Paolo said. “The white people cut it all down.”

By 1934, the Brazilian government, overwhelmed by the number of search parties, had issued a decree banning them unless they received special permission; nonetheless, explorers continued to go, with or without permission. Although no reliable statistics exist, one recent estimate put the death toll from these expeditions as high as one hundred.

Brian wrote in his diary, “Was Daddy’s whole conception of ‘Z,’ a spiritual objective, and the manner of reaching it a religious allegory?” Was it possible that three lives had been lost for “an objective that had never existed”? Fawcett himself had scribbled in a letter to a friend, “Those whom the Gods intend to destroy they first make mad!”