More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

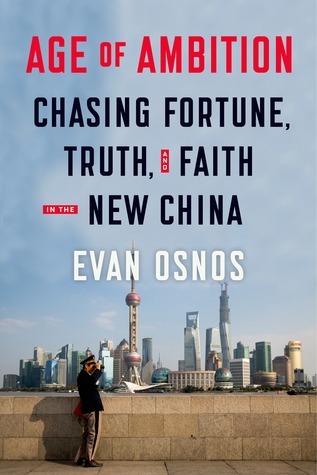

by

Evan Osnos

Read between

December 6, 2019 - January 14, 2020

China’s online life, as in any country, concerned matters less grave. When

Fundamentally, the culture of the Web was an almost perfect opposite of the culture of the Communist Party: Chinese leaders cherished solemnity, conformity, and secrecy; the Web sanctified informality, newness, and, above all, disclosure.

He said the scale of China’s growth obscured the details of how the spoils were being divided.

Chinese young people had been apolitical, not simply because the basic conditions of life had improved but also because the alternative was frightening and hopeless.

The intersection of wealth and authoritarianism posed a predicament for members of China’s new creative class.

“The meetings, you discover, are really boring and useless.

China is holding meetings every day, and even though these meetings are meaningless, China has still developed so fast.

Many Chinese artists, like other elites, have explored Western liberalism or lived abroad, but as with Tang Jie or the Stanford engineer I met in Palo Alto, the exposure heightened their patriotism and made them suspicious of Western critiques of China.

China today and China during the Cold War are worlds apart.”

“If you protest and fail to publish anything about it, you might as well have protested inside your own house.”

local agency that dealt with political dissidents—the General Affairs Office of the Beijing Public Security Bureau—was, like the Central Propaganda Department, a building that did not exist.

Chinese leaders’ performance on the economy looked skillful compared with that of many Western leaders.

censorship, once an abstract and invisible process confined to secret directives and newsroom discussions, was now plainly visible.

most critical reactions came from other expatriates in China. I understood that: foreigners with no reason to probe could spend years in China without ever interviewing someone who had been tortured or locked up without trial, and to them, my focus was misplaced.

Popularity always struck me as an odd way to measure the importance of an idea in a country that censored ideas.

ignoring the impact of a small group of impassioned people struck me as a misreading of Chinese history, in which small groups had often exerted large forces.

It became fashionable to whisper that Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaobo were messianic.