More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

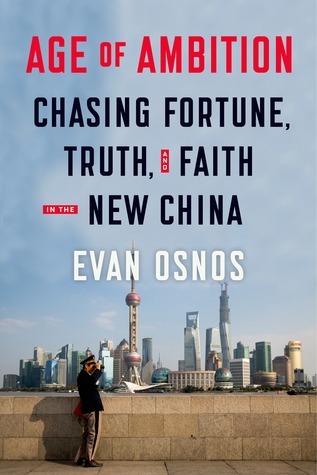

by

Evan Osnos

Read between

February 25 - April 7, 2018

For most of the Chinese people, however, the boom has not produced vast wealth; it has permitted the first halting steps out of poverty.

In 1978, the average Chinese income was $200; by 2014, it was $6,000.

It is the age of the changeling, when the daughter of a farmer can propel herself from the assembly line to the boardroom so fast that she never has time to shed the manners and anxieties of the village.

China reminds me most of America at its own moment of transformation—the period that Mark Twain and Charles Warner named the Gilded Age, when “every man has his dream, his pet scheme.”

This book is an account of the collision of two forces: aspiration and authoritarianism. Forty years ago the Chinese people had virtually no access to fortune, truth, or faith—three things denied them by politics and poverty. They had no chance to build a business or indulge their desires, no power to challenge propaganda and censorship, no way to find moral inspiration outside the Party. Within a generation, they had gained access to all three—and they want more.

At times, the institutional reflex to exert control was breathtakingly counterproductive. At one point, Chinese programmers were barred from updating a popular software system called Node.js because the version number, 0.6.4, corresponded with June 4, the date of the Tiananmen Square crackdown.