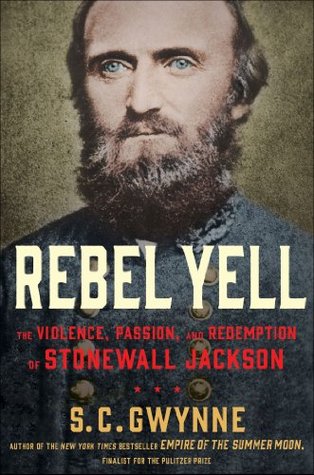

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

S.C. Gwynne

Read between

November 21 - December 5, 2024

a mere fourteen months earlier, the man everyone from Charlottesville to Washington was so breathlessly concerned about had been an obscure, eccentric, and unpopular college professor in a small town in rural Virginia. He had odd habits, a strangely silent manner, a host of health problems, and was thought by almost everyone who knew him to be lacking in even the most basic skills of leadership. To call him a failure is probably too harsh. He just wasn’t very good at anything; he was part of that great undifferentiated mass of second-rate humanity who weren’t going anywhere in life.

Jackson’s rise to fame, power, and legend was every bit as deep and transfiguring as that of the two Union generals. But it happened much faster, and his ascent was much steeper.

In a war where the techniques of marching and fighting were being reinvented almost literally hour by hour, Jackson’s intelligence, speed, aggression, and pure arrogance were the wonders of North and South alike. They were the talk of salons in London and Paris.

He was such a literalist when it came to duty that he had once, while in the army, worn heavy winter underwear into summer because he had received no specific order to change it.

had done everything in his power to prevent the war that he was now marching off to fight. He hated the very idea of it. His conviction was in part due to his peculiar ability, shared by few people who landed in power on either side—Union generals Winfield Scott and William Tecumseh Sherman come prominently to mind—to grasp early on just how terrible the suffering caused by the war would be, and just how long it was likely to last.

Jackson’s brilliance was that he understood war. He understood it at some primary, visceral level that escaped almost everyone else. He understood it even before it happened.

By that he meant making war so brutally expensive for both sides that they would quickly sue for peace. He meant instant, total war. Amid Jackson’s ardent peace prayers, these harder-edged, less charitable thoughts dwelt also.

In the end, he chose war because he believed Virginia had no choice and, like most people in the United States of America in the year 1861, Jackson’s first loyalty was to his home state.

He was motivated by the belief that, for the South to win against obvious industrial and numerical odds, it would have to win quickly. That meant hitting the enemy’s green troops hard and soon, and not paying attention to such political niceties as state boundaries. That meant burning Baltimore and Philadelphia and making Northerners understand on a visceral level what this war was going to cost them. As early as the week after secession, Jackson had proposed to Virginia governor John Letcher the idea he had mentioned in the letter to his nephew in January: a war of invasion in which the South

...more

They also discovered the first of war’s horrors, the sort that affected both armies equally and would eventually claim two soldiers’ lives for every one lost on the battlefield: disease. Epidemics of mumps, measles, and smallpox swept through the valley army in the late spring and early summer, adding to the misery already caused by the inevitable, intractable camp illnesses: diarrhea, dysentery, malaria, and typhoid.

The central—and somewhat bizarre—characteristic of the war was that the capital cities of the two enormous nations—the Confederacy alone encompassed 750,000 square miles and 3,000 miles of coastline—were just 90 miles away from each other.

Winfield Scott, was in most ways larger than life. Scott was the nation’s preeminent soldier. He was, as it happened, actually older than the United States itself. Virginia-born in 1786, he had been a hero as a young man in the War of 1812, became general in chief of the US Army in 1841, and was the chief architect of its stunning victory in the war with Mexico. He ran as the Whig Party candidate, and lost, in the presidential election of 1852. He was everyone’s idea of what a general ought to look like. A massive six feet five inches tall, with splendid side-whiskers and hair swept back from

...more

He would not say that he wished that any circumstance was different than it was, meaning he could not bring himself to wish that it were warmer, or less windy, or even that some accident had not happened. If someone said, “Don’t you wish it might stop raining?,” he would reply with a quiet smile, “Yes, if the Maker of the weather thinks it best,”9 thus instantly killing the conversation.

George B. McClellan, the general who, possessed of an enormous, gleaming weapon, mysteriously refused to use it. He was one of the most remarkable public figures the United States of America has ever produced. The list of his personal attributes was as striking then as it is now. He was an extremely efficient and even gifted administrator. He was good at the business side of running an army. He was also egocentric to a nearly unimaginable degree, harshly judgmental of others, vainglorious, mean-spirited, dissembling, almost pathologically risk-averse, haughty, insincere, back-stabbing,

...more

Jackson might have helped his cause with men and officers if he had given them even the most rudimentary idea of what they were doing, or where they were going. He had told no one anything of his plans, not even his second in command.

Just how far could you push both officers and common soldiers in pursuit of military goals? What the Confederates had done was no ordinary march. Jackson had forced his men to walk more than one hundred miles through a succession of brutal winter storms, high winds, ice, mud, and temperatures that stayed well below freezing. In spite of repeated protests from his officers, conditions that worsened as they marched, and troops with frozen, bleeding, bare feet, he held fast to his objective.

Ninety-four percent of all men killed and wounded in the war were hit by bullets. Jackson’s love of the bayonet was an anachronism: less than half of 1 percent of wounds were inflicted by saber or bayonet.

War, in Stonewall Jackson’s army, was never going to be anything but a hard and desperate thing. There was no stasis, no easy living, no resting on laurels—no rest at all, in fact. Oddly, his footsore army, amid its cursing and grumbling, was starting to embrace this idea. If Jackson was not exactly likable, he was certainly a man you could follow, and in spite of his delphic refusal to share information, he was at least predictable: you were going to march fast and far and then you were going to fight, and you were lucky if you got lunch.

In the next three weeks the valley army suffered from what amounted to mass desertion and mass straggling—often it was hard to tell the difference between the two—much of it the direct result of the extreme hardship of Jackson’s marches. Though the new recruits were most susceptible to this, forced marches with scant rations and minimal equipment in brutal weather conditions affected the veterans, too.

In the fourteenth month of the Civil War, its two most celebrated generals, east or west, were George McClellan and Stonewall Jackson.

Jackson did take care to limit access to two precious commodities: he placed all medicines and medical supplies under guard, and he ordered a large cache of whiskey dumped on the ground. “Don’t spare a drop, nor let any man taste it under any circumstances,” Jackson ordered one of his captains. “I fear that liquor more than General Pope’s army.”

It took McClellan eight days to cross the Potomac and penetrate a mere twenty miles into Virginia, a task Jackson could have accomplished in a day with a barefoot army on half rations.