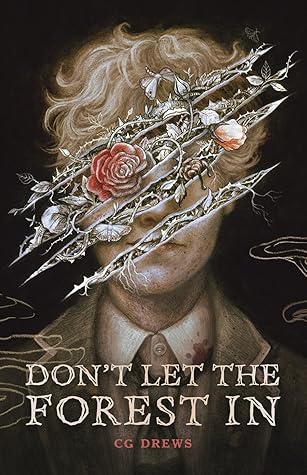

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“You have to give him warning. You know he hates confrontation.” “He could do something for me for once.” Dove sounded tired. “… come on, let’s just go.”

Thomas was so used to no one liking him, no one caring, that when they did, he was always terrified of the day they’d stop.

Andrew picked at the paint crusted on the hem of his shirt. Thomas’s shirt. “There has been an accident.” He wondered what Thomas had been painting since he usually gravitated toward ink and charcoal for his monsters.

His twin had been severed from him, and he hadn’t even been awake to feel it. They asked if he had questions. He didn’t. People kept giving condolences.

They had already accepted the truth of this story they’d made up, this dark and treacherous fairy tale worse than anything he’d ever written.

They took her away. They didn’t even ask him if they could.

Thomas sat at the table staring at a cooling mug before him. When he looked up, his expression was so raw and terrible that Andrew glanced away. They’d flayed Thomas alive, it was easy to see.

Thomas choked on a sob. “I’m sorry—” Andrew hit the mirror.

He no longer looked like Dove, now he was a red-smeared thing in fractured pieces. He hit it again.

He would stop when he’d obliterated every last piece of glass into stardust that he could coat his tongue with and whisper a magic wish to the forest. Give her back.

“I said.” Andrew placed each word like a rusted blade against Thomas’s tremulous throat. “Stop. Talking.”

Dove would absolutely freak out when she saw what he’d done to his hand. He’d explain it to her over breakfast, how it had been a tough, stressful year, and he’d spaced out for a minute. He’d thought there was a monster in the mirror and he only meant to kill it.

“Lana told me that she didn’t think you knew, like somehow you’d … blocked it or something. But I don’t understand. You have to know. You … have to. I tried not to bring Dove up since you didn’t, and I didn’t want to hurt you.”

“I feel so fucking guilty. I should have been with her, and I’m scared you still … blame me.”

“I already told you.” Every word shook as Thomas fought against tears. “I think someday you’ll hate me.”

She didn’t want us to change, us three. It had to be us three, she said, but I never would have cut her out. I just wanted to kiss you. I still”—

cracking—“I still just want to kiss you all the time. We started arguing before we even got to the forest because she said ‘I forbid it’ and I-I flipped out and said you didn’t belong to her.”

“Then she fell. And I wasn’t there to catch her. I didn’t even feel it. I should have felt it or been there or run to her.

But I love you … like you’re my whole world.”

“But how shitty would I be,” Thomas said, raw, “to kiss you after she was gone? This is why Lana hates me so much. She thinks I saw Dove’s … she thinks I saw it as an opportunity to get with you, but I didn’t. I’d rather die than be like that. I just don’t want to be alone anymore. I just—I’m so scared of being alone.”

Andrew, who hadn’t fallen asleep when the dream ravager came. Andrew, who told a wicked fairy tale about a wolf that ate Thomas’s parents. Andrew, who had never stopped writing, even though Thomas had stopped drawing.

Here was a boy who made monsters, or perhaps was a monster himself. All because he couldn’t face the fact, the guilt, the sorrow, the rage, of his sister being dead.

“S-stop.” He practically screamed it. “It’s not him. It’s me. You want me!” “Andrew, shut the fuck up.”

“I’m the tithe,” Andrew said, and his mouth was full of ink.

Thomas screamed at the same moment the forest dug fingers into Andrew’s face and pulled.

He was screaming; he couldn’t stop. Pain bloomed, vicious and bloody and red. With trembling fingertips, he touched his eyelid just as thorny roses unfurled petals dripping with the viscid jelly of his perforated eye. They grew. Blossomed.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that the forest had outgrown the confines of his thin, frail body and longed to stretch. He used to be an empty boy, impossible to fill. Now he was so full of monsters.

Every good story ends with a wishbone snapped, a bloodied kiss, the prince’s sacrifice.

Someone had to finish telling the story.

The whole night made sense, in a brittle, circular way. He took in a lungful of air and felt it slide wet and tar-slick down his throat, a strange sort of calm folding over him.

After this, everything strange and uncanny about the school would stop.

“She wanted everything to stay the same,” Andrew said. “And it couldn’t. It didn’t. We let our love for each other cut us to the bloody core.”

“You didn’t bring a pen.” It took everything in him not to stand there, not to cry. “I’m not telling that kind of story this time. Now take off her face.”

As expected, the place where the Wildwood tree used to be was empty. It had yanked its roots free and gone walking, had packed its body down to look like a girl with honey-blond hair and a name of softened feathers.

The way it looked at him wasn’t cruel or vindictive, rather gentle, as if it realized he had run as far as he could and his tiredness was to be expected.

Once a prince took a knife to his chest and carved himself open, showing ribs like mossy tree roots, his heart a bruised and wretched thing beneath. No one would want a heart like his. But he’d still cut it out and given it away.

He gave his heart to the October boy with one thousand and one freckles and hair of autumn leaves. But almost at once, the heart began to corrode, and the prince turned into a monster. They should bury it, the prince decided, and see what it would grow into.

They decided to bury the heart deep in the woods, for monsters were ravenous things, not to be trusted. This way the October boy would be safe.

Within the ground, the heart grew into a tree and the monster lived among the branches and forgot he had ever been a prince. But the October boy didn’t flee. He climbed the tree and kissed the lonesome monster until it devoured him whole.

To cut out his heart was actually such a small thing.

“Everything stops,” he whispered, “after this.”

“Cut out a heart and bury it in the woods.” Andrew didn’t realize he’d said it out loud until Thomas looked up at him with swollen, glossy eyes and said, “Does it have to be your heart?”

“If you cut open my chest”—Andrew’s voice was wrecked—“you’ll find a garden of rot where my heart should be.”

“I don’t care how dark the world is for you. I’ll hold out my hand until you find it, and I won’t let go.”

“But just know this,” Thomas said as he fought back tears. “Dove’s death was an accident and she never would have haunted you in revenge.

You’re strong enough. You’re brave enough.”

They didn’t need two hearts. They could share Andrew’s, even if it was a bruised and sorrowful thing. Their rib bones would twine together in a lattice to protect them from the worst of the world and they would always be together; they should never be apart.

the Wildwood tree looked like an old white oak again with branches stretched in a wide, leafy arch, thick whorls and knots in the bark at the perfect height for handholds if one dared to climb. One branch was broken.

The way Andrew loved Thomas was terrible and eternal, but he couldn’t remember if he’d ever said that out loud.

“Remember you love me.” His words felt so small and sleepy against the forest’s dawn. “All my stories are about you. They will always be about you.”