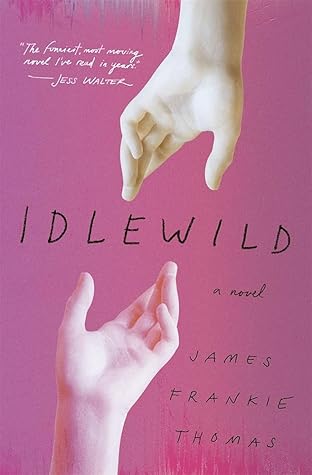

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

She had the kind of hair that I’ve now come to associate with teenage proto-butches: long, almost down to her waist, a length that suggested not vanity but accidental neglect.

Iago is gay like a black leather whip, like Paris in the 1920s, like calling non-food things delicious. Iago is gay like cold eyes and bony hips, like a pearl-handled pistol tucked in one’s suit pocket, like delicate fingers that could play a Chopin prelude or crush a

throat with equal grace. Iago is gay in the way that we the F&N unit aspire to be gay, but it’s harder for girls.

As a teenager, I preferred this explanation. There was something comforting in the idea that my real sexuality existed elsewhere, somewhere so remote and well protected that it was inaccessible even to me.

The image set my heart racing with joyful narcissism, a full-body epiphany that this was it—with “it” existing simultaneously as “the physical manifestation of what I like best about myself” and “that which I most wish to fuck.”

(I never thanked Nell for anything. There would come a time, later, when I wanted to, but by then the backlog was too vast; I didn’t know where to begin.)

Up till then I had never been forced to confront my own inability—an inability so total it bordered on the neurological—to picture myself as an adult. I couldn’t fathom being anything other than what I currently was. I couldn’t be what I currently was anywhere other than at Idlewild.

Theo leans forward, interested. “So you think evil characters are gay?” F: [really getting into it now] “Well, good and evil are heterosexual concepts.” N: “It’s more about being, like, chaotic.” F: “Trickster gods.”

I was a person whose life was ruled by the fear of making someone mad.

Honestly, I don’t even know exactly why. Juniper was annoying, for sure, but Fay and I were annoying too. I think I just got swept up in the fun of having an enemy. So I’m sure my seventeen-year-old self would say something like, “Juniper Green deserves nothing.”

Often at such times, my sense of existing on the outside of my own life—on the outside of humanity, even—caused me distress. Now, when I consider it as a lifelong pattern, it disturbs me.

He regarded me unblinkingly. “You’re not a girl,” he said. “You’re like this weird sad pervy gay guy in a girl’s body, cruising me.” 4. Identification in the wild: He saw me. He understood me. He knew me.

Had Nell been at my side, I would have yelled at him—she and I would have yelled at him in unison and laughed about it afterward. How powerful we were together, Nell and I. How useless I was without her.

Maybe, I thought, this was just how it felt to have a cool gay friend group. Maybe it was always this exhausting and destabilizing. Maybe, in that sense, it was like being in love.

“I’ve never, like, suffered for being a lesbian, you know? Idlewild is such a boringly tolerant place.”

“There are gay kids out there whose parents beat them, or kick them out, or send them to But I’m a Cheerleader camp to make them ex-gay.” “At least those parents are being honest, though,” said Christopher. “Instead of acting all supportive but then being homophobic behind your back.”

None of this was real, he reminded himself ferociously. Life was a dollhouse and Christopher was just a doll he could play with. A beautiful doll that belonged to him.

Something huge was blooming inside me, or maybe something huge was blooming in the world and I was just lucky enough to witness it. Gay kissing, right here at Idlewild! I’d thought it was impossible—I don’t think I’d ever fully realized, until that moment, just how impossible it had always felt to me—and now, boom, it was happening. What else was possible now? Anything. Everything. The world had cracked wide open and you could kiss your best friend and you would still be yourselves, the music would keep playing, the show would go on.

My happiness was too big to be mine alone—it must be coming from her, glowing off her like light. I let it fill me up, felt myself go shiny and rainbow-sparkly. I was part of that spinning disco ball again.

All adult eyes turned to me. There seemed little point in trying to convey to them what was at stake for me—that no place existed where I could make myself understood as I was understood at Idlewild. When I left Idlewild, I would cease to exist.

I screamed and automatically began to thrash, fishlike, in his grip. His hands clenched into my shoulders, as if to flip me over. He was stronger than I—the thought registered dully in the back of my mind—because he was growing into a man, and I was not, and in the end there was no way around that.

What I felt in that taxi was not precisely self-loathing, but grim self-knowledge. I knew myself to be an impostor in Nell’s world. I knew that I had tried and failed to attach myself to her queerness—which existed independently of me, even as mine was contingent on hers—and that I’d hurt her in the attempt. And I knew, even then, that I would spend the rest of my life trying to outrun the shame of it. An escape route was already forming in my mind.

But as I already knew, Idlewild wasn’t the kind of school where kids got bullied for being openly gay. Idlewild was the kind of school where theoretically it was okay for kids to be openly gay, but no one was dumb enough to test this in practice except me, and now I would never be known or remembered as anything but Nell the Lesbian. But that had always been true, hadn’t it? It just hadn’t mattered, not with Fay by my side. That was why I’d loved her: I was so excited to be gay, and she was the only one who really got that. What a stupid irony that she also ended up being the one to make me

...more

I loved her as I loved myself—uneasily, protectively, sometimes not at all—but perhaps I didn’t know her.

Here’s the thing: I’ve never forgotten how it felt to love Fay. For a year and a half, my brain merged into hers until I had no idea where she ended and I began. I know if I tried to explain that to anyone, it would sound scary. Like I lost myself to her. At the time, though, it felt like just the opposite. I knew exactly who I was. I was Fay’s best friend. We loved theater and gay shit and ourselves. We went to Idlewild. I regret who I was back then. At the same time, I don’t know if I’ll ever be happy in the same way again. And I don’t know what to do with that.

“The friendship is what’s making me turn the pages.”