More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

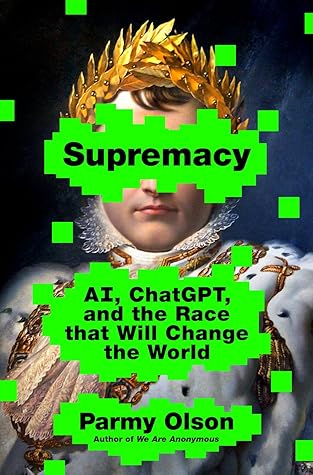

Parmy Olson

Read between

March 23 - March 28, 2025

What’s remarkable is how quickly this has all come to pass. In the fifteen years that I’ve written about the technology industry, I’ve never seen a field move as quickly as artificial intelligence has in just the last two years. The release of ChatGPT in November 2022 sparked a race to create a whole new kind of AI that didn’t just process information but generated it. Back then, AI tools could produce wonky images of dogs. Now they are churning out photorealistic pictures of Donald Trump, whose pores and skin texture look so lifelike they’re almost impossible to distinguish as fake.

But neither company is satisfied. Microsoft wants to grab a chunk of Google’s $150 billion search business, and Google wants Microsoft’s $110 billion cloud business.

AI future has been written by just two men: Sam Altman and Demis Hassabis.

Altman was the reason the world got ChatGPT. Hassabis was the reason we got it so quickly.

“Solve intelligence, and then solve everything else,”

Altman was that one kid in high school who seemed to magically transcend the labels that others tried to slap on him.

student paper. The young man was utterly unintimidated by authority,

would learn over time that people in power could smooth the road for your ambitions,

Altman left school with a hard lesson. If you had ambitious ideas, there would always be some haters. The solution was to align yourself with those who had power and authority and to surround yourself with a support network.

Poker is all about watching others and sometimes misdirecting them about the strength of your hand, and Altman became so good at bluffing and reading his opponents’ subtle cues that he used his winnings to fund most of his living expenses as a college student.

loved it so much. I strongly recommend it as a way to learn about the world and business and psychology.”

Thrun explained that AI systems could act in unpredictable ways to achieve their “fitness function,” or goal. If an AI was designed with a fitness function to survive and reproduce, it might inadvertently wipe out all biological life on Earth, Thrun said. This didn’t mean the AI was bad. It was just unaware of the gravity of what it was doing. Its motives weren’t all that different from ours when we washed our hands. We didn’t hate the bacteria on our skin and want to destroy it. We just wanted clean hands.

most popular essays, the ones that made kids like Altman sit up in the kind of rapt attention given to spiritual leaders, were about building start-ups. Over and over, those essays emphasized that the quality of a start-up founder mattered more than anything else. You didn’t need a brilliant idea to start a successful tech company. You just needed a brilliant person behind the wheel.

Google’s plan, for example, was simply to create a search site that didn’t suck,” Graham wrote. And look where that had led. Lightbulb moments were passé. It was the founders who mattered, and the best were hackers—programmers who were willing to break conventional wisdom to build new things. As a hacker, “you could be 36 times more productive than you’re expected to be in a random corporate job,” he wrote.

The path was almost simple, Graham taught. Bootstrap your company, start with a minimum viable product, and optimize it over time. Work in a tight bubble, because it was better to have ten people love what you made than thousands liking it. And don’t be afraid to bend the rules along the way. In fact, why not rewrite society itself?

same hacker instincts in Altman: deeply curious, fiercely intelligent, and a big thinker. And there was something else. This teenager with unruly dark hair was comfortable around older people to the point that he’d have no trouble managing people like Graham, who was twenty years his senior.

Graham told founders to do more with less, and aim for “ramen profitability,” discouraging them from hiring lawyers, bankers, and PR people so they could do that work more cheaply themselves.

Silicon Valley was the land of crazy thinkers. You didn’t start a business here. You started an empire.

Altman quickly integrated himself into Silicon Valley’s web of programmers, investors, and executives. If you knew how to plug yourself into this modern old-boys network, you were more likely to get swept up in the success that propelled its members to billionaires. Altman was so good at networking that he managed to make the right connections to present Loopt at Apple’s prestigious annual conference for developers in 2008.

In the world of tech start-ups, a founder’s ultimate goal is to either have their idea become a multibillion-dollar company or make a multibillion-dollar exit by selling their firm to a bigger fish. It was becoming harder to stay independent, and most were getting swallowed up by a tech giant like Google or Facebook.

If you throw a smartphone at a group of people sitting inside the exclusive Battery Club in San Francisco, it’ll hit at least three trying to save the world.

Hassabis drew inspiration from god games, and his favorite was Populous. “What fascinated me about them was that they were living worlds, and the game evolved with how you played it,” he says. “You could simulate a part of the world as a sandbox and you could play around it.”

he was going to build games that not only had superior capabilities but would drag gaming itself out of its niche market for teens. He would build something so clever that readers of The Economist would want to play it. “I wanted to show games could be a serious medium, like books and film,” Hassabis says. He sketched out a long-term plan. Once Elixir was successful, he’d sell it and start an AI company. He focused on building a flagship game called Republic: The Revolution, a political simulation where players had to overthrow the government of a fictional, totalitarian country in eastern

...more

“The essence of a video game is immersion and feeling,”

It was OK to be frequently wrong, he believed, so long as you were occasionally “right in a big way,”

“we learn only two bits a second.” A bit is a basic unit of information, typically represented as a 0 or a 1 in binary code, and this was Altman’s figurative way of showing how limited humans were in processing information. If you compared the mechanics of our brains to how computers worked, computers could process bits at a much more impressive rate: in gigabits or terabits per second.

“There is a relentless belief in the future here,” he once said. “There are people here who will take your wild ideas seriously instead of mocking you.” Silicon Valley also promised a thriving network of contacts who would scratch your back if you scratched theirs. Help someone fundraise for their start-up, and they might help you hire that talented engineer.

If you’re wondering where Altman got the money for that, remember that he put about $3 million into Cruise well before that start-up sold to General Motors for $1.25 billion, earning him a windfall. His place at the top of YC meant he was better positioned than many other venture capitalists to win jackpots like that, getting an intimate view on hundreds of companies who’d already been carefully screened, and in the middle of one of the greatest bull market runs in history. Getting pitched by all those start-ups also helped him see into the future.

“You have to have an almost crazy level of dedication to your company to succeed,”

take whatever number measured success and “add a zero.” To fix a broken world, founders had to be obsessive about product quality, “relentlessly resourceful,” and able to “overcommunicate” with their team. There was no such thing as work-life balance in this world.

Silicon Valley was where people came to build empires, and you didn’t build an empire by working forty hours a week. But his real gift as an entrepreneur was his power to persuade others of his authority. He had drawn the admiration of mentors, from his high school principal to Y Combinator’s Graham and Livingston to Peter Thiel, along with thousands of start-up founders. But Altman also had an underlying dissonance: a brilliant mind driven to protect the world that was also emotionally distant from the regular people he sought to save.

“One thing I realized through meditation is that there is no self that I can identify with in any way at all,”

“The Gentle Seduction” by the American science fiction author Marc Stiegler, about the future impact of tech on people’s lives. The story follows the life of Lisa, a woman who encounters various advancements that “seduce” her into incorporating tech into her daily life. Toward the end, Lisa and her husband are undergoing the process of uploading their consciousnesses into a computer. It’s a risky procedure and the people who merge their minds with this advanced machinery can end up losing themselves, so Lisa weighs the pros and cons, noting that some of her friends who tried it ended up

...more

Altman was struck by that quote and would repeat it to others. The author was saying that to survive the risks of merging with computers, people needed to adopt a mindset that balanced caution and bravery. You were more likely to survive a future threat by being careful and cool-headed, rationally assessing dangers, instead of reacting emotionally and succumbing to panic. The people who thrived in the future would take a detached and informed approach to tech advancements.

took inspiration from Alan Turing, the twentieth-century British computer scientist who came up with the Turing machine. Introduced in 1936, it was essentially a thought experiment, a “machine” that only ever existed in Turing’s mind. He envisioned a length of infinite tape that was divided into cells, as well as a tape head that could read and write symbols on the tape, guided by certain rules, until it was told to stop. The idea sounds rudimentary, but as a theory, it was critical in formalizing the concept that computers could use algorithms—or sets of rules—to do things. Given enough time

...more

“The human brain is a Turing machine,”

Till then, it was thought that the brain’s hippocampus

mostly processed memories, but Hassabis showed (with the help of other studies of MRI scans in his thesis) that it was also activated during the act of imagination. In simple terms, this meant that when we had a memory, we were partly imagining it. Our brains weren’t just “replaying” past events by retrieving them, as you might take a file out of a filing cabinet, but actively reconstructing them in the way you might paint a picture. The brain was engaged in a much more dynamic and creative process, which went some way to explain why our memories sometimes were plain wrong and could be

...more

Suleyman was eager for Hassabis to read a book that had shaped his view of the world. Called The Ingenuity Gap, it was published in 2000 by Canadian academic Thomas Homer-Dixon and argued that the utter complexity of modern-day problems, from climate change to political instability, was outpacing our ability to come up with solutions. The result was an ingenuity gap, and humans needed to innovate in areas like technology if they wanted to close it. That’s where AI could fit in, Suleyman figured. Hassabis shook his head. “You’re missing the bigger picture,” he once told him, according to

...more

Hassabis summed up that view in DeepMind’s tagline: “Solve intelligence and use it to solve everything else.” He put it on their slide deck for investors.

“Solve intelligence and use it to make the world a better place.”

Hassabis is coy when asked if he believes in God. “I do feel there’s mystery in the universe,” he says. “I wouldn’t say it’s like traditional God.” He says that Albert Einstein believed in “the God of Spinoza, and maybe I’d give a similar sort of answer.” Baruch Spinoza was a seventeenth-century philosopher who proposed that God was effectively nature and everything that existed, rather than a separate being. It was a pantheistic view. “Spinoza thinks of nature as the embodiment of whatever God is,” Hassabis says. “So doing science is exploring that mystery.”

And if AGI research led to the conclusion that our universe was a simulation—as Kurzweil himself has proposed—the original programmer could well be a godlike entity. Similarly, if humans created a powerful machine that ingested and analyzed all available information about physics and the universe, that machine could also propose new theories that suggested the existence of a higher power. It might just answer deep existential questions that pointed to a divine entity. There were myriad ways that with greater capabilities and intelligence, AI could unlock one of humanity’s most profound

...more

A 2023 study from the University of Virginia that involved more than fifty thousand participants from twenty-one countries found that people who believed in God or thought about God more than others were more likely to trust advice from an AI system like ChatGPT. According to the researchers, these people were more receptive to AI guidance because they tended to have greater feelings of humility. They were also quick to recognize human flaws.

In the UK, tech start-ups tended to chase “sensible” business ideas that would make money more quickly, like building a financial app for trading stocks and bonds. Hassabis and his cofounders had little choice but to look to Silicon Valley, where investors were willing to bet bigger amounts of money for more futuristic ideas.

Thiel was so contrarian that he was often at odds with the rest of Silicon Valley, which was already full of unconventional thinkers.

While most entrepreneurs believed competition drove innovation, Thiel argued in his book Zero to One that monopolies did that better. He scorned the conventional routes to success, encouraging smart, entrepreneurial kids to drop out of college and join his Thiel Fellowship. And his wacky pursuits for longevity and the singularity meant he fit the “crazy” criteria the DeepMind founders were after.

“I think one reason why chess has survived so successfully over generations is because the knight and bishop are perfectly balanced,” Hassabis told Thiel as canapés were being passed around. “I think that causes all the creative asymmetric tension.”

“I’m Jaan. I’m the [cofounder] of Skype.” Originally from Estonia, Jaan Tallinn was a computer programmer who developed the peer-to-peer technology underpinning Kazaa, one of the first file-sharing services used to pirate music and movies in the early 2000s. He repurposed that technology for Skype and took a stake in the free calling service before getting a massive windfall when eBay bought Skype for $2.5 billion in 2005. Now he was sprinkling some of his winnings into other start-ups. When Tallinn heard Hassabis speak, his ears pricked up. He’d recently become passionate about the dangers of

...more

He believed that AI was more likely than anyone realized to annihilate humanity. Once it got to a certain level of intelligence, for instance, AI could strategically hide its capabilities until it was too late for humans to control its actions. It could then manipulate financial markets, take control of communications networks, or disable critical infrastructure like electrical grids. The people who were building AI often had no idea that they were bringing the world closer and closer to its destruction, Yudkowsky wrote.