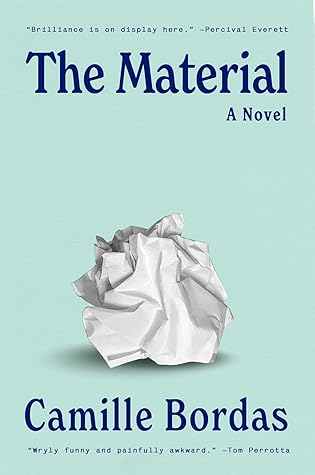

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

He was okay with that, in principle: words taking on larger meanings, larger responsibilities over time—language was a living entity, it adapted to its speakers.

“You have a new memory.” What did that even mean? That he hadn’t had it before? Also, the screen wasn’t showing him a memory, only a stupid selfie. More of that imprecision, he thought, more of that turning words into more or less than they actually were—manicures into “self-care,” meat into “protein.” A photo wasn’t a memory. A photo was a photo. The memories Artie had of that day weren’t at that angle, the light was different. They might end up reduced to that angle and that light, though, if he looked at the photo long enough.

It didn’t really matter anyway. The world was too full, he thought, and nothing you said would ever be considered original thinking, even when it felt pretty original to you.

Artie sometimes believed that his brother’s hope in disappearing repeatedly was for his disappearances to become so routine he’d reach a point where people would stop wondering where he was, or noticing he was gone at all.

Olivia said that it was easier for a man to be funny and moving at the same time, because all a man had to do to move an audience was let it know that he was not entirely oblivious to his surroundings, and sometimes even capable of emotion, and that was enough to break people’s hearts.

“Whereas women,” she went on, “you expect them to be full of doubts and feelings. You expect them to notice how sad everything is all the time. So it doesn’t have the same impact when they let you see their humanity. It’s never poignant. It’s almost just annoying.”

Before, there had always been a buffer between any suicidal thought Olivia had had and the idea that she could act upon it—the two had never quite aligned and faced each other. If she thought, I want to die, something within her immediately shrugged its shoulders and said, Tough shit. Or, depending on its energy level, just hung there all sorry and dumb, like a bad salesman. That “something within her” was her sadness, Olivia thought, its own character in her life. An annoying presence, but also comforting, like a mother, not anything that would ever want to cause her harm. Or so she believed,

...more

It wasn’t as simple as “I felt all this fear for nothing,” but that was definitely part of it. The idea that everything in her life had the potential to become material had always soothed as much as exasperated her. She was never able to tell whether she was living something or already writing it.

This was how the inside of her head was at all times: layers upon layers of self-hatred, mixed in with a lot of pride, ideas for bits, and attempts to solve whatever else was going on that day. She was always working on three or four issues simultaneously.

It was always the same kind of people who annoyed her: people who seemed comfortable, people who seemed to have found their spot in the world and to think that they deserved a medal for it, people who thought themselves better than those who were still looking, or had given up on ever finding.

it was stronger to repress it all and let it rot somewhere in your brain than to bring it back to life over and over again, that being alive meant pushing things down deeper and deeper all the time, to make room for new stuff, and that she’d been good at doing this,

How could you tell something was finished? When you worked on a bit, it quickly ceased being funny to you. You had to operate on faith, on a vague memory that the stuff had excited you at some point and was worth pursuing. Tightening a bit could feel right, sharpening it could make you feel smarter, but after a while, what you couldn’t count on was knowing whether it was funny at all. You had to rely on others for that.

He pretended that people liking his stuff was the right metric, but people had shit taste, everyone knew that, and the truth was, he was haunted by what haunted all artists, the question of whether or not he would respond to his own work, laugh at his own jokes if he were hearing a stranger make them for the first time.

Some parents wanted their children to be confident, happy, or maybe just satisfied with what they had, but Louis’s goal had always been for his son to be humbled by the world. To know his place.

It wasn’t fair. On good days, Kruger thought: Who cares? Who past the age of seven still expected the world to be fair? But on others, he felt single-handedly responsible for the rise of the false equation between success and talent. It wasn’t as dangerous as the one between success and influence, but it was pretty embarrassing still.

Everyone was going to have some terrible thing happen to them at some point in life. Everyone, in the end, if you measured their worth against the amount that they’d suffered, could be absolved. Or partly absolved.

He liked seeing people’s minds go elsewhere. He never felt threatened by it, or insulted. If anything, it was people who paid his presence and what he said too much attention that he found dubious.

He felt propelled down to a secret hole in the ground. Rather, he felt his body stay on the surface of the earth, for show, but his stomach and brain drop many feet below to a secret underground that had been there all along, a secret underground