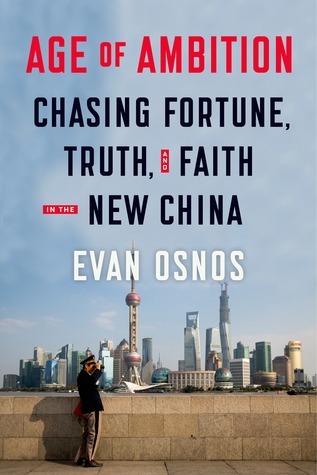

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Evan Osnos

Read between

November 6 - November 21, 2022

Every six hours, the People’s Republic was exporting as much as it did in the calendar year 1978,

China was building the square-foot equivalent of Rome every two weeks. (In 2012 the country became, for the first time, more urban than rural.)

“I don’t believe anyone who truly loves literature can also love Mao Zedong,” he told me. “These two things are incompatible. Even putting aside his political performance, or how many bad things he did, or how many people starved to death because of him, or how many people he killed, there is one thing for sure: Mao Zedong was the enemy of writers.”

Ai Weiwei reveled in confrontation. Now that he was being followed by plainclothes state security agents, he started calling the cops on them, setting off a Marx Brothers muddle of overlapping police agencies: “an absurdist novel gone bad,” as he put it. He inverted the usual logic of art and politics: instead of enlisting art in the service of his protest, he enlisted the apparatus of authoritarianism into his art. At

In 1935 the author and translator Lin Yutang observed, “In China, though a man may be arrested for stealing a purse, he is not arrested for stealing the national treasury.”

In a small town in Inner Mongolia, the post of chief planner was sold for $103,000. The municipal party secretary was on the block for $101,000. It followed a certain logic: in weak democracies, people paid their way into office by buying votes; in a state where there were no votes to buy, you paid the people who doled out the jobs. Even the military was riddled with patronage; commanders received a string of payments from a pyramid of loyal officers beneath them. A one-star general could reportedly expect to receive ten million dollars in gifts and business deals; a four-star commander stood

...more

By 2012 the richest seventy members of China’s national legislature had a net worth of almost ninety billion dollars—more than ten times the combined net worth of the entire U.S. Congress.

In the summer of 2012, people noticed that another search word had been blocked. The anniversary of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations had just passed, and people had been discussing it, in code, by calling it “the truth”—zhenxiang. The censors picked up on this, and when people searched Weibo for anything further, they began receiving a warning: “In accordance with relevant laws, regulations, and policies, search results for ‘the truth’ have not been displayed.”

Karl Marx had considered religion an “illusory happiness” incompatible with the struggle for socialism, and the People’s Daily called upon the young to “Smash the Four Olds”—old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas.

Faced with so many options, some people hedged with a bit of spiritual promiscuity: before the school exams each spring, I watched Chinese parents stream past the gates of the Lama Temple to pray for good scores. Then they crossed the street to pray at the Confucius Temple, and some finished the afternoon at a Catholic Church, just in case.