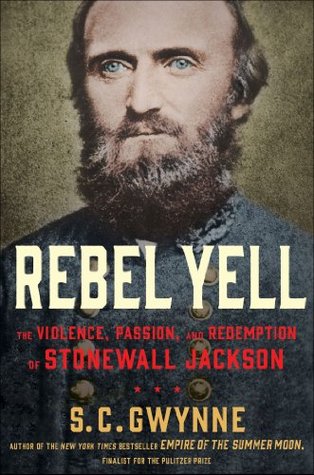

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

S.C. Gwynne

Read between

October 8 - October 26, 2018

For Thomas J. Jackson the war started precisely at 12:30 p.m. on the afternoon of April 21, 1861, in the small Shenandoah Valley town of Lexington, Virginia.

As one Confederate soldier recalled, those days were “the only time we can remember when citizens walked along the lines offering their pocketbooks to men whom they did not know; that fair women bestowed their floral offerings and kisses ungrudgingly and with equal favor among all classes of friends and suitors; when the distinctions of wealth and station were forgotten, and each departing soldier was equally honored as the hero.”

Jackson was a fanatic about duty, and duty dictated punctuality, and he was not, merely for the sake of this romantic war that everyone seemed to want, going to waive his rules.

William Tecumseh Sherman come prominently to mind—to grasp early on just how terrible the suffering caused by the war would be, and just how long it was likely to last.

Jackson’s brilliance was that he understood war. He understood it at some primary, visceral level that escaped almost everyone else. He understood it even before it happened.

He opposed secession. Though he was a slave owner, he held no strident, proslavery views. Indeed, his wife, Anna, wrote that she was “very confident that he would never have fought for the sole object of perpetuating slavery.”

“People who are anxious to bring on war don’t know what they are bargaining for,” he wrote to his nephew.

According to his sister-in-law, Maggie Preston, who was perhaps his closest friend, Jackson also recoiled physically at war’s violence. “His revulsions at scenes of horror, or even descriptions of them,” she wrote, “was almost inconsistent in one who had lived the life of a soldier. He has told me that his first sight of a mangled and swollen corpse on a Mexican battlefield . . . filled him with as much sickening dismay as if he had been a woman.”

Jackson still hadn’t given up. He was ready to die for Virginia and for the South, but he still did not believe God was going to let this happen.

In the end, he chose war because he believed Virginia had no choice and, like most people in the United States of America in the year 1861, Jackson’s first loyalty was to his home state.

The raid was so poorly organized that it looked like a planned martyrdom. Brown never made it out of Harpers Ferry, nor did he even appear to have a plan for escaping, let alone arming hundreds of thousands of slaves. His raiding party managed to kill seven townspeople and wound ten others. Then a group of eighty-six US marines under army colonel Robert E. Lee arrived from Washington, stormed the building where Brown and his men were barricaded, and put a fast and violent end to Brown’s gambit.

Both John Brown and Thomas Jackson were hard, righteous, and uncompromising men, religious warriors in the tradition of Oliver Cromwell, the ardently Christian political and military leader in the English Civil War.

Both believed beyond doubt that God was on their side. Both believed that they were agents of God and that by killing the enemy they were doing His work.

Brown’s words—and his self-possession in the courtroom—changed everything. These were not the words of a madman and a murderer, as Northerners now saw it, but of a principled religious man who insisted that his purpose had not been to incite rebellion but simply to arm slaves for their self-defense.

Jackson was now curiously adrift, without a command. No new orders had awaited him on his arrival. No one in authority had any immediate plans for him. This was despite the fact that, of 1,200 West Point graduates who were fit for military service at the beginning of 1861, only 300 were in the South, and thus in great and immediate demand in a new country that was planning to repel an invader.

The chaos Jackson found at Harpers Ferry was very like the chaos he had found at Richmond, with one important distinction. He was now in command of

same motley assortment of volunteers and militiamen,

Jackson was, moreover, blessed with not one but two exceptional cavalry officers. There was James Ewell Brown Stuart, known as Jeb, a loud, joyous, irrepressible twenty-eight-year-old West Pointer who had spent his previous military career with the mounted rifles and cavalry in the West.

“Yonder stands Jackson like a stone wall,” he said. “Let’s go to his assistance.”16 At the time, his statement, overheard by four witnesses, probably sounded like an inspiring bit of metaphorical language, something to help spur the men into the fight. But Bee’s words would become one of the most famous utterances of the war, noteworthy both because they gave birth to a name and a legend, and because they were among the last words ever spoken by the dashing warrior from South Carolina, one of the battle’s greatest heroes, who at that moment had less than an hour to live. Now the battle

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The people of the Confederacy had fully expected a splendid victory. They had been quite certain that a Southern boy could whip several times his weight in cowardly Yankees, and they had been proven right.

The triumph at Manassas seemed, quite literally, to be a dream come true. Except that it really wasn’t at all. Those dreams of glory had not allowed for the bloodiest day in American history, in which green troops, Federals included, fought and stood fire with an unexpected fury; they had not counted on the sheer destructive power of the weapons and the hideous, disfiguring things they did to young men, the cruel agonies of death they inflicted.

Victory was also tempered by stark military reality: the exhausted, disorganized Confederate army was in no position after the battle to pursue its quarry into Washington to deliver a final blow.

the side effect of placing Jackson’s name, in an equally heroic context, before large numbers of newspaper readers in the South. On July 29 the Richmond Dispatch published the story; on August 15 the Lexington Gazette in Jackson’s hometown ran it. With these notices, public curiosity about Jackson started to grow. It is noteworthy that as the nickname began to attach itself to him, it also attached itself to his brigade. Soon enough, Thomas J. Jackson would be Stonewall to everyone in the South and eventually the North as well.

For the rest of the war and into the annals of American history, they would be called the Stonewall Brigade, the most famous fighting unit of the Confederacy. Jackson

Jackson had graduated from the US Military Academy at West Point on June 30, just in time for the war. He was twenty-two years old, and ranked a respectable seventeenth out of fifty-nine cadets in his class.

No one in his class from West Point—indeed, no one in the entire army in Mexico—had been promoted faster. He was twenty-three years old, and in the small, tightly circumscribed world of the US Army, he was famous.

In the summer of 1861, as citizens in the North and South tried to sort out what had happened on Henry Hill and Chinn Ridge, they began to discuss a new topic: their generals.

The other subject he taught at VMI was something he knew a great deal about, too: artillery. Each day between 2:00 p.m. and 4:00 p.m. he would drill cadets in the transportation, deployment, and firing of mobile field artillery consisting of four six-pounder smoothbores and two twelve-pounder howitzers. In place of horses, underclassmen would pull the field pieces around the drill ground. Most of this was straight mechanical drill.

“At the distance of a few hundred yards, a man might fire at you all day without your finding it out.”1 That’s Ulysses S. Grant, making fun of the old .69-caliber, muzzle-loading, smoothbore musket the US Army used in the Mexican-American War. He was only slightly exaggerating. Though the weapon threw a frighteningly large projectile and could be fired quickly—up to four times a minute—using one was like shooting a marble from a shotgun. It was famously inaccurate at any range above a hundred yards, and often not much good beyond eighty yards.

Civil War commanders stuck to the old close-order formations that Napoleon had used half a century before.

Imagine, then, a 2,500-man brigade, packed into tight battle lines, moving at “quick time,” which meant they would cover eighty-five yards a minute, toward the enemy’s defensive position.

This was the orthodox Civil War “charge.”

Ninety-four percent of all men killed and wounded in the war were hit by bullets. Jackson’s love of the bayonet was an anachronism: less than half of 1 percent of wounds were inflicted by saber or bayonet.

The Union quickly remedied that problem. In 1862 most Federal soldiers were equipped with either Springfield or Enfield rifled muskets. But the Confederacy lagged far behind. Jackson’s valley army fought at Manassas and in the valley campaign with smoothbores, a condition that did not begin to change until he later captured so many Union arms that he was able to partially reoutfit his army.

According to a number of descriptions by ordinary soldiers, their equipment at the beginning of the war was badly outdated. John Worsham, an infantryman who served under Jackson, recalled an abundance of smoothbores, including old modified flintlocks, Mississippi rifles, pistols, and double-barreled shotguns. “Not a half dozen men in the company were armed alike,” he wrote.

Though James Longstreet was a good general and a resolute fighter, he was a prosaic and somewhat colorless human being. Jackson, by contrast—remote, silent, eccentric, and reserved, his hand raised in prayer in the heat of battle—suggested darkness and mystery and magic. Longstreet inspired respect; Jackson, fear and awe.

Then there was Jackson himself, whose astonishing good luck on the battlefield had just run out. He was hit by three bullets. One, a smoothbore round, entered above the base of his right thumb, broke two fingers, and buried itself under the skin on the back of his hand. The other two hit his left arm and were far more destructive. One entered an inch below his elbow and exited just above the wrist. The other hit him three inches below the shoulder and completely shattered the bone.

“I am badly injured, Doctor,” Jackson replied in a calm but feeble voice. “I fear I am dying.” After a pause he went on, “I am glad you have come. I think the wound in my shoulder is still bleeding.”

Shortly after 3:15 p.m. he awoke in a delirium, crying, “A. P. Hill to prepare for action! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly. Tell Major Hawks . . .” Then he went abruptly silent. Soon “a smile of ineffable sweetness” came across his face and he said, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.” Then, without pain or struggle, McGuire wrote, “his spirit passed from the earth to the God who gave it.”

Even before Lee’s official announcement of Jackson’s death, the news was surging through the camps of the Army of Northern Virginia. It did not seem possible that, just as the Confederacy was celebrating its greatest victory—indeed, the high-water mark of its existence—the great warrior was gone.

Zachary Taylor was an authentic war hero, but his passing had more effect on sectional politics than on anything vital to the fate of his country. Washington died at sixty-seven and was buried quietly and with no fanfare in 1799, as was Jefferson (eighty-three) in 1826. John Adams, who died at ninety the same year, drew four thousand to a church in Quincy, Massachusetts. William Henry Harrison, also a war hero, was the first sitting president to die in office and the first to get a state funeral. But it was a quiet, small-scale affair. None of these men died on the battlefield or during a war

...more

It was also overshadowed in history by another, more momentous passing almost exactly two years later: that of President Abraham Lincoln. The similarities between the two are striking, starting with their symbolism. All that wild grief was not just for the two leaders. Their deaths embraced the deaths of all soldiers on battlefields far away; their bodies became the bodies of young men who would never come home; their funerals stood in for the hundreds of thousands of funerals of dead soldiers that would never take place.19 They were vessels into which the vast, pent-up heartache of the

...more

There were other striking similarities. Both men died at the height of their power and achievement, and also at the high-water marks of their respective countries in the Civil War.

Both men were transported back home—another idea fraught with emotional symbolism in a geographically dislocating war—by trains that wound through the countryside while grieving Americans clustered around and threw flowers. The scale, of course, was vastly different. The South did not have the concentrated populations the North did. New York was not the same as Lynchburg. In New York alone seventy-five thousand people followed Lincoln’s cortege. But the ideas and feelings were the same. Both men were Christian heroes who believed that God was with them and against their enemies, and to their

...more

But in the North there was widespread admiration for Jackson, for both his Christian piety and his warrior prowess. Harper’s Weekly described him as “an honorable and conscientious man” who had hesitated to take sides until secession forced his hand.

“I rejoice at Stonewall Jackson’s death as a gain to our cause,” wrote Union brigadier general Gouverneur K. Warren, soon to be a hero of the Battle of Gettysburg, “and yet in my soldier’s heart I cannot but see him as the best soldier of all this war, and grieve at his untimely end.”23

Northern feelings about Jackson were perhaps best summarized by John W. Forney, the prominent editor of the Washington Chronicle. “Stonewall Jackson was a great general, a brave soldier, a noble Christian, and a pure man.

Robert E. Lee would never again be quite so brilliant. After the war he commented only once on what might have happened if Jackson had lived. He was talking about Gettysburg. “Jackson would have held the heights which Ewell took on the first day,” he told his brother. By that he meant that Jackson would have seized the high ground where the Union made its famous defensive stands: Cemetery Ridge, Big and Little Round Tops. There would have been no Pickett’s charge because Jackson would have held that ground before the battle started. It’s all hypothesis. We will never know.

Jackson in the Mexican-American War, 1847: Just out of West Point, the shy young man traveled south to fight in Mexico, where he showed almost reckless bravery in the battles that led to the fall of Mexico City. He was rapidly promoted.

Main Street in Lexington as it looked in the Civil War era. A block away, Jackson founded and ran a successful Sunday school for slaves. Here he made his life before the war as a college professor, investor, farmer, homeowner, husband, and church deacon.