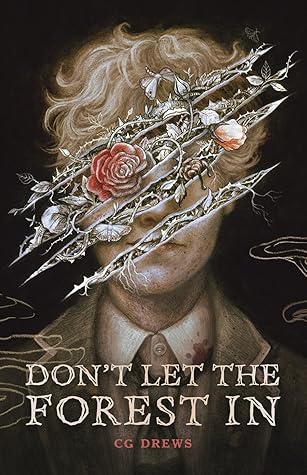

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Other people existed only in Thomas’s periphery, but the Perrault twins eclipsed his entire galaxy. There was something intoxicating about meaning that much to one person.

Other people existed only in Thomas’s periphery, but the Perrault twins eclipsed his entire galaxy. There was something intoxicating about meaning that much to one person.

Except one look at Thomas and anyone could see his mouth was crammed full of thorns and lies.

Except one look at Thomas and anyone could see his mouth was crammed full of thorns and lies.

Thomas went off on a rant about how math was offensive, or how he belonged to the forest like some sort of fae child who planned to run away to the trees and never look back.

Thomas went off on a rant about how math was offensive, or how he belonged to the forest like some sort of fae child who planned to run away to the trees and never look back.

Thomas, who breathed best with his cheek pressed against a tree and never wasted a chance to slip out and be as wild as his soul demanded.

Thomas always drew like this—murderous and dark, sentient forests with teeth and claws, boys made of thorns, studies of hands with flowers blossoming from cuts. Beautiful and horrible all at once. He drew like this because Andrew wrote like this. They fed off each other relentlessly, their fever dreams bleeding through their eyes long after they woke.

Their story had begun in the forest, a collision both violent and beautiful.

Andrew was a glass figurine. Drop him and he shattered.

But there was one boy who obviously loved the forest more than Andrew, a freckled kid with a reckless mouth and hair kissed by the devil.

“I can handle you,” Andrew said. He’d meant to say I can handle it. A smile broke across Thomas’s face, all sharp edges and cleverness. Andrew loved it.

An extraordinary amount of intimacy lay in exchanging art. Not for critique and not for class. Just to look. To feel. To understand each other.

think someday you’ll hate me.” Thomas’s voice stretched with a loneliness Andrew had never heard before. “You’ll cut me open and find a garden of rot where my heart should be.”

“When I cut you open,” Andrew finally said, “all I’ll find is that we match.”

To write something nice, he’d need something nice to say. But his ribs were a cage for monsters and they cut their teeth on his bones.

What were twins, if not one to shout and one to whisper?

He didn’t fit with those kids because he didn’t fit with anyone except Thomas and Dove, and he didn’t know if he was gay enough when there was only one boy he wanted.

As if that would stop Thomas. The forest was immense and unmappable and monstrous—and it had always belonged to him.

Then the underbrush thinned and his destination sprawled before him—a white oak big enough to hold up half the sky. It was ancient and lovely, with branches that curled like hands reaching out to welcome him. They called it the Wildwood tree and had been climbing it since they were kids. They used to whisper their fears into the bark so it could swallow their words whole.

possible.” It hit like a punch. This wasn’t happening. This didn’t happen. They didn’t fight. Make it stop. It had to stop.

Andrew needed it and hated that he did. It never stopped making him feel small, the way Thomas had to nurse his anxiety. It lived between them, this knowledge that Andrew couldn’t cope and so Thomas took care of it. Right up until he didn’t want to anymore.

“Anyone could be a monster. In the right circumstances. Motivated by the right thing. To protect someone else or to … to protect yourself. Is it that wrong to fight for yourself if no one else will?”

He shook so hard with fear that he forgot to struggle. Don’t scream. He had to keep his mouth closed. Don’t let it in.

His chest had been caved in from battles fought and lost, and they’d filled the space between his ribs with flowers. Even now the flowers grew, blossoming as they drank the last of his blood.

Behind the princess stood her brother, a poet with soft lips and soft moss for hair. He whispered, “Let me try.” But no one heard.

He was so relieved that a manic smile tugged at his lips. Sure, monsters were real and wanted to rip out their throats, but at least he still had his best friend.

“They’ll kill you like they want to kill me. I can’t bear it if they take you from me, too. I need—I need—I’m so goddamn tired.

For a vicious moment, Andrew thought about slipping his fingers into Thomas’s cut. Taking hold of his rib and breaking it. Pulling the soft crumbling bone from his chest and sewing it into his own. They’d be forever together, rib against rib, fused in gore and bone and adoration.

Andrew sighed. “I think … it’s because everything wrecks me. Everything. I’m so freaked out all the time and there’s no reason, just my brain imploding on itself. But monsters are something we can kill, and I think I like that.” He let out a flat laugh. “My brain is so broken.”

Life didn’t fit against his skin and it never had and sometimes everything was just too much.

Maybe it was easier to whisper sweet and aching things in the dark.

There was something so raw about being known this intimately, being understood down to his darkest parts. Andrew’s heart felt swollen to twice its normal size.

If the trees belonged to Thomas, midnight was in love with Andrew. It made him braver somehow, invisible, hiding his delicate edges and leaving behind a lean and hungry shadow. In the dark, no one could see his hollow and empty places. Instead he looked like he could have teeth.

Andrew felt sick. He’d wanted to get out of eating and so he had. As if he’d asked for it.

there you are prince

What would it even look like, to cut their feelings out, bloody and aching and raw, and compare them? To find they didn’t match. To be left with guts vivisected and no way to sew themselves back up so they looked the same as before.

Andrew loved this boy so deep and whole and obsessively that he couldn’t breathe, and the weight of it terrified him.

The hardest for last. His hair curled in soft honey waves, dandelions woven between the strands. But his mouth was missing. As if Thomas had been waiting to learn the shape of it first.

He was a wretched thing, a rotten thing, a skeleton with his insides already devoured by the forest.

He was so tired of suffering because he moved through the world differently from everyone else. This wasn’t only about goddamn monsters. It was about how he never seemed able to cope, how the world didn’t fit against his skin, how he felt too much and hurt too often and couldn’t pack his emotions into neat, palatable boxes. He needed help. He needed someone to hold on to. He needed to be believed. It didn’t matter if what hurt him was an invisible weight inside his head or something that left real bruises against his skin: His pain was real.

“Sometimes you choose your own reality, Andrew. You’ve always been like this, and I’m not angry at you. I understand. It’s like when we were little, you’d tell these sprawling, fantastical stories, but they never ended. Even when I got tired of playing, you wouldn’t. You’d lie on the carpet for hours just playing alone … in your head.” Her voice had gone thin and rusted, and she fought to steady herself. “Thomas made you interested in this world. And I get it. I’m grateful to him. But…”

“Andrew.” Thomas’s voice cracked. “It can’t be her. You know that.” His eyes looked like a thousand shattered mirrors as he pressed his thumb to Andrew’s mouth. All he could taste was blackberry briars and dirt and forest rot. “That thing was not Dove because Dove is dead.”

loved her like she was my family. But I love you … like you’re my whole world.”

“But how shitty would I be,” Thomas said, raw, “to kiss you after she was gone? This is why Lana hates me so much. She thinks I saw Dove’s … she thinks I saw it as an opportunity to get with you, but I didn’t. I’d rather die than be like that. I just don’t want to be alone anymore. I just—I’m so scared of being alone.”

Here was a boy who made monsters, or perhaps was a monster himself. All because he couldn’t face the fact, the guilt, the sorrow, the rage,

As expected, the place where the Wildwood tree used to be was empty. It had yanked its roots free and gone walking, had packed its body down to look like a girl with honey-blond hair and a name of softened feathers. A distant part of him wondered how much of Dove’s blood it had drunk as she died, quiet and alone under its canopy.

Within the ground, the heart grew into a tree and the monster lived among the branches and forgot he had ever been a prince. But the October boy didn’t flee. He climbed the tree and kissed the lonesome monster until it devoured him whole.

And to you, reader, thank you. May this one haunt you.